Our history

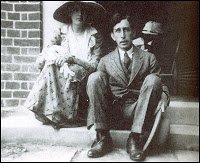

John Maynard Keynes with Kingsley Martin

Beginnings: PQ under Woolf and Robson (1930–1958)

‘I conceived of the idea in 1927 of a serious political review in which political ideas could be discussed at adequate length, and shortly afterwards found that Kingsley Martin had arrived at a similar idea’. So wrote William Robson in 1971, reflecting on the beginnings of The Political Quarterly. In the late 1920s, Robson and Martin were both junior teaching staff at the London School of Economics. Despite some concerns over the viability of such a periodical, the two men managed to marshal an impressive collection of backers (signatories of the journal’s initial prospectus included J. A. Hobson, A. D. Lindsay and G. D. H. Cole) and a pool of funds to allow a three-year trial run of the publication, the bulk of which came from George Bernard Shaw.

The minimum amount considered necessary to ensure a trial run of the Political Quarterly for three years was £2,000, allowing for substantial deficits during this period. Martin, Robson and Woolf persuaded a number of their friends and acquaintances to contribute sums varying from £5 to £150, but the total came to less than half the amount needed. After a series of persuasive letters from Robson, Bernard Shaw was convinced to donate £1,000 to plug the gap. They set up a small committee to take responsibility for launching the quarterly. This consisted of Leonard Woolf, A. M. Carr-Saunders, Harold Laski, J. M. Keynes, T. E. Gregory, Kingsley Martin and William Robson.

Publication began in January 1930, published by Macmillan. Virginia Woolf hand sewed early editions of the journal.

Sidney Webb (with his wife Beatrice, one of the signatories on PQ’s founding prospectus) published an account of ‘What happened in 1931’ in the journal, reflecting on his period as a Cabinet member in the second Labour government.

The first issue of the Political Quarterly stated that:

The function of the Political Quarterly will be to discuss social and political questions from a progressive point of view. It will act as a clearing-house of ideas and a medium of constructive thought. It will not be tied to any party and will publish contributions from persons of various political affiliations. It will be a journal of opinion, not of propaganda. But it has been planned by a group of writers who hold certain general political ideas in common and it will not be a mere collection of unrelated articles…

The year before the financial crisis of 1931 was a difficult moment at which to launch a new periodical. The journal experienced significant losses in 1930, 1931 and 1932. However, it managed to survive, and among those who helped them was Sir Stafford Cripps. In 1933 Robson approached George Bernard Shaw for further funding, but he flatly refused, writing: “Derelict magazines are hard to kill; or rather they are hard to bury… I think it shocking to bleed Cripps personally to keep the wreck afloat”.

A short time after PQ’s founding, Martin was offered the editorship of the New Statesman, a post he would hold for thirty years. Martin resigned as PQ editor in summer 1931, to be replaced by Leonard Woolf. Martin remained a member of the editorial board until his death in 1969 and he took a continuing interest in the paper he helped to found. Other board members included A. M. Carr-Saunders, T. E. Gregory, Harold Laski, Maynard Keynes, Arthur Salter and E. D. Simon. ‘It was, as the names show’, wrote Woolf of the founding board, ‘left wing politically but of irreproachable respectability’. Woolf and Robson remained as joint editors for more than twenty years, excluding the period 1941–45 when Robson was seconded from the LSE—where he completed his undergraduate degree and PhD before being appointed as a lecturer in 1926 and would spend his whole career, retiring in 1962 as professor of public administration—to undertake war work for the Civil Service and Woolf managed the publication alone.

In Robson's ‘Introduction’ to The Political Quarterly in the 30s, he wrote:

After reading this brief account of PQ in the 1930s the reader may ask: ‘What were you trying to do?’ … We were trying to give a wider and deeper understanding of contemporary problems, some of which were being reported in the daily press or debated in parliament at a superficial level. We were also trying to direct attention to questions which were not being discussed at all and which we felt were important or likely to become so. We were trying wherever possible to base those policies on philosophic principles or theories, and also on a firm foundation of expert or specialised knowledge. We were trying to show that many social, economic and political reforms were required in a Britain which had not had a government willing and able to introduce reforms since the Liberal administration of 1906-14. We were trying to show the way to a more just, prosperous and civilised society and to a more peaceful and secure world. And we are still trying.

Leonard and Virginia Woolf

International man of mystery: Tom McKitterick (1958–1966)

Woolf stepped down as editor in 1958 (although he would stay on for some years as Literary Editor), to be replaced by Tom McKitterick. McKitterick had graduated from Cambridge with a degree in classics and history in 1936. In June 1935, while still a student, he travelled to Santander, where he had connections with the Spanish republican movement; he would retain strong links with Spain for the rest of his life, but was unable to return while Franco was in power. McKitterick had an impressive war record, having served as an intelligence officer in the Middle East and the Balkans between 1942 and 1945. He compiled detailed reports into the political makeup and situation of countries in the region, which were sent back to London marked ‘most secret’. He spent his postwar career working for The Economist, specifically its economic research unit, and travelled widely with this role. He had a particular interest in the Caribbean and South America.

McKitterick’s interest in foreign affairs was reflected in his contributions to PQ, where he often commented on economic and political matters in the Middle East. He first wrote for the journal in 1952, when he was also serving on the executive committee of the Fabian Society; he was the author of a number of Fabian pamphlets, including 1951’s ‘Conditions of British Foreign Policy’. He was twice a Labour parliamentary candidate in the 1950s, first against Harold Macmillan in 1951, losing what his family remember as an unusually bitter contest to the future prime minister in Bromley. He was Labour’s candidate in York in 1955, hoping to overturn a Conservative majority of just seventy-seven. The incumbent Conservative, Harry Hylton-Foster, was an old Etonian and a future Speaker of the House. Unfortunately for McKitterick, Hylton-Foster increased his majority to more than a thousand come election night.

McKitterick spent eight years as editor before stepping down; despite publicly citing the demands of his other work, he confessed in a letter to Woolf that his working relationship with Robson had broken down completely, and he left the board upon standing down as editor. He died in 1986. Having written a novel which had gone unpublished, in 1990 the McKitterick Prize was endowed in his name and awarded each year by the Society of Authors to the best first novel by an author over 40. He was replaced at PQ by Bernard Crick—then just 36, and regarded by many, including Robson, as a promising young mind in his field. Crick remains in many ways the totemic figure in the history of the journal.

Totemic figure of the journal: Bernard Crick

‘At times it seemed as though the word “irascible” had been especially invented for Bernard Crick’, recalls former editor Colin Crouch, ‘but he was a big-hearted, generous man; always amusing and witty, the wit ranging from caustic to mischievous.’ But he could also be deadly serious; he even entitled his never-to-be completed history of the journal’s first seven decades, ‘Seventy Serious Years’. He was the faithful keeper of the soul of a number of causes. The Labour Party was one. Another was PQ. He had been co-editor (although their relationship was not always harmonious) with Robson at the London School of Economics, where Bernard had started his career. Guardian of the founders’ legacy, Crick insisted that PQ’s title included the definite article, but would always refer to it familiarly as ‘the mag’. It was a publication he first wrote for in 1957 and was still writing for in 2008, the year of his death.

A third of Crick’s causes was George Orwell—as both a political mentor and as the embodiment of a way of writing about politics that was serious, but accessible. Crick served as Orwell’s political memory in his 1980 biography, written partly, he used to say, to rescue him for the left and from the hands of the CIA, who used Orwell’s discovery of the horrors of Soviet communism to turn him into a Cold War hero. Crick was enormously prolific, but his obituary described the biography as what he considered to be his magnum opus. Orwell’s legacy of a political writing style was further preserved by Crick—both in the way he sustained PQ as an organ that non-specialists could read and, later, through his invention of the Orwell Prize.

Politics, irrespective of party—and the study of it—were also dear to Bernard Crick. His In Defence of Politics (1962) inspired many with an initial interest in the subject and is still a much-read classic sixty years later. His PhD thesis, The American Science of Politics, was a very early critique of how US political science was making the subject jargon-ridden and incomprehensible. This came at least twenty years before rational choice theory and the availability of huge databases, which in the words of Crouch, ‘enabled its practitioners to fulfil their goal of making it as impenetrable and remote from actual politics as economists had made their discipline from the economy’.

In the 1980s, Crick served as an unofficial advisor to Labour leader Neil Kinnock. He and David Blunkett, who had been his student at the University of Sheffield, produced a draft statement of aims and values for the party which was comprehensively squashed by Kinnock’s office in favour of an altogether less interesting statement drafted by Roy Hattersley. Crick was able to realise a dream when Blunkett, as Secretary of State for Education, appointed him in 1997 to prepare a plan for citizenship education in schools. In 1998 he chaired a committee tasked with drawing up a test of minimum competence in English language and British culture which immigrants to the UK would be asked to take before they could be granted permanent residence. He continued to serve as an advisor for the Labour government on integration and naturalisation issues until 2005. The Labour government implemented the citizenship education report and Crick received a knighthood in 2002 for his work (although, some obituaries noted, what he really hankered for was a peerage). Congratulating him, Tony Blair said: ‘But why do you call it citizenship and not volunteering?’ However, under subsequent Conservative governments, the citizenship scheme has been squeezed to the margins considerably: ‘One member of Crick’s committee of my acquaintance regards the citizenship tests as a mistake and a great embarrassment’, comments current PQ co-editor, Deborah Mabbett, ‘and I suspect Crick would agree if he was around now’.

Academic, MP, and champion of devolution: John Mackintosh

Crick had a number of co-editors, the first being John Mackintosh, who took over in 1975. Mackintosh became the first of—at current count—three editors of PQ who had also served as Labour MPs. Born in India and educated in Edinburgh and Oxford, he worked at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria (where he met his second wife Una Maclean, a medical doctor and prodigious researcher) before becoming a professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde and later professor and chair of politics at the University of Edinburgh. He was elected—on his third run for Parliament—to represent Berwick and East Lothian in 1966. He lost his seat in the first of 1974’s two general elections, only to gain it back eight months later. His main parliamentary interests were in the issues of devolution and Scottish representation and his academic work reflected this interest, notably his 1968 book, The Devolution of Power. However, his best-known book was probably The British Cabinet, a highly influential early account of the growth of prime ministerial power and demise of cabinet government. Among his other concerns as a politician was parliamentary reform, and he served as chair of the Hansard Society.

Mackintosh died in 1978, aged just 48, and the Glasgow Herald wrote that he was among those politicians who ‘never seem to achieve the ministerial posts for which their manifest talents obviously suit them’. Nonetheless, he left a powerful imprint on the post-Crosland generation of Labour revisionists, many of whom would go on to join the Social Democratic Party (SDP), perhaps most notably future PQ editor, David Marquand. Journalist, David Watt, took over Mackintosh’s post as PQ co-editor upon his death and the thrice-divorced Crick later settled in Edinburgh with Mackintosh’s widow, Una.

Publishing in the pre-internet era

PQ has been published by several different companies. Between 1930 and c.1945 it was published by Macmillan. The future prime minister, Harold Macmillan, then a junior in his family firm, was approached by PQ’s founders for advice before the journal was set up. Between c. 1945 to 1957 it moved to Turnstile Publishers, followed by Stevens between 1957 to 1962, before moving to Thomas Nelson, on behalf of Thomson publishers, between 1962/3 and 1985. From 1985 onwards PQ joined Blackwell, which later became Wiley-Blackwell and then Wiley, where it remains.

Blackwell was based in the Oxford publishing district, one of the most thriving ‘industrial districts’ in the UK, populated by several small publishing firms, many academic authors, and a mass of typesetters and copy editors, mainly women working from home and all within a short distance from each other. ‘To appreciate the value of this you have to carry out the increasingly difficult exercise of imagining a world without the internet’, former PQ editor, Colin Crouch, comments. In this world, authors sent articles to journals through the post to editors, who would send back comments by post, and in the same way receive revised versions. These would be posted to the copyeditor, who would post back her work to the editors, who would post to the publishers, who would post to the typesetters, and then back to the publishers. ‘In my time as Assistant Editor I would actually deliver the final copy … by hand in person, and later pick up the proofs in the same way’ comments Stephen Ball. A philosopher by training, Ball was Senior Lecturer in Publishing at Oxford Brookes University, specialising in editorial practice and academic publishing and was with PQ for some fifteen years in the early 2000s. The proofs would then be posted to the printers, which were located in the same city (but by the 1980s were increasingly based in India). ‘Only geographical propinquity and the use of bicycles could short-circuit much of this, and those we had’, says Crouch. At that time, ‘Blackwell were located near the city centre, not far from my college; a director at Blackwell, René Olivieri, lived in my road; and I was delighted to discover that the firm’s preferred typesetter was Anne Joshua.’

Joshua organised a group of women who typed up theses and articles for academics. By the end of the 1970s she had spotted the potential of the emerging new technology and installed a battery of computing equipment in the basement of her home, opposite Crouch’s residence. ‘A few years earlier I had included a fairly simple equation in a chapter I was contributing to a book’, Crouch remembers. ‘The publishers (not Blackwell) told me that this was technically very difficult (although it would be very simple today). If I insisted, I would have to stump up personally the £300—that is, a 1970s £300—that it would cost. That evening I went across to Anne and she turned my equation into usable form for a typesetter while I waited, charging me £30’.

After that, Joshua became PQ’s typesetter. Over the coming years publishers, including OUP, would approach the journal and ask if they would consider switching from Blackwell to them. ‘I would always ask: “Will you keep Anne Joshua as the typesetter, or will you take the work to India?”’ Crouch recounts. ‘“To India”, they would always reply. So, PQ stayed with Blackwell. Since then, Blackwell has moved to the outskirts of Oxford, been taken over by the US publishing giant, Wiley, and even their name has now disappeared. Anne Joshua passed away, and PQ is typeset (very well) in India.’

The other key person in those years was Audrey Coppard. As Company Secretary and copy editor, Audrey was ‘the real heart of PQ’, according to Crouch. She had been Crick’s secretary when he was professor of politics at Birkbeck, had jointly written a book on Orwell with him, but carried on working for PQ after he had retired to live in Edinburgh.

The 1980s: Klein, Watt, Crouch, Marquand and the SDP rift

The early 1980s saw the British left riven by the break away from the Labour Party of the short-lived SDP. The board of PQ was a microcosm of that rift: a majority of its members, mainly academics and journalists of the first postwar generation, had sided with the new party. Bernard Crick, the chair of the Editorial Board, was a fierce Labour tribalist and suspected an attempt to take PQ over and turn it into an SDP organ—something the fledgling party would have found very useful. When a vacancy appeared on the board in 1982, he therefore asked Colin Crouch, a sociologist then at the LSE and, crucially, a Labour loyalist, to be candidate for it. Crouch says of the time: ‘Hardly anybody knew who or what I was, except for Shirley Williams, a leading SDP founder, with whom I was on good terms. So, I was elected with no trouble’.

In the early 1980s the journal’s editors, Rudolf Klein and David Watt, were both of the SDP persuasion. Watt, born in 1932, had had an impressive career as a journalist, having started out at The Spectator, spent a period as the Financial Times’s Washington correspondent and was, by the 1980s, a weekly columnist for the Times. A long-time friend of David Owen, another leading SDP founder, Watt was enthusiastic about the European Community and a spirited critic of Harold Wilson, so his defection from Labour to the SDP was, when the time came, all but inevitable. He argued that while he had stayed in the same place, Labour had moved to the left on a variety of issues, including South Africa. He tragically died after an accident in 1987. Klein was born in Prague in 1930, from where he fled with his parents to Britain in 1939. After studying history at Merton College, Oxford, he too became a journalist, working for the London Evening Standard and as a leader writer for The Observer—a job previously done by his PQ forebear, Kingsley Martin. His work largely focussed on the NHS and the welfare state, and in the late 1970s he transitioned to academia, taking up a post at the University of Bath in 1977.

Bernard Crick had Crouch elected to succeed him upon Watt’s retirement in the interests of balance. Two years later Klein also retired as editor and, Crouch remembers, ‘the board insisted that my new colleague should be from the SDP’ and David Marquand was elected. Marquand, at that time professor of politics at Salford, had been a Labour MP and was another founder member of the SDP. In spite of their ideological differences, however, Crouch and Marquand shared a vision of reconciling the values that Labour and SDP stood for, and wrote several comment columns exploring that possibility. Marquand is among PQ’s best known former editors. Born in 1934, he stood for Parliament, first unsuccessfully, in 1964, before being elected as Labour MP for Ashfield, Nottinghamshire, in 1966. As a politician, he was heavily associated with SDP leader Roy Jenkins. In 1977 he resigned his seat in Westminster to follow Jenkins to Europe as an advisor and he left Labour for the SDP at its founding in 1981. Marquand is better known for his writing than his political career and it was this that led him to PQ. In 1979, following Labour’s election defeat, he wrote the influential article ‘Inquest on a movement’ in the magazine Encounter, which argues the centrality of the role of the radical intelligentsia in Labour’s vision and success; in this, he echoes arguments made by William Robson.

His best-known work remains 1991’s The Progressive Dilemma, in which he argues that the tragedy of British politics in the twentieth century is the split in the forces of progressivism—into Labour and Liberal—and that without this split, the country could have enjoyed a progressive rather than Conservative dominated political century. He served as editor between 1987 and 1997, a period which started with Marquand at the centre of negotiations for the merger between the Liberals and SDP which formed the Liberal Democrats, and ended with him a Labour Party member, playing a somewhat ambivalent role in the party’s modernisation under Blair.

The 1990s: Wright, Gamble, Cornford and New Labour

In 1993, Bernard Crick retired as chair of the Editorial Board to become Literary Editor, thus changing places with James Cornford. Cornford chaired the PQ Editorial Board in the same genial, tolerant, but business-like manner that he conducted the rest of his life. An alumnus of Dartington Hall school, whose father had been killed fighting in the Spanish civil war, Cornford was born in 1935. In his early career, after an undergraduate degree at Cambridge and followed by a never-completed doctorate, he had been an academic prodigy, appointed to the chair in politics at the University of Edinburgh when only 33. His appointment owed much to the influence of a Glasgow professor, W.J.M. (Bill) Mackenzie. The 1960s were a decade of university expansion, not least in the social sciences, and two especially influential people, brought in as outside advisers on Chairs in Politics, were Bill Mackenzie (for many years head of the Department of Government at Manchester before moving to Glasgow University in 1966) and D.N. (Norman) Chester, the Warden of Nuffield. It was hardly a coincidence that a lot of the new Politics appointments went to people who taught at Manchester or to former graduate students of Nuffield. James Cornford, though, was neither. Mackenzie did not hesitate to advance the careers of bright young people, and James clearly fell into that category. Bill also liked the famous Cornford Cambridge background and the radical-romantic Spanish Civil War connection. Mackenzie was, however, very keen indeed on academics publishing (at a time when it was not quite as obligatory for university teachers as it is now) and so probably thought that James’s subsequent move to the world of foundations and policy-making was all to the good.

Cornford’s own explanation for giving up his Edinburgh Chair in 1976 was dissatisfaction with what he viewed as the triviality of academic life. He devoted the rest of his life to a variety of roles (including director of the Nuffield Foundation, founding director of the policy unit at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and chairman of the Freedom of Information campaign) in which he promoted causes and helped others develop their careers. Between 1989 and 1994 Cornford was the first director of the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), where he shaped a research agenda helpful to the rapidly changing Labour Party, including overseeing a significant project on a subject long of interest to those who edited, wrote for and worked on PQ—constitutional reform. Rarely adopting a public stance himself, Cornford preferred to provide a platform from which others, including IPPR alumni like David Miliband and Patricia Hewitt, could launch their political careers. He briefly entered government as an advisor to David Clark MP, with whom he worked on a Freedom of Information Bill for the 1997 government. Clark and Cornford considered the resulting Freedom of Information Act (2000) to have been excessively diluted by the government; Clark resigned as a minister and Cornford went with him into unemployment. ‘Put not your trust in princes’, he wrote to his PQ colleagues, quoting Psalm 146.

During the years running up to 1993, relations between Bernard Crick and another member of the board were becoming cantankerous and spoiling meetings. Cornford convinced each of them that the other would retire from the board if he did. They agreed, Bernard, winking, saying ‘Ah; my tryst with Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls!’. They both left the board, but Bernard became PQ’s Literary Editor (see above). Sherlock Holmes returned from the Reichenbach Falls.

Whilst still a member of the board, Crick, assisted by Colin Crouch, developed and raised funds for the Orwell Prize, which he had set up in 1993 with the royalties from his Orwell biography. Its aim has been to reward writers who fulfil Orwell’s ambition of turning political writing into an art and it quickly established a high reputation for integrity.

Later, at the 1999 PQ AGM, a rule was introduced that all the editors (including Literary Editor, and Reports and Surveys Editor) must also be on the board. Cornford retired as chair in 1999; his political optimism had been damaged by his Freedom of Information Bill experience and he was happier planting trees for the future at his home in East Anglia. Crouch succeeded him as chair, ‘with Bernard’s Crick’s injunction ringing in my ears: “Never interfere with the work of the editors! Your job is just to sort out any problems and oversee the election of new editors and board members.”’ It was a rule Crick had followed faithfully himself. Occasionally, Marquand and Crouch, when editors, would receive a postcard from him complaining that an article in the latest issue contained more than five footnotes; Orwell never used footnotes. ‘But Crick never dreamt of doing anything other than muttering about it’, remembers Crouch.

Tony Wright was first elected to Parliament as the Labour MP for Cannock and Burntwood in 1992, having previously taught politics at the University of Birmingham. He replaced Crouch to become PQ’s co-editor in 1995, serving until 2016—the longest term of any editor since Robson and Woolf. He stayed in Parliament until 2010 and is now attached to UCL’s Constitution Unit. A self-identified ‘Blairite’, writing in 2000: ‘I became a Blairite (even before Blair, I like to think) because I wanted the centre left to become the dominant force in British society, as I believed was possible if Labour was reformed and modernised’. He was nonetheless often critical of the Labour leader and leadership and rebelled over the war in Iraq. Like John Mackintosh, he took an interest in parliamentary reform and constitutional issues, chairing the Reform of the House of Commons Committee, which is now generally known as the Wright Committee, in the wake of the expenses scandal.

Wright’s first co-editor was the influential political economist, Andrew Gamble, who took up the post in 1997 and, with Wright, guided PQ through the New Labour years, retiring in 2012. Andrew Gamble, then professor of politics at Sheffield, later professor of politics at Cambridge, was appointed co-editor with Tony Wright when David Marquand retired.

During the 1990s Audrey Coppard appointed Gillian Somerscales (then Gillian Bromley) as Editorial Assistant, later to be renamed Assistant Editor. Gillian created the first formal and detailed style sheet for PQ but left in the early 2000s, to be replaced by Stephen Ball (though Audrey retained the Company Secretary role until she retired herself, then handing it over to him). He retained both roles until he stepped down in 2014. Gillian Somerscales died aged 64 in June 2023, cruelly struck down by motor neurone disease.

PQ in the twenty-first century

Bernard Crick died in 2008, aged 78. A few months earlier, Colin Crouch had visited him in Edinburgh: ‘We both knew what cancer was doing to him, but his wit and mischief were undimmed.’ Cornford also succumbed to cancer three years later, aged 75.

As for Crouch, he claims ‘My achievements as chair were modest … I moved the AGM away from the male-only Savile Club (they had enabled us to have our female members present by accommodating us in an outer room), and took ant’s steps towards diluting the massive dominance of aging white males among the board’s membership. The board was no longer riven by political disputes, and representational issues of this demographic kind had become the main need when appointing new board members.’ Bernard Crick and James Cornford had already recruited younger board members, several associated with the New Labour think tanks, which made for more exhilarating meetings in and around 1997.

Andrew Gamble recalls that at Tony Wright’s invitation the editorial team used to hold its meetings in Portcullis House:

They were always lively affairs which ranged far beyond routine editorial business … When I became joint editor of Political Quarterly with Tony Wright in 1997 the New Labour period was just beginning following Labour’s landslide victory … Labour’s ascendancy coincided with an era of increasing globalisation and international cooperation, marked by renewed western prosperity, the rapid rise of China and India and the expansion of the European Union which followed the end of the cold war. In retrospect this time was a high-water mark for progressive politics, not just in the UK but across Europe. There was a great ferment of ideas on the Left in the 1990s which New Labour drew on and encouraged. They included the work of thinktanks like IPPR under James Cornford and Will Hutton’s The State We’re In. There was a mood of optimism and confidence which all helped to deliver a steady stream of lively content to Political Quarterly.

The old disputes between Labour and the SDP were no more. With Labour in government focus shifted from ideological disputes to how well Labour was doing and what it should be doing differently to deliver progressive policies. We covered the highs and lows of New Labour, and made space for all views on what turned out to be Labour’s longest serving government.

Wright and Gamble’s highly successful joint editorship was also to be a record breaker, lasting twelve years. Meanwhile, as the PQ editorial team grew, Donald Sassoon, a historian of social democracy, became Literary Editor in 2000, and media historian (now official historian of the BBC), Jean Seaton, came in as Reports and Surveys Editor in the same year, taking over from Carey Oppenheim. Along with Stephen Ball, ‘[a]ll three made a major contribution to the continuing success of the journal’, remembers Gamble. As well as her contribution as Reports and Surveys Editor, Seaton also made a major contribution to the Orwell Prize, which she took over in 2006 after Crouch and Crick had stood down. Although the prize had established a reputation for integrity, it had low monetary value and the PQ could not afford much marketing. Under Seaton’s directorship it went from strength to strength, attracting far more funding, achieving great publicity and increasing its range of prizes.

After Gamble’s retirement in 2012, Michael Jacobs, the former General Secretary of the Fabian Society, stepped in as editor for two years—he remains on the editorial board. Jacobs was also one of four sometime editors of PQ who, in 2003, signed the founding statement of the thinktank Compass (the others being Crouch, Gamble and Marquand), then aligned to the Labour Party’s soft left. It has now distanced itself from Labour, but continues to champion a somewhat eccentric left politics with a heavy emphasis on electoral reform and overcoming the ‘progressive dilemma’.

PQ and the digital revolution

Whilst the long editorship team of Wright and Gamble provided one kind of stability, PQ was part of an enormous change in the publishing process.

Publishing in the era before the internet could be rather eventful. Crouch remembers that a very distinguished economist had agreed to write an article for a special issue (which would then be based around his contribution) and had wanted to include a diagram. Blackwell asked if they could have the draft of the diagram, to prepare it well in advance. ‘Our author replied that his department had this extraordinary diagram-producing machine that would be superior to anything Blackwell would have, and he would see to the diagram himself”, says Crouch. Blackwell were still worried and asked for a sample. Some days later it arrived in the post. It was the faintest diagram any of the editorial staff had ever seen. ‘When we all remonstrated, our contributor replied that he did not have a good stylus available at the present time, but would have a superb one when the final version of the article was sent’. Unfortunately, the final version came in the post, long after the deadline, and the diagram was just as faint as before. Blackwell had to do it themselves after all. That issue of PQ appeared after the one that should have followed it. These days technology has left problems like these firmly in the past.

Indeed, the internet has been a watershed for publishing of all kinds. The way PQ operated in 1990 had more in common with how it had been in 1930 than what it was to be like in 2000. ‘I had long wanted to see PQ as a journal that would be the centre of a community of activities, not just a quarterly publishing event’, says Crouch. ‘But I lacked the imagination to see that the internet revolution could achieve exactly that. This had to wait for my successor, Joni Lovenduski’, who became chair of the PQ board in 2010. Now Professor Emerita of Politics at Birkbeck, ‘Joni taking over as chair of the board was a huge milestone for the journal’, remarks Ben Jackson. She was behind the attempt, as Jackson points out, ‘to take advantage of a growing online readership to expand PQ’s reach, for example, by creating a blog and using social media to attract more readers to our journal articles (for which we are greatly indebted to our former Blog Editor, David Sanders, and our Digital Editor, Anya Pearson, who have made all that happen).’

PQ today

The current editors of PQ are Ben Jackson and Deborah Mabbett. Mabbett, a professor of public policy at Birkbeck whose work focusses on comparative political economy and social policy, often in the European Union, joined PQ in 2014, becoming its first woman editor. She reflects that:

Being the first woman editor does not feel like a big deal, as there have been influential women involved in the journal from its inception. But there has been a clear if gradual change in style from the olden days when men of standing could pontificate in comfort, knowing that their authority was taken for granted. The contemporary journal seeks to promote informed debate and it ranges widely in its search for contributors.

Jackson is a professor of modern history at Oxford and a former editor of the journal Renewal. He joined PQ in 2016, replacing Tony Wright and says he feels ‘very fortunate’ to edit the journal: ‘I had long been an admirer of the journal and its distinctive mission of publishing material that is both intellectually rigorous and accessible to a non-specialist audience. I also feel a lot of sympathy for Political Quarterly’s progressive political tradition.’ Jackson says that 2016 and the period after

turned out to be an extraordinarily interesting time to be editing a journal that was trying to make sense of what was happening to politics in Britain and around the world. Throughout those years we have sought to go beyond media headlines and to dig deeper into the seismic political changes of our times. We provide a platform for academics and other commentators who have crucial insights into contemporary politics but who need space to explain their thoughts in depth rather than in the briefer op-ed format.

Since the mid-2010s, PQ has scrapped the practice of publishing a book each year and instead offers more special issues and sections alongside individual articles. In 2020 a new post of Special Sections and Issues Editor was created and Anna Killick was appointed. After an eventful early career as a parliamentary assistant and campaigns manager Anna opted for a quieter life teaching history and politics to A-level students, taking time out in 2015 to complete her PhD at University of Southampton on how people understand the economy. Her own writing in PQ shows that limited knowledge of economic terminology notwithstanding, the public understands it pretty well.

Alongside the creation of new editors, Joni Lovenduski has overseen the expansion and professionalisation of the management team. By 2020 Emma Anderson, who was appointed as Administrator in 2008 was given the title Managing Editor in recognition of her work. She was joined by Clare Dekker who became Company Secretary in 2014, later combining this with the role of Assistant Editor. Along with other members of PQ’s Steering Group (comprised of all editors, the chair and other co-opted members, which meets several times a year to discuss editorial and management matters), they developed the journals services to authors and editors and managed its transition into modern journal production, including the careful development of its investment strategy, maintaining relationships with Wiley staff and paying close attention to changes in the journal publishing world—a world that is becoming more challenging with the transition to open access.

Meanwhile, the process for appointing PQ editors has evolved to become a much more open application process, quite different from its tales of editorial succession from the past. Also changed is the character of the board, as Crouch notes when remembering the PQ annual dinners of the early 1980s, that

seemed even at the time to have belonged to an age before their own: a group of highly intelligent, mainly male persons who remembered the war and the postwar Labour government, sipping their post-prandial drinks and wreathed in cigar smoke as they mulled over an inhospitable political world. Today’s dinners take place in an informal atmosphere; less is drunk; nothing is smoked; but we are just as intelligent, and the world we mull over, at least at this time of writing, is again inhospitable.

PQ and the future

As this history is compiled, PQ faces a challenging future. The financial model of open access publishing does not favour publications which are not primarily research based and there may be some difficult choices ahead if PQ is to retain its unique character—and do that it must.

Wyn Grant, current Reports and Surveys Editor, comments:

PQ provides an opportunity which no other journal does in the same way for academic and non-academic experts to write in an accessible and digestible way about topical issues and hence contribute to public policy debates. The battle about ideas and policy is becoming more, not less contested, and needs an underpinning of rational, evidence-based discussion of the kind that PQ offers.

As Ben Jackson noted in relation to the achievements of recent years, ‘We hope to build on all this in the future—PQ’s work remains as important as ever as we try to understand tempestuous political times.’

Note

This is the first attempt to produce a history of The Political Quarterly up to the twenty-first century. It was initially compiled by Anya Pearson and Morgan Jones and then revised by members of the Steering Group and Archie Brown. The sources are PQ documents, including previous accounts of our history, press sources and interviews with current and former editors and others who have been closely involved with PQ over the years. There is certainly more to add and should be seen as a work in progress. We therefore welcome comments and suggestions for improvement. Please send these to Emma Anderson via our contact form.

Further Reading

W. Robson, ‘Introduction’ to The Political Quarterly in the 30s, London, Allen Lane, 1971

S. Ball, ed., Defending Politics: Bernard Crick at the Political Quarterly, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell/The Political Quarterly, 2014.

L. Woolf, Downhill all the way: An autobiography of the years 1919-1939, 1967.

“Leonard Woolf at the Political Quarterly”. The Political Quarterly, 2014.

A. Gamble and T. Wright,The Progressive Tradition: Eighty Years of The Political Quarterly, 2011.