| 8 mins read

British politics is currently going through a particularly vibrant era of inquiries. In 2018, an Institute for Government report found that sixty-nine public inquiries were launched between 1990 and 2017, compared with a mere nineteen in the previous thirty years. Since 2018, British politics has to some extent been defined by inquiries.

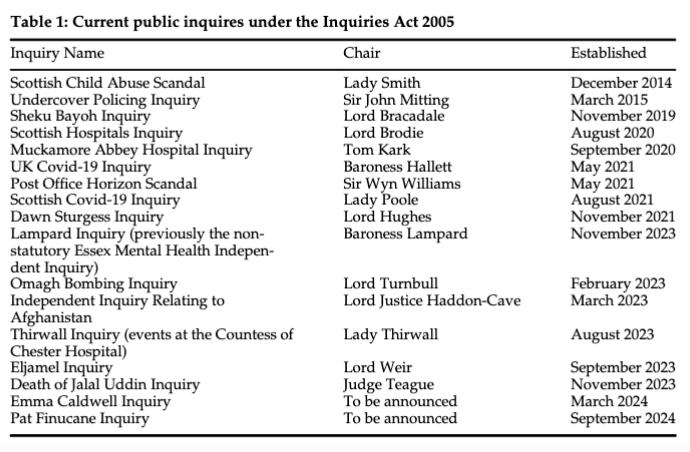

Recently published inquiries include the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse; the Manchester Arena Inquiry; and the Brook House Inquiry. Current inquiries are exploring issues as diverse as the Scottish child abuse scandal, undercover policing, and the UK's response to Covid-19. Never in British political history have so many public inquiries been running concurrently.

Table 1. Current public inquires under the Inquiries Act 2005

But why are public inquiries now so commonly created and what does this say about the changing nature of British politics? And how might a ‘new’ politics of public inquiries be emerging? This article uses the recent report by the Statutory Inquiries Committee (SIC) of the House of Lords as a starting point on this ‘inquiry on inquiries’.

The old politics of public inquiries

Public inquiries have generally been used to investigate matters of serious public concern since two scandals in 1913 and 1921. Ministers decide whether an inquiry should happen, define its terms of reference, dictate its resources, appoint the chair, receive the final report and ultimately decide whether to accept or reject its recommendations.

The traditional focus has generally been on the degree to which they are truly independent or whether they are used by governments to kick tricky topics into the long grass.

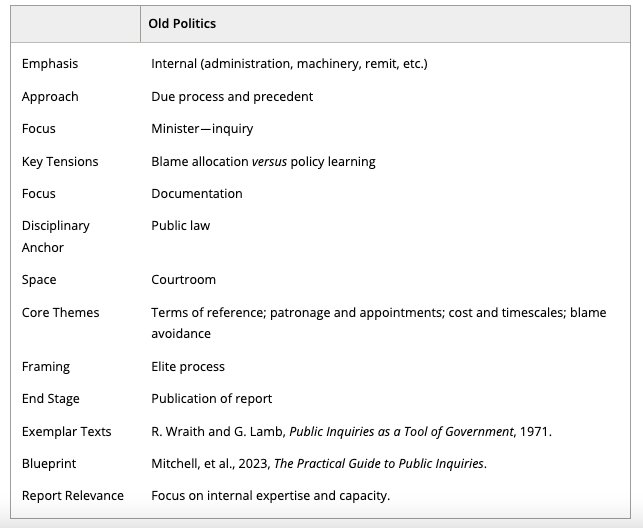

Table 2 attempts to chart the broader parameters of how public inquiries have traditionally been discussed in public, debated in Parliament and studied in academia. Public inquiries remained elite processes, with little emphasis on public engagement.

Table 2. The old politics of public inquiries

The study of inquiries was until the twenty-first century generally a matter for public law scholars rather than political scientists. They were generally viewed as having two largely incompatible roles: blame allocation for what went wrong and policy learning to prevent things going wrong in the future. This explains why a common criticism was that many inquiry reports tended to be ‘left on the shelf’.

A boundary-spanning inquiry

The SIC's 2024 report should be seen as highly significant because it points to the emergence of a ‘new’ politics of public inquiries, and straddles both the old and the new politics of public inquiries. The skill of the report is that it manages to operate within the Westminster tradition of ‘continuity and change’.

The first focus of the report is within the old politics. ‘Inquiries make too many avoidable mistakes and fail to learn from the experience of earlier inquiries.’ The 2014 report on the Inquiries Act 2005 had come to the same conclusion and had recommended the establishment of a central inquiries unit based within the Cabinet Office. Four years later, an inquiries unit was established in the Cabinet Office, but its size, scope and impact were found to be deficient ten years hence.

The SIC's second main recommendation attempts to shift the balance of power between the executive and legislature. It concluded that insufficient implementation monitoring has damaged the reputation of public inquiries and made them less effective.

This conclusion led the committee to recommend the establishment of a joint select committee of Parliament—a public inquiries committee—which would, inter alia, monitor the implementation of accepted recommendations, maintain an online tracker, make recommendations to the Cabinet Office's inquiries unit and scrutinise the government's sponsorship of and formal response to individual inquiries. It is this highly strategic and politically delicate recommendation which points to the emergence of a new politics of public inquiries.

However, there are few incentives for a government to make its business of governing more difficult by creating or strengthening forms of parliamentary scrutiny; see Tony Wright’s ‘cracks and wedges’ theory of parliamentary reform whereby initial concessions quickly become the focus of expansionary pressures. Yet if public inquiries are established, but their recommendations are not implemented, levels of public trust are likely to decline further still.

The new politics of public inquiries

Function

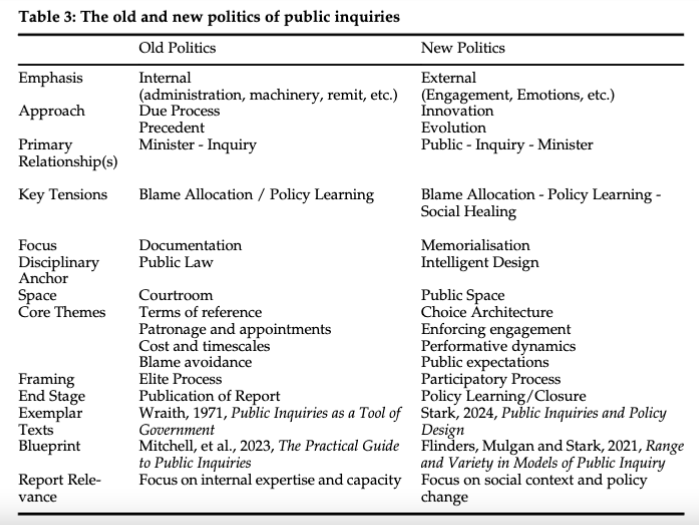

As Table 3 illustrates, whereas the old politics focussed on internal issues relating to process and precedent, the hallmark of the new politics is an emphasis on external engagement. In recent years, inquiry processes have provided an arena for social healing and emotional expression.

Table 3. The old and new politics of public inquiries

The Scottish Covid Inquiry, for example, held a major public consultation around the initial terms of reference. This revealed a strong public appetite for a ‘person-centred’ inquiry. The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse was pioneering in bringing ‘experts by lived experience’.

Coping with complexity is therefore a key element of the new politics of public inquiries which links back to the SIC's call for a bolstering of capacity and expertise at the centre of government—not least as inquiries are generally staffed by civil servants on secondment, thus being at odds with flatter, less rigid and more inclusive ways of working.

Form

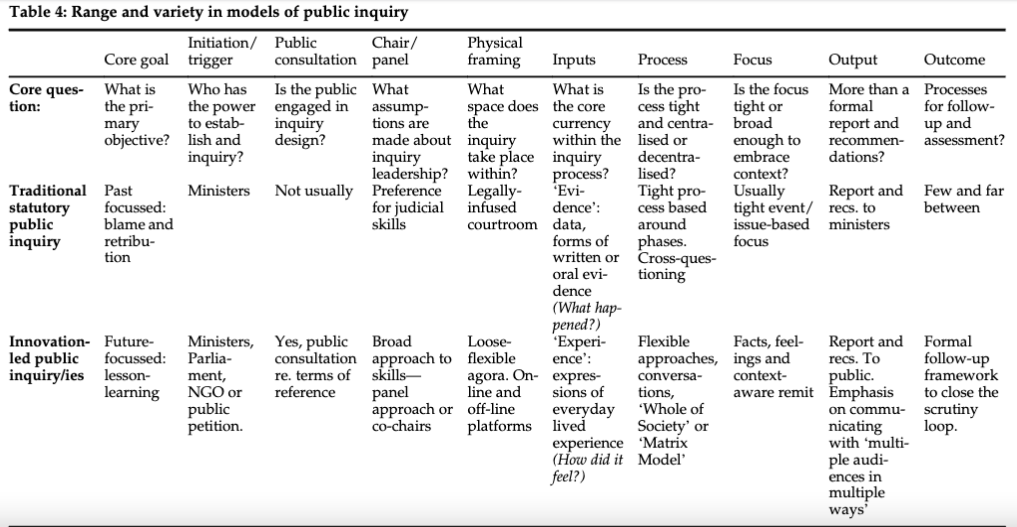

But the design debate is far more advanced than the SIC seems to have recognised, with increasing doubts raised about whether traditional inquiry models are able to cope with complexity. The International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO), for example, took a design-orientated approach that fit form to function in arguing back in 2021 that the Covid-19 pandemic was a uniquely wide-ranging and systemic challenge which could only be fully explored through a non-traditional ‘whole of society’ approach.

Table 4. Range and variety in models of public inquiry

This focus on form can also be linked to rising levels of anti-political sentiment and to the fact that formal public inquiries are increasingly launched not by governments, but by aggrieved citizens or networks of experts. The UK People's Covid Inquiry, for example, was established in February 2021 at a time when the prime minister, Boris Johnson, was procrastinating.

Pathologies, pitfalls and problems

Two-thirds of the public now expect public inquiries to play a role in terms of cathartic healing and memorialising. Returning to Table 3, internal issues concerning due process and independence are now overlayed with a new emphasis on public engagement. Inquiry chairs or panels must also dedicating equal attention to affected communities. Blame allocation and policy learning continues to matter, but now as a tripartite task that includes social healing; documentation has now been joined by memorialisation. The old politics exists within the new.

A greater emphasis on public engagement and social healing, for example, creates new questions about how inquiry processes retain their independence from affected communitiess. Longstanding concerns regarding the costs and length of inquiries are only likely to be exacerbated by participatory processes. Without careful management, they may risk further undermining public confidence in British politics rather than rebuilding it.