| 6 mins read

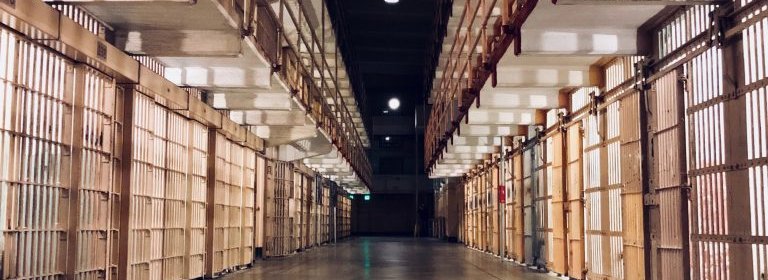

We are in the midst of the latest and perhaps most radical reconfiguration of the penal state in the UK. Such changes are permeating all aspects of the landscape and calling the legitimacy of the ‘system’ into question. From transformations in judicial sentencing policy to the ‘hollowing out’ of probation and the ‘crisis’ of the custodial estate and rehabilitation, recent developments have heralded an unprecedented disruption of policy, practice and political discourse.

Whatever happened to the promises of fresh thinking encapsulated by the coalition government's ‘rehabilitation revolution’? In its place, we have witnessed greater levels of prison overcrowding, mass court closures (including the development of a digital justice platform) and the highly contentious introduction of the private sector into probation services. What impact are these developments having on the initiation, formulation and implementation of penal policy? How can we further our theoretical understandings of what is unfolding?

The past fifty years have seen changes in penal policy from penal welfarism, to offender management, to new forms of network politics. Several important milestones have contributed to current penal controversies.

From principled pragmatism to new penal governance

The postwar climate within which penal policy was designed was one of principled pragmatism and rehabilitative policies. This approach collapsed in the late 1970s, with its demise garnering support from both the political right and left. There had been a growing realisation that purely rehabilitative measures had not substantially reduced the crime rate and that some forms of rehabilitation (under the name of ‘treatment’) were exploitative and inhumane. This ‘vacuum’ was soon plugged by the ‘justice model’ that was set to dominate penal policy in the UK and across the Atlantic during the 1980s and 1990s.

‘Justice’ in this context meant the introduction of more punitive policies designed to appeal to growing public anxieties about the upwards crime trend. Previously focused on ‘reforming the offender’, the new discourse was concerned with the ‘management of risk’. Key elements of the project (competition, contracting‐out, performance management, measurement and evaluation) heralded the beginnings of radical transformations to the penal sphere.

Theoretical conceptions of the state have since moved from the language of new public management to that of new public governance, which views the state as ‘an interaction of multiple stakeholders’. In common with other areas of the public sector, the modern penal state can therefore be characterised as decentralised (administered through arms‐length bodies), fragmented (through more outsourcing, more contracting out and more partnership‐working with private and voluntary providers). Such developments have obvious implications for legitimacy, accountability and risk, particularly pertinent in the penal field.

Coalition penal policy and beyond…

The election of 2010 undoubtedly provided a policy window for those hoping to witness a new direction in penal policy. The first Justice Secretary, Ken Clarke, promised a ‘rehabilitation revolution’. Announcing that fewer young people would be sent to custody and that those with mental health or addiction problems would receive specialist help in the community, this renewed focus on rehabilitation came hand in hand with other, managerialist developments.

To the dismay of reformers, Clarke was removed from office in 2012 and replaced by ‘attack dog’ Chris Grayling, unashamedly punitive in his approach. Clarke's legacy did continue, however, and his early visions formed the basis of the Transforming Rehabilitation agenda, enshrined in the Offender Rehabilitation Act of 2014.

A recipient of one of the biggest budget cuts in government, the Ministry of Justice (and its executive agencies) was subsequently forced to undergo radical restructuring during the period of imposed austerity. The department framed its actions under the banner of ‘Transforming Justice’, but in reality this represented an urgent need to cut costs, streamline provision, and contract out services where possible.

Such fundamental changes resulted in a busy legislative agenda. The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act received royal assent in 2012. More changes came in the form of the Offender Rehabilitation Act of 2014. The legislation contained the measure to contract out to the private sector the management of low and medium level offenders in the community, thus splitting the existing probation service into two.

Continued unrest in our prisons means that the need for fundamental reform remains equally high on the agenda. It remains to be seen, however, whether the government will place the same priority on the prison reform agenda now that we have entered the era of Brexit politics. It may be that the policy window has now closed (for now at least), and that the justice agenda will now be dominated by the politics of terrorism, immigration and a recalibration of human rights. For those who would like to read more on the subject, this Political Quarterly special issue is our collective attempt to make sense of what is going on.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley