| 9 mins read

The 2024 British general election was a classic valence election, with voters seemingly casting their ballot based on the record of the incumbent, rather than owing to great enthusiasm for any of the alternatives. Despite the massive swing against the Conservatives, the structural cleavages that underpin the electoral geography of Britain only shifted slightly largely consistent with the geography of the 2019 ‘realignment’.

More widely, the election took place in the context of a mood of deep public distrust in politics and a high level of fatalism. In April 2024, 82 per cent of people agreed with the suggestion that government tends to offer ‘empty gestures’ instead of tackling important problems.

Several features of the political context contributed significantly to patterns of voting. First, the splintering of support on the Leave side had devastating consequences for the Conservative party, as well as being a significant part of wider electoral fragmentation.

Second, there was the declining partisan loyalties of voters and increased electoral volatility, reflected in the lowest combined share of the national vote for the Conservatives and Labour—57.4 per cent—since 1918. More and more voters were willing to look beyond the main two parties. Interestingly, this did not lead to significant volatility in electoral geography as the effect was at most a slight atrophying of certain long-term trends at the aggregate level.

Third, the election was characterised by a patchwork of electoral competition across Britain. The unpopular SNP was the incumbent in Scotland, and the scandal-ridden Labour was the incumbent in Wales. Reform UK also presented a challenge to the Conservatives and to Labour, especially in former industrial towns. Meanwhile, the Greens posed a threat to Labour in more cosmopolitan urban areas such as Bristol.

The changing electoral geography of England and Wales

Drawing on harmonised demographic and electoral data over the period between 1979 and 2019, this article extends the analysis of Furlong and Jennings to the 2024 general election.

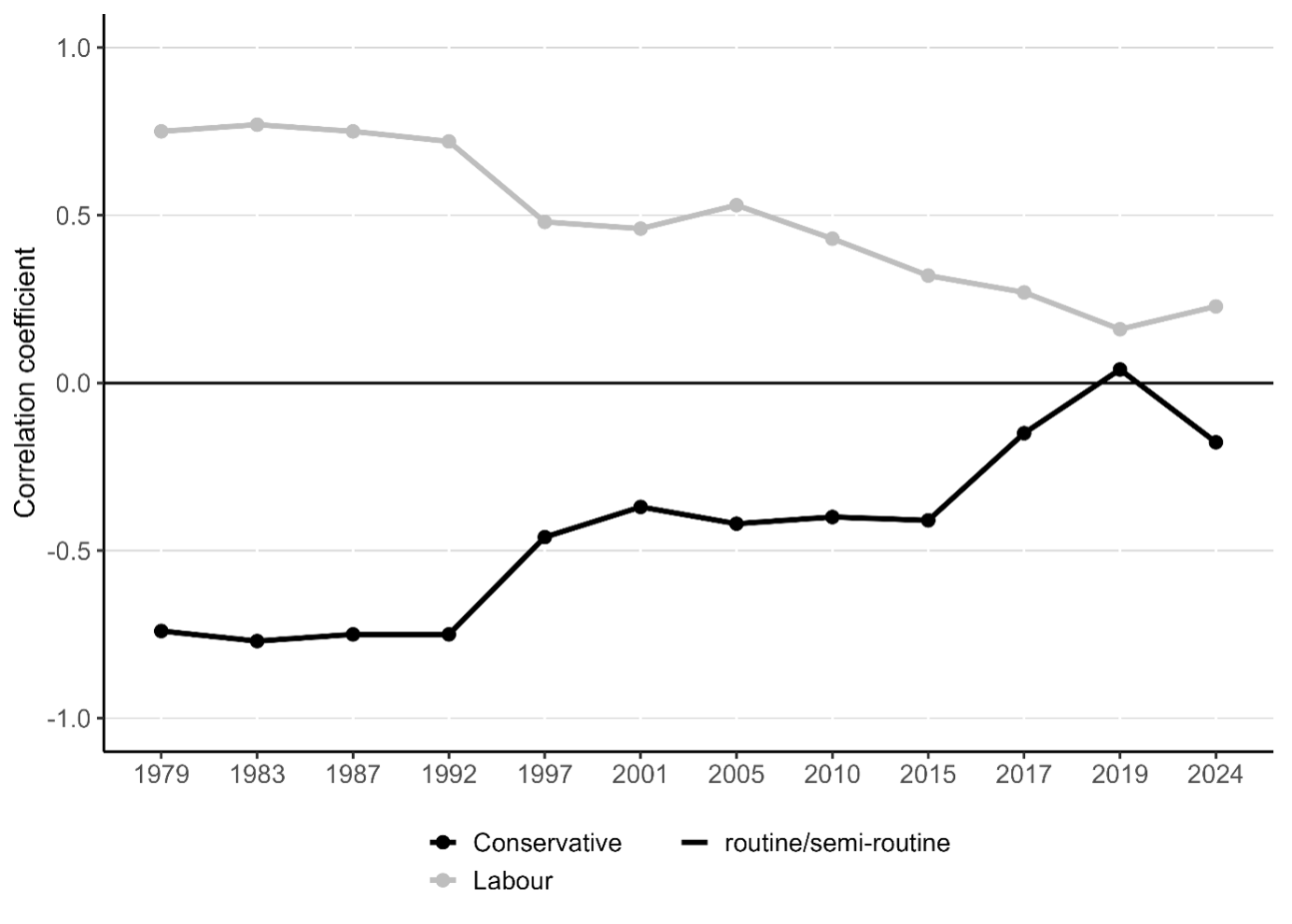

Beginning with social class, there has been a long-term decline in the strength of the positive correlation between the proportion of people in working class jobs (routine and semi-routine occupations) and Labour's vote share, as shown in Figure 1.

Since 2015, the Conservatives had seen an increase in the correlation coefficient to the point that it was marginally positive in 2019. Nevertheless, the long-term picture remains one of dealignment—rather than realignment—of class-based differences in electoral geography: an area being heavily working class is not a strong predictor of the Conservative vote share and nor was it in 2019, contrary to what a great deal of commentary would imply.

Figure 1: Correlation between working class occupations and party vote share, 1979–2024

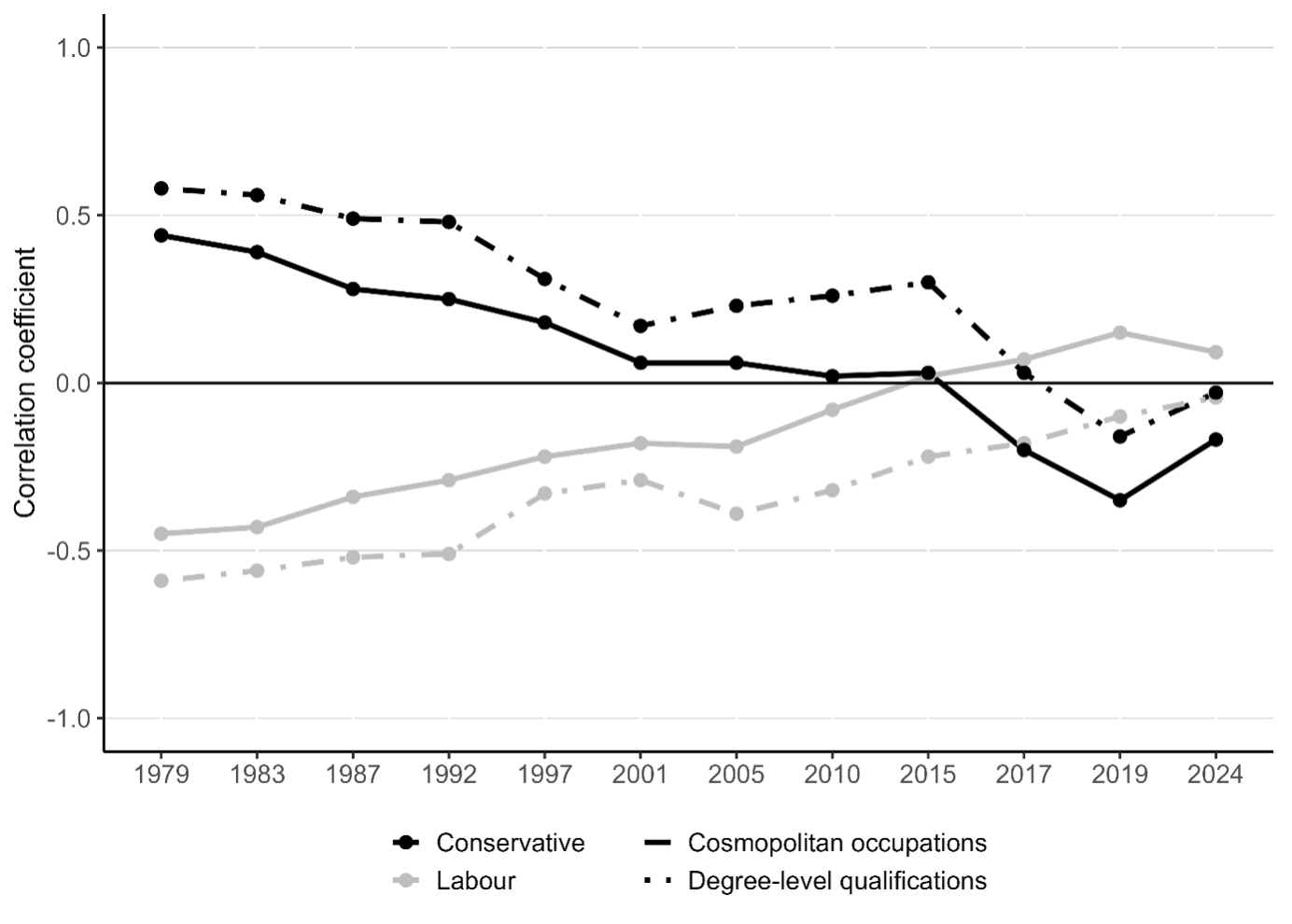

The reverse of this trend is observed for the relationship between education and the Labour and Conservative vote shares, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Correlation between degree-level qualifications and party vote share, 1979–2024

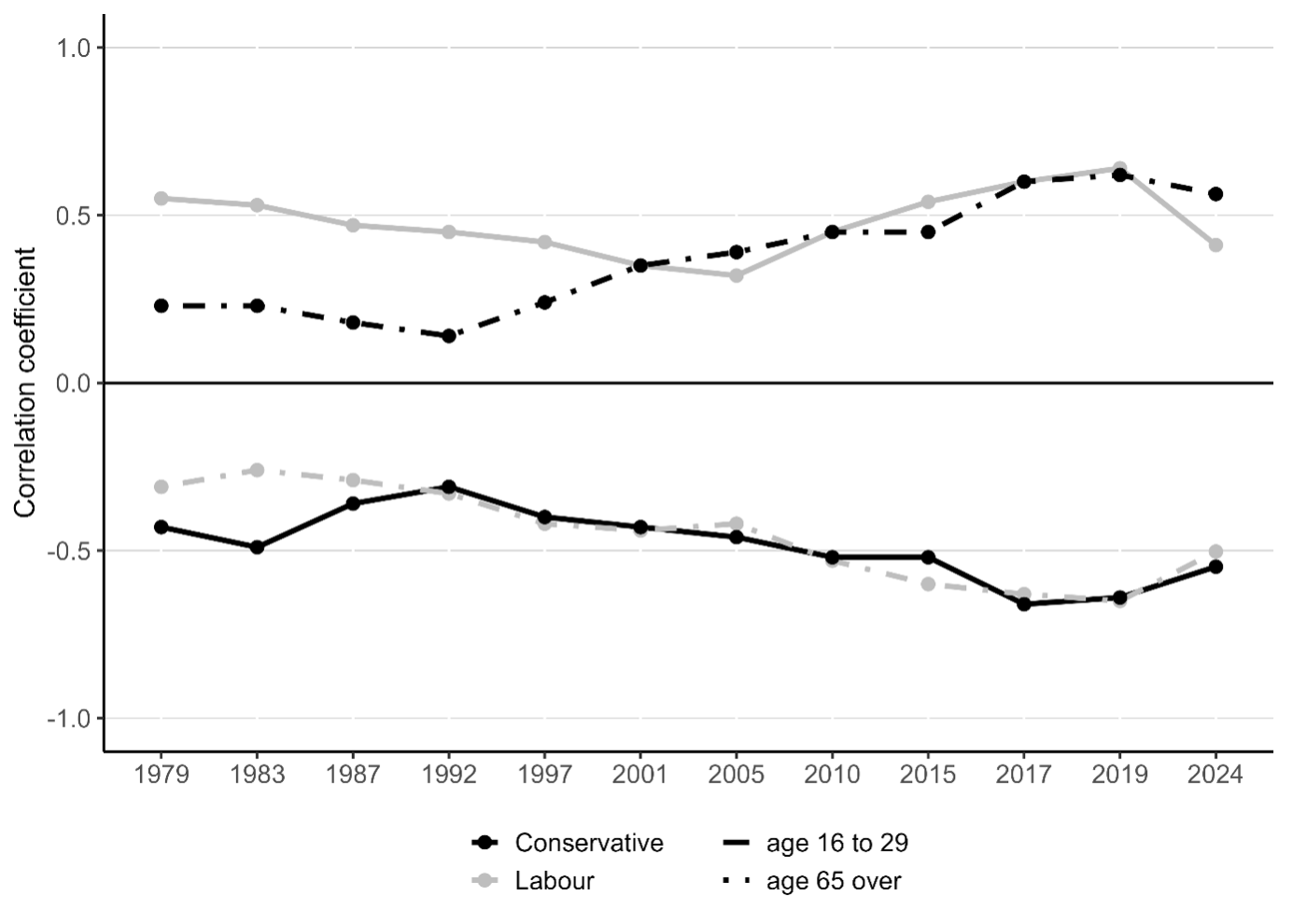

There is evidence of a growing age cleavage at the constituency level. This is demonstrated in Figure 3. Labour's support has decreased in areas with higher proportions of over-65s and increased in those areas with higher proportions of the under-30s since 2010. The vote in 2024 saw a slight reversal of this long-term trend. Indeed, the correlation between the proportion of under-30s and Labour's vote fell back to the level observed

Figure 3: Correlation between age and party vote share, 1979–2024

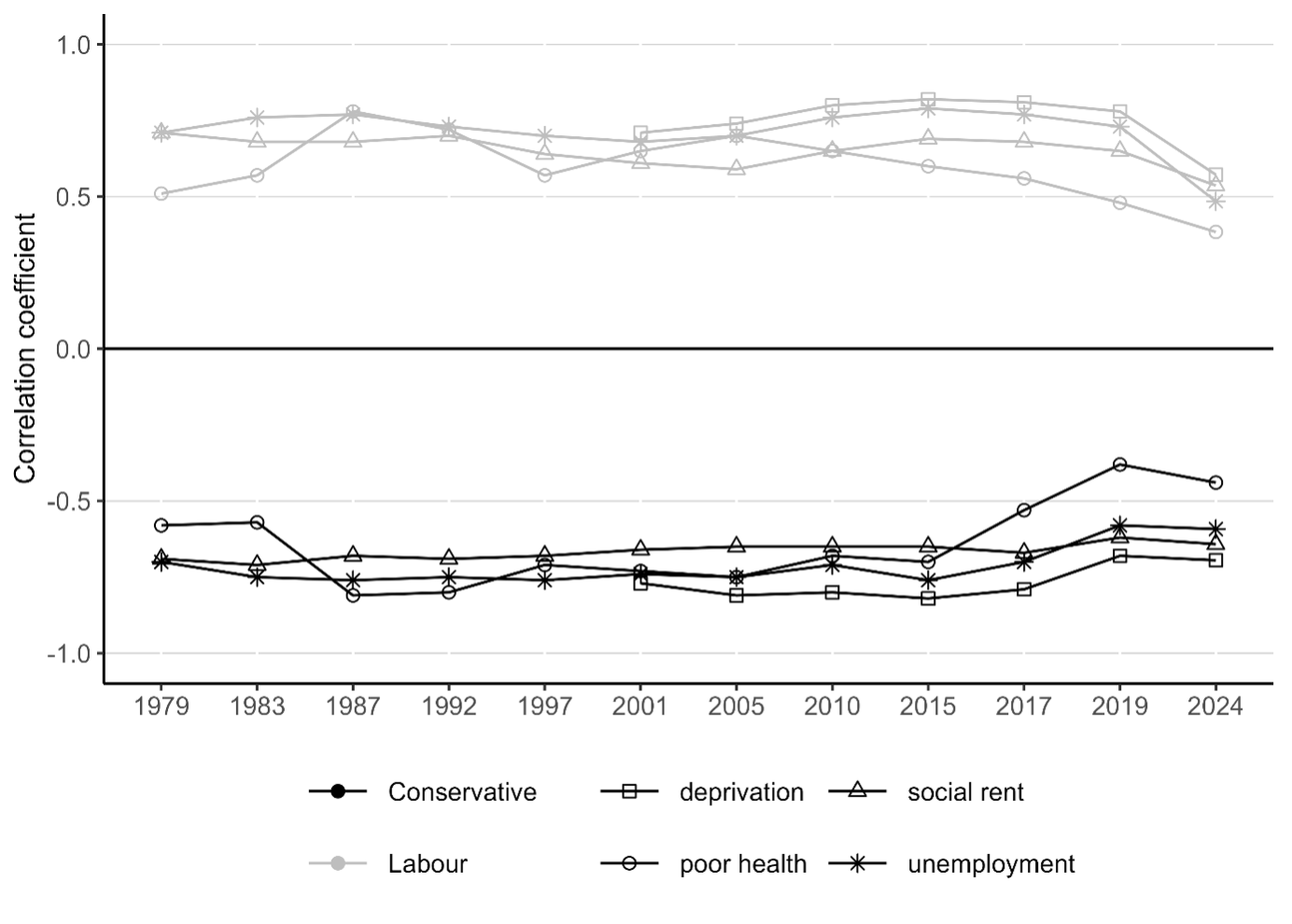

In contrast to the trends described for social class, education and age, Furlong finds that such socioeconomic ‘left-behindedness’ has been a much more consistent predictor of the geography of Labour's vote. Poor health declined slightly as a predictor of Labour's vote share in 2024—as shown in Figure 4 below—while there was a slight decline in the correlations for deprivation, social renting and unemployment.

Figure 4: Correlation between deprivation and party vote share, 1979–2024

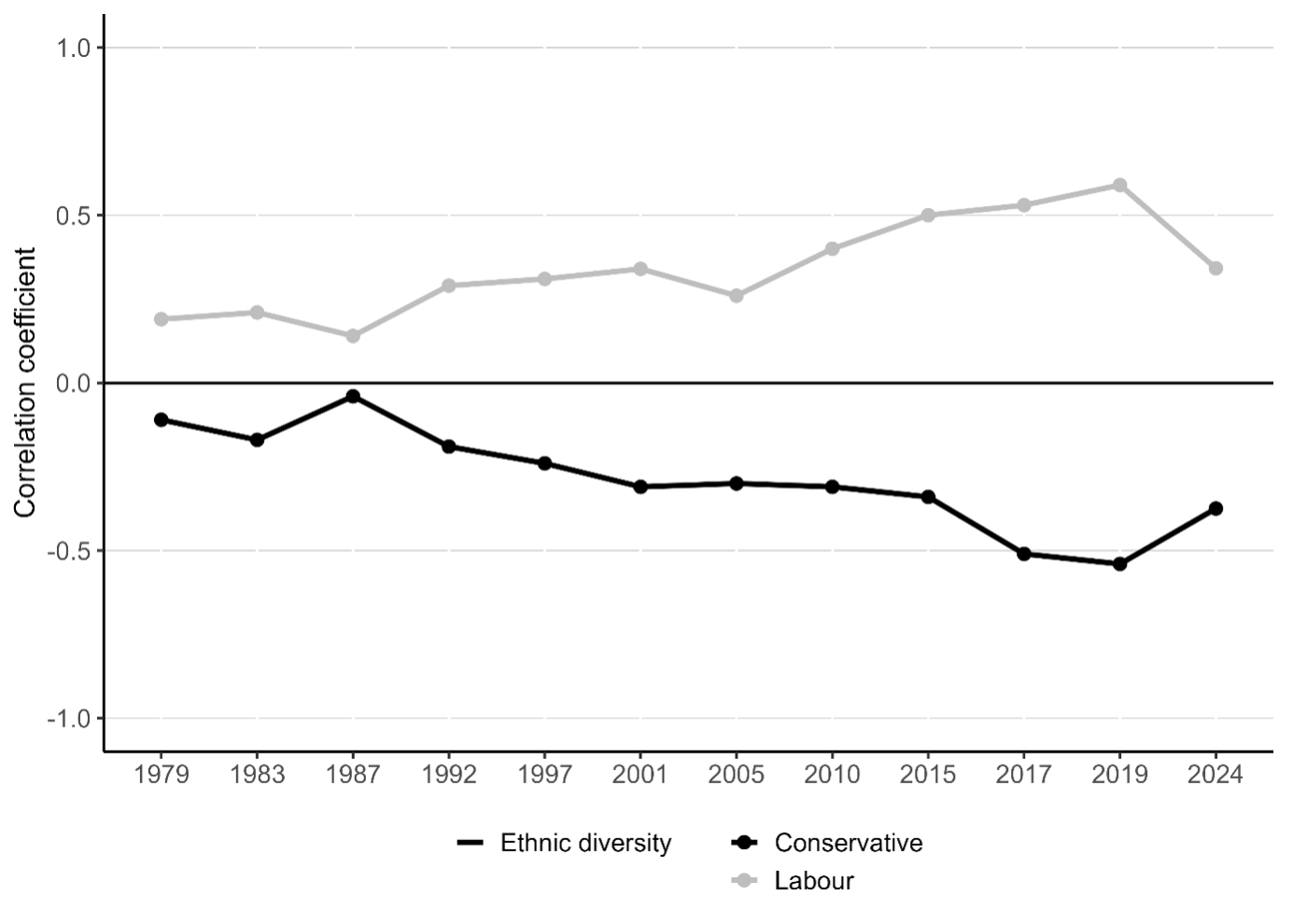

Lastly, since 1979 there has been a growing positive correspondence between ethnic diversity and Labour constituency vote share and an increasingly negative correspondence with the Conservative vote share, as shown in Figure 5. This long-term divergence contracted notably in 2024.

Figure 5: Correlation between ethnic minority and party vote share, 1979–2024

Places where the parties under- or over-perform

One of the puzzles of electoral geography is the places where voters do not follow faithfully the script set by their social and economic profile. There continue to be places in England and Wales that defy predictions based on demographic variables. Using a spatial analytical approach known as ‘local indicators of spatial association’ (LISA), figures 6 and 7 show maps for the 2019 and 2024 general elections to enable comparison.

Figure 6: LISA cluster map showing statistically significant clustering of standardised residuals (under- and over-performance) from the 2019 and 2024 models predicting Labour vote share

Figure 7: LISA cluster map showing statistically significant clustering of standardised residuals (under- and over-performance) from the 2019 and 2024 models predicting Conservative vote share

For Labour, its cluster of over-performance in 2024 overlapped substantially with that observed in 2019, covering substantial areas across northern England, including large parts of Merseyside, Manchester and parts of Yorkshire in and around the Pennines. Notably in 2024, the party's strong electoral showing spread to include rural parts of the far north of England—as far north as Hexham and North Northumberland, seats it won for the first time ever in 2024. New ‘low-low’ clusters appeared in southern England in 2024, reaching from the southwestern edge of London across to Devon. These tended to be in areas where the Liberal Democrats were the main challenger to the Conservatives.

A fragmented electoral map

The underlying geography of Conservative and Labour electoral support appears to have remained largely stable between 2019 and 2024. The most notable shift in electoral geography at the 2024 general election arguably relates to the increased fragmentation of electoral competition.

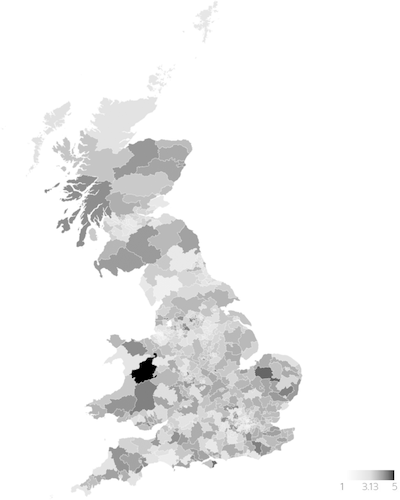

The ‘effective number of electoral parties’ (ENP) is a well-established measure of electoral fragmentation. At the national level (Great Britain), ENP increased by more than one party from 3.1 parties in 2019 to 4.5 in 2024. In some areas, the vote is spread relatively evenly across several parties competing fiercely (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Effective number of parties by parliamentary constituency, Great Britain, 2024

Marginality: the fragility of the electoral future

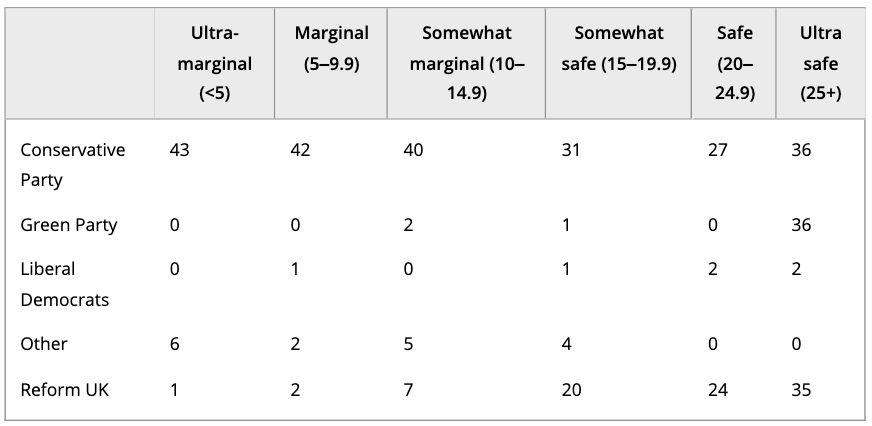

This fragmented electoral map was also reflected in the growth of the number of marginal constituencies. At the 2019 general election, there were 135 constituencies in England, Wales and Scotland with a majority for the winning party of less than 10 per cent, including sixty-three with a majority under 5 per cent. In 2024, this increased to 217 constituencies with a majority of less than 10 per cent, including 112 under 5 per cent.

Table 1: Second-placed party in Labour-held seats by marginality of parliamentary constituency, 2024

An uncertain, unstable future

With the electorate now more volatile, discontented, dealigned and fragmented, what are the prospects for the new Labour government? The prospects for restoring public faith in politics and the capacity of government to deliver look bleak.

Labour's immediate challenge of taming Britain's recurring economic crises will ultimately determine its electoral future. Meanwhile, the Conservatives face a pincer movement from Reform on their right and the Liberal Democrats on their left. It is these forces that are accelerating the dynamics of electoral fragmentation. It remains difficult, however, to make confident predictions about what the electoral geography of England and Wales might look like at the next general election.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley