| 7 mins read

The United Kingdom's asylum system for assessing and managing the processing of claims for international protection is widely perceived as fundamentally broken. For some its dysfunction lies in the numbers claiming asylum and the absence of control over their entry. For others the problems centre on the danger and dehumanisation that asylum seekers endure to reach the United Kingdom. All can agree that the system is costing far too much due to the need to accommodate the very considerable number of asylum seekers awaiting a decision.

The linked issues of delay and cost have now been substantially addressed. But there are new problems looming, which all revolve around dealing with the pathway to either integration or departure.

Lots of newly recognised refugees, lots of appeals, few removals

What happens next to those who are granted asylum? Newly recognised refugees will sometimes have been waiting years for a decision. During that time, they are generally prohibited from working or studying, and live on destitution-level support. They then have 28 days’ notice between receiving proof of their new immigration status and being evicted, which means they have a very short space of time to find a job, get paid some money and find accommodation. Unsurprisingly, many become homeless.

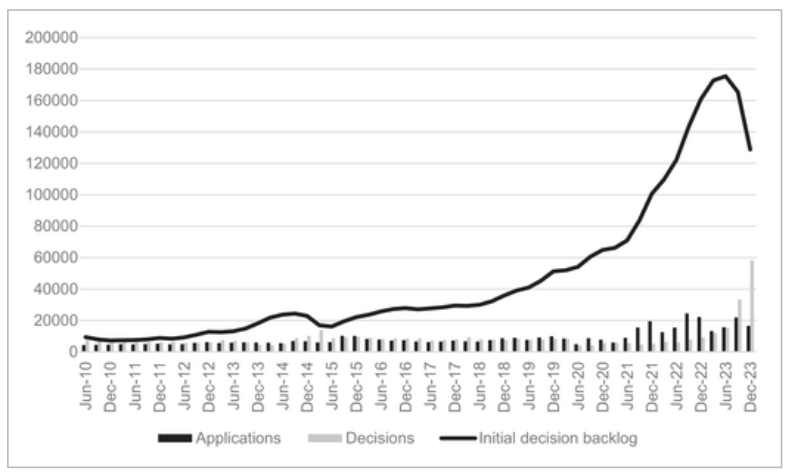

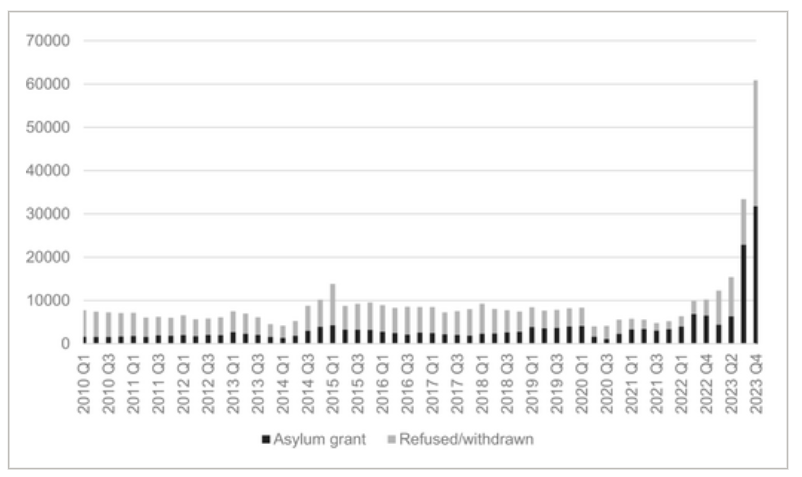

A total of 25,000 initial applications for asylum were rejected over the course of 2023. Many of these rejected asylum seekers will lodge appeals. Only 8,000 appeals were processed the previous year, so any increase in the number of asylum refusals presents significant challenges for the tribunal system and the Ministry of Justice. It is a situation that is likely to get worse because the percentage of asylum decisions which are refused is expected to increase now that many strong cases have been fast-tracked and decided. The initial decision backlog is shrinking. But the appeal backlog is growing.

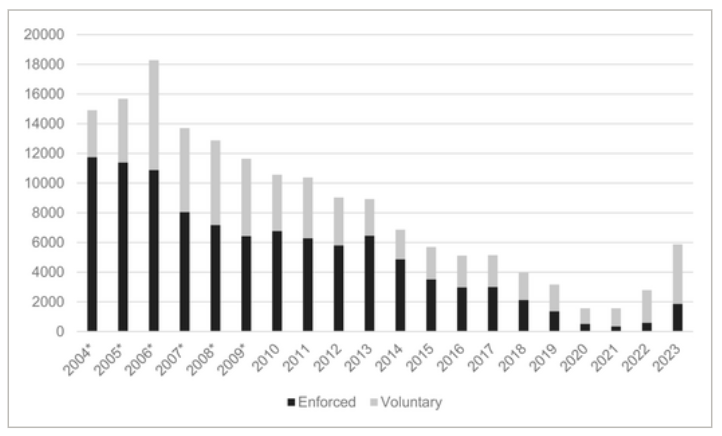

There are two potential outcomes from a refused asylum claim. One is that the failed asylum seeker departs from the country. This departure might be voluntary or involuntary. This is the logical outcome of conducting an expensive asylum determination process. Yet the long-term trend looks a lot like diminished state capacity to enforce or encourage departure. In total, there have been just over 100,000 asylum refusals and withdrawals in the last five years. In the same period there have been 15,000 enforced and voluntary asylum returns. The other possibility is that the person remains in the country without permission. In reality, this is overwhelmingly the standard outcome for failed asylum seekers.

Can the asylum system be repaired?

The United Kingdom’s asylum system is indeed broken. It is, to a very significant extent, Priti Patel who broke it. It was on her watch that small boat crossings soared and so did the asylum backlog. Politically driven schemes like the noise around marine pushbacks and Rwanda, and the degree of departmental energy funnelled into unworkable legislation have made the situation worse.

Figure 1: Asylum applications, decisions and backlog

Figure 2: Number and type of initial asylum decisions

Figure 3: Returns of former asylum seekers. Source: Home Office, immigration statistics year to December 2023, table Ret_05.

The good news for the next Home Secretary is that the asylum backlog is finally coming down. This allows some breathing space. With recovery underway, ministers and managers need to think about prioritising resources.

Recent administrative changes show that positive asylum decisions can be made much faster than in the past. After all, it is not that hard to grant asylum to an Afghan, Eritrean, Sudanese or Syrian given they have a 98% grant rate or more. All officials needed to do was establish nationality, conduct security checks, and issue the grant letter. Banned by ministers from consulting NGOs, the Home Office made entirely avoidable mistakes by issuing long, complex forms only in English and failing to fund any help to fill them in.

Allowing asylum seekers to work after six months waiting for a decision would mean far fewer becoming homeless when they are granted asylum. A support and welcome package for newly recognised refugees should be introduced, which would save money in the long run.

More resources urgently need to be channelled into asylum appeals and legal aid. The appeal success rate remains very high, suggesting that many unnecessary appeals are being lodged. Proper, realistic reviews of pending cases might reduce the appeals backlog and save considerable time and money. Monitoring of officials who wrongly refuse applications or reject an appeal review should be introduced.

Unless a government is willing to build large and expensive prison camps, the number of detention spaces is never likely to be sufficient to remove all those the government in theory wishes to remove. Effectively all it is being used for is to punish a small sample of a wider class of person. If detention is to be used on a more rational basis, the issues are around how Home Office resources are organised, what groups are targeted for removal and what safeguards are used to prevent discrimination, abuse, and the selection of ‘soft’ targets.

The voluntary departure scheme also needs reviewing. A targeted or earned regulation process would recognise the reality of the situation. For example, a form of tolerated status enabling failed asylum seekers who cannot be removed to work and earn their way to regularisation could be introduced, as currently operates in Germany.

The ban on the right to work, the destitution-level support offered instead, the squalid accommodation and camps and the highly bureaucratic, faceless asylum process all absorb vast Home Office resources. Deterrent policies, which belong to a bygone age, deter no-one. They merely serve to punish refugees who will ultimately get to stay in the United Kingdom in the long term. It is in their interests and ours to help them integrate as soon as possible rather than first forcing them into a demeaning purgatory.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley