| 7 mins read

The net zero transition requires rapid decarbonisation. The transport system, our biggest carbon emitter, needs a 72 per cent emission reduction by 2037, while buildings are targeted for a 56 per cent cut. Both are highly visible to consumers in their everyday lives, while others like power generation are further from the public gaze. Any serious attempt to tackle climate change and meet the 1.5C targets set by the Paris accords must transform all systems.

It is notable that personal transport and housing have been the focus of populist backlash crusades. The Conservative government’s approach is geared to producer-dominated systems. Its lesser effectiveness for the demand-influenced systems of housing, food and transport was pointed out by the Climate Change Committee. The power to ensure that all systems are transformed appears to lie more in the broader terrain of politics rather than the specialised domain of climate policy.

Contrasting pathways of power generation and home energy use

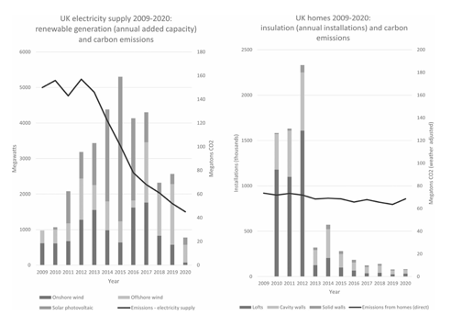

The significance of transition politics is illustrated by electricity generation and housing between 2009 and 2020. One transition pathway is the installation of renewable energy capacity to reduce emissions from electricity generation. This was a greater success than expected. Emissions reduction exceeded the target by more than one third and solar PV capacity installed was triple the target. The home insulation pathway, meanwhile, was a failure. Emissions reduction was only one third of the target, reflecting the far lower level of installations than anticipated. These are shown in the figures below.

The contrasting stories reveal the importance of different configurations of policy, social actors and technology. It is clear that the claimed concern by government to avoid ‘significant costs for working people’ does not explain the difference. Home insulation offers greater cost savings for the consumer than any other pathway, yet this failed. For insulation, reshaping the system for a public purpose was seen as far too awkward territory. Refuge was sought in a flawed ‘market’ of private finance and individual consumers. A neighbourhood approach, needing local authorities with significant financial capacity to support poorer householders and tenants, was ideologically suspect, even when recommended by the Committee on Climate Change in its 2013 report.

Making transition pathways happen: a transition policy framework on housing

The contrasting cases show that the new terrain of climate politics is becoming more about the actions to make specific transition pathways happen than a general debate over targets. While transition in energy production is key, it needs to be accompanied by transitions in energy use in housing, transport and food. Buildings and homes are responsible for a major share of carbon dioxide emissions, with the use of buildings accounting for 27 per cent of global energy related greenhouse gas emissions in 2021. Heat for buildings causes 23 per cent of Britain’s greenhouse gas emissions and housing alone causes 17 per cent of total emissions.

Improving energy inefficiency of many homes will be huge. The UK has the draughtiest housing stock in Europe. Of its 28 million homes, 17 million (60 per cent) are below the minimum recognised standard for measuring energy efficiency. Insulating solid walls remains the key problem: 40 per cent of the total housing stock has walls classified as poor or worse efficiency. In comparison, 21 per cent of homes have roofs at the same standard and 9 per cent of households live with poorly graded windows. Close to 8 million homes with poor walls require upgrading in England alone if all homes are to reach minimum efficiency by 2035. Walls are expensive to insulate, the work is messy and often necessitates internal redecoration—at an average of £8,000 per property. The 28 million gas boilers make the challenge even more immense.

UK experience has shown that good policy making can make a difference. The decade up to 2012 saw significant progress with loft and cavity wall insulation, with a peak of 1.6 million households insulated. Yet, for the Conservative government this has been a missed decade. Both Greg Barker’s Green New Deal in 2012 and Rishi Sunak’s Green Homes Grant scheme in 2020 flopped badly. David Cameron’s austerity programme and his populist call to remove the ‘green crap’ resulted in the dramatic fall in insulation programmes after 2012. Whilst Labour has promised it would insulate 19 million homes, details remain scant. With a worsening financial outlook, Starmer announced a retreat from Labour’s £28 billion per year green plan—particularly its warmer homes programme.

A new model for transition politics

Successful low carbon transformation requires new models of local policy intervention. The sheer scale means recognising its core local dimension that demands neighbourhood schemes are developed so entire streets are renovated and decarbonised together. The key elements of a strategic, decentralised model would include things like a national infrastructure mission for buildings and home energy efficiency, with funds available to protect those on low incomes spending the greatest share on energy. Obligatory local energy action plans to indicate areas for priority action, alongside training tens of thousands of professionals and tradespeople to install insulation and other retrofitting measures, would be among further measures needed. Encouraging new partnerships for local authorities and public institutions, like that between the City of London Corporation and Voltalia to provide £40 million worth of from a solar plant in Dorset, will need government support. There are numerous other policies which the government would need to pursue to make the transition pathway happen.

This type of strategic transition thinking offers a rare opportunity to renew the nation’s housing stock, establish warm, more comfortable homes with lower running costs and create hundreds of thousands of good jobs. It’s a programme that would contribute enormously to a serious levelling up agenda. Are the UK’s political leaders up to the challenge?

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley