| 6 mins read

Salvador Macip has written an accessible survey of pandemics during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, charting warnings and lessons for future pandemics and the survival of the human species.

A new super virus?

Several themes run through the book. First, more deadly and transmissible pandemics than our present Covid-19 are inevitable, and Macip predicts they will most likely arise from a virus that has accompanied human civilization since at least the sixteenth century – influenza.

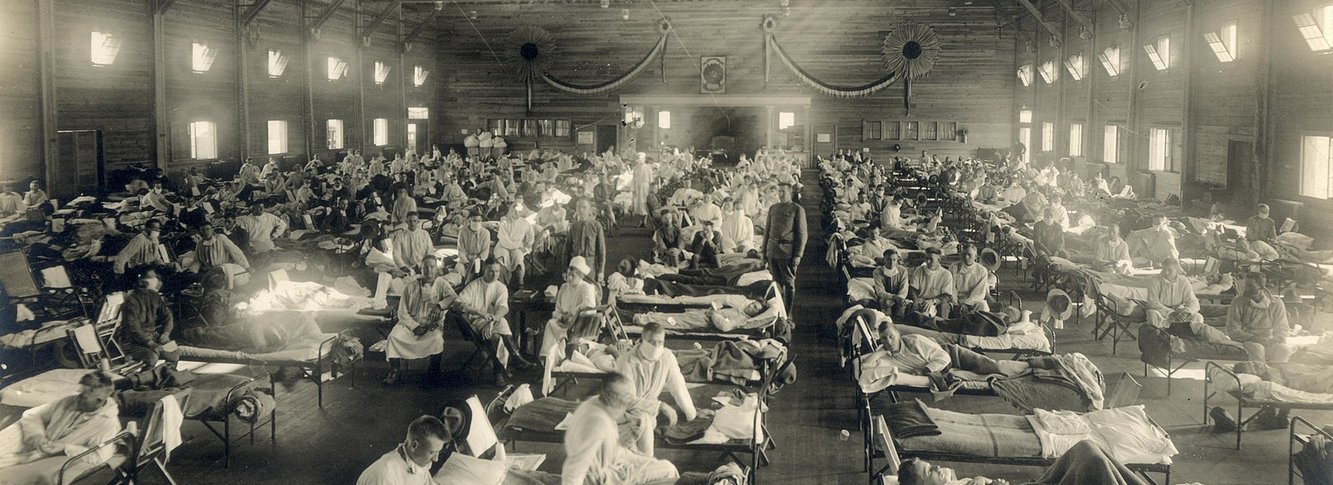

From 1920 to the present, humans have been lucky: variations in influenza threats have either been more transmissible than the usual flu, as with the swine flu (H1N1) in 2009, or more lethal as with bouts of bird flu (H5N1), when as many as 50 per cent of those infected have died. These two characteristics, however, have not come together since 1918 in an influenza pandemic estimated to have decimated between 50 and 100 million people.

For outbreaks of bird flu, the number of cases infecting humans has remained miniscule. As for the swine flu of 2009, its extraordinary transmission was mostly limited to Mexico and to its initial stages. The flu did not exceed the usual range of annual influenza mortalities.

However, according to Macip, the probabilities are high of an influenza strain of high transmissibility and another of high lethality attacking a pig or human at the same time, thereby exchanging genetic information and creating a new super virus.

The re-emergence of old diseases

Second, Maclip focusses not only on new viruses, but also on old diseases, such as cholera, which have re-emerged in crisis-stricken places such as Haiti, Zaire, and Yemen, as well as tuberculosis and malaria that continue to spark high mortalities because of new levels of bacterial aggressiveness or, in the case of tuberculosis, from antibiotic resistance.

These old companions have become significant demographic threats even in places such as New York City, more so than most new epidemics.

Rays of optimism

Nevertheless, optimistic rays shine through this book, especially when considering scientific breakthroughs since the late 1960s. Research has revolutionised developments in new antiretroviral therapies and vaccines. For starters, no longer do vaccines need to rely on the production of billions of hens’ eggs, often with little warning.

Moreover, success in controlling big killers, such as malaria, can rely on the distribution and management of old technologies such as insecticides, mosquito nets and preventive treatments. In In Gambia, cases have shrunk by 90 per cent since 2003.

Listening to the wrong people

This leads to another theme: ‘Science alone isn’t enough to defeat infectious disease’. Here, Macip emphasises communication, trust, effective management and adequate investment in new research.

Remember the effective and long-lasting anti-vaccination campaign triggered by Dr Andrew Wakefield in 1998? His fallacious research published in The Lancet accused the triple viral vaccine against mumps, measles, and rubella of causing autism. As a consequence, cases of mumps alone soared by almost 300 times during the following decade.

Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics during the past thirty years has stimulated the resistance of pathogens. Profit motives in the drug industry run counter to careful and restricted use of antibiotics. As a result, capitalist incentives fail to support needed research for new antibiotics.

Even worse in costs to human lives have been government leaders’ denials of new diseases, conspiracy theories and widespread misinformation. South Africa's ex-president, Thabo Mbeki, may win the prize for his denial that HIV did not cause AIDS, his quack remedies and his blockage of new antiretroviral drugs in 2002–3 that cost the lives of at least 330,000 in South Africa.

Macip recommends not ‘listening to the wrong people’, but he doesn’t explain how such advice would be implemented. This is particularly apposite in our current pandemic, when heads of states have as in Tanzania, Brazil, and the US relentlessly peddled false information concerning Covid-19.

Macip's work contains various historical inaccuracies, however. For instance, he claims that the plague of Athens (430 BCE) is ‘the oldest epidemic on record’; but five pages later mentions the plague that afflicted the Philistines.

Furthermore, he claims that medicine in the USA during the influenza pandemic of 1918 supposedly relied on blood-letting and Aristotelian theories of the humours, and that government policies and advice in the US were steeped in claims that this pandemic was no worse than the usual seasonal flu. Contemporary newspapers and other documents tell another story. Municipal and county decrees closed many public venues and recommended or made masks mandatory. Moreover, the Surgeon General's detailed advice was published daily in hundreds of newspapers across the country in October and November 1918, concentrating on measures for social distancing, avoiding crowds, and personal hygiene that have now become familiar with us.

However, to end on a positive note, while this work may not introduce novel proposals on medical management to contain our present pandemic or ones in the future, it presents a readable and well-balanced survey of the threats we face – not only with coronaviruses, but across a broad range of pathogens, and suggests pathways for future coexistence with our microscopic neighbours.

Modern Epidemics from the Spanish Flu to Covid-19, by Salvador Macip, translated by Julie Wark, is published by Polity Press. 288 pp. £14.99.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley