| 8 mins read

SUMMARY

- Britain’s political finance regime is dangerous and risky.

- The Political Parties, Elections, and Referendums Act (2000) allows donations of unlimited size, which risks inflating the cost of politics, distorting political competition, and corrupting governance.

- Overall, the threats of inflation, distorted political competition, and corruption do not appear to have been realised yet, but evidence suggests they could happen.

- Reforming the system would be in the interest of the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats.

Justin Fisher has recently argued that Britain’s political finance regime is unbroken. We agree, but we think it is a dangerous system riding its luck. Fisher rightly points to the success of the Political Parties, Elections, and Referendums Act (2000) in delivering transparency, limiting who can donate, overseeing party election spending limits, and establishing a respected regulator. Nevertheless, the system allows donations of unlimited size, including from legal individuals. This creates a risk of a risk of political finance inflation, distorted political competition, and corruption, each of which threaten British democracy. Elon Musk’s musings about donating as much as $100 million to the Reform party make the threat even greater. We argue that the gross disproportionality of the last election and the ongoing volatility in voter preferences means that the rationale for fundamental reform from the point of view of the narrow interests of the three traditional big parties – the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats – is stronger than many realise. First, however, we take a look at almost a quarter of a century of UK political finance data.

Do political donations lead to corruption and other problems?

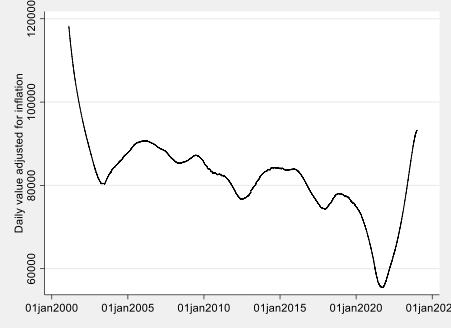

Figure 1: The value of reported donations over £7500. Note: Excludes public funding; Lowess smoothed, bandwidth 0.2. The value of donations is adjusted for changes in the Retail Price Index (Williamson 2024).

Figure 1 shows that donations have not been increasing in value, save a recent spike in the run-up to the 2024 general election. If there has been any trend, it has been downwards. Britain’s system of unlimited donations does not appear to have made politics more expensive. We now move on the trickier question of political competition.

We compared the inflation-adjusted value of donations to monthly intention-to-vote polls across the whole period. By this measure, the Conservatives and Labour received very similar amounts of donations. By contrast, the value of donations to the Liberal Democrats is disproportionate to their popularity. They received an average of 2.5 times as much in donations per intending voter as did the two big parties.

Even if the donations received by the larger parties have on aggregate been proportionate to their intended vote shares, the popularity of the parties may have been distorted by the value of donations. Our analysis shows that the Conservatives were the only party for which poll scores and the value of donations were correlated. This means that the Conservatives may have been able to buy popularity, which would be very concerning. It could also mean the opposite: that donors only gave to the Conservatives when it was more popular. We can also see that the Conservatives were the only party to take in more money when in government. This may fit a story of fair-weather Tory donors, or influence-seeking Tory donors. Overall, there is some evidence that donations distort political competition. However, it is inconclusive and confusing.

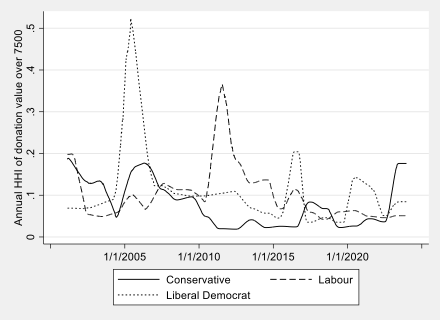

Figure 2: The Concentration of Donations

The greater the parties’ dependence on particular donors, the greater the potential for corruption. The Hirschmann-Herfindahl Index (HHI) is a standard index of concentration. Figure 2 shows that the Conservatives had the lowest and most stable concentration of donations over the period. Having lots of large donors makes it easier to say ‘no’ to any single donor. By contrast, there are spikes in the level of concentration of Labour and Liberal Democrat donors, which reflects the impact of large donations to parties that do not receive as many large donations. However, the type of donor matters. Obviously, trade unions are less of a corruption risk than individual donors, who are, in turn, less of a risk than companies. Corporate donations are much more likely to be self-interested, while donations from individuals tend to reflect the ideology of the donor. The Conservatives, of course, have been the most dependent on company donations. Donations by British companies are vanishingly rare at the scale of the economy: we calculate that the average rate over our period was less than one per cent (0.72). If donations could reliably buy influence, there would be more of them.

Overall, the threats of inflation, distorted political competition, and corruption do not appear to have been realised.

Why we need political finance reform

We contend that the rationale for reform, in the narrow self-interest of Britain’s political parties, is stronger than commonly believed. The British political system is currently highly volatile, since the fragmentation and fluidity of voter preferences are magnified greatly by first-past-the-post in the UK. In this context, public funding can offer insurance against electoral disaster. The recent local elections will have reminded Labour that their current majority is an artifact of the most disproportional election in British history and they could be the victims of disproportionality in the future.

Given the situation of the three parties, if political finance becomes a problem for Labour, it may see the rationale for reform. Sir Keir Starmer has already endured a personal political finance scandal of sorts by accepting gifts, including Arsenal tickets, from prominent Labour backers. Should another one arise, long-term thinkers in the Labour party may see an opportunity for a deal: restrictions on business and union donations, together with public funding of the day-to-day running of political parties.

Our political finance system is risky

Our new data bolster Fisher’s positive assessment of the last twenty-five years of British political finance. The problem with the UK’s political finance system is not so much how it operates, but what could too easily happen. Allowing donations of any size risks inflating the cost of politics, distorting political competition, and corrupting governance. Denying parties meaningful public funding increases that risk yet further. Donations have not made British politics more expensive. There is a risk that they have distorted the political system. It is hard to disentangle whether donations have followed or boosted Conservative popularity. These calculations matter most if donors are influence-seeking and it seems that most big donors have been ideological supporters of parties rather than pragmatic actors. However, this has been a matter of trusting to the ‘good-chaps’ theory of government, which is not too far from hoping for continued good luck.

Electoral volatility is on everybody’s minds and political finance reform is a way to partially insulate political parties against electoral volatility, as well as reducing the risks of inflation, distortion, and corruption. Maybe Britain needs a medium-sized political finance scandal that puts reform on the agenda of the Labour government.

Digested read created by the authors with editorial support from Anya Pearson.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley