| 7 mins read

Have you ever felt that you were standing at a critical historical juncture? Many Turks certainly felt that way on the eve of 14 May 2023, the day of the parliamentary elections and the first round of the presidential elections. Many polling companies predicted a close race, yet most argued that the opposition candidate, Kemal Kılıçdaroglu, was likely to win. Social media and opposition rallies were bursting with excited opposition supporters ready to turn the country towards a more democratic, secular, and pluralistic route. Given woeful economic circumstances and a series of incompetencies in public policy, the opposition was hopeful.

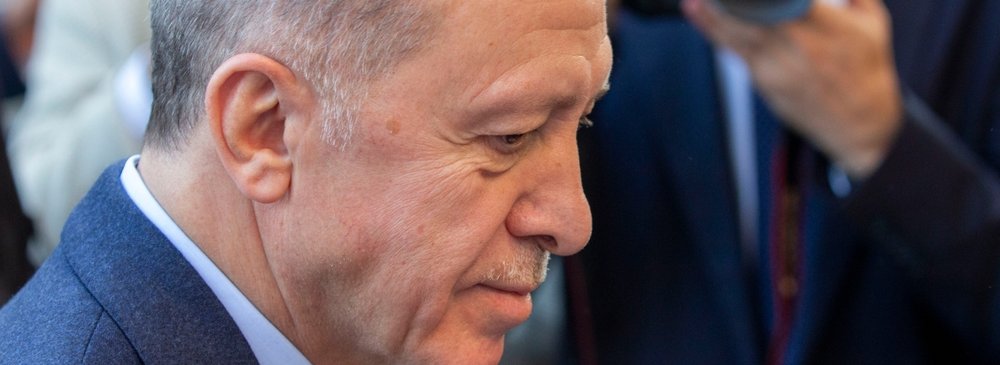

Yet, change did not materialise. The AKP-led alliance managed 49.68% of the votes for the parliament, the AKP’s share being 35.78%. Their alliance gained 323 seats out of 600. Erdoğan received 49.24% in the presidential election’s first round and 52.18% in the second. So, what were the underlying dynamics that sealed the fate of Turkey’s 2023 elections? Upon close inspection, the unprecedented use of the state apparatus in favour of Erdoğan and the AKP, plus the balance of relations between the EU and Turkey resulting from the refugee deal, stand out as the most consequential factors. Could an alternative candidate win? That is a counterfactual that we cannot answer with certainty. What we know, however, is that these issues also constrained alternative candidates.

The State Apparatus and Beyond: Courts, Security forces, and the Media

Under Erdoğan, state bureaucracy is viewed as an extension of rule. The AKP strengthened its grip on the judiciary, starting with the 2010 referendum, which made court packing possible. In an unprecedented court case, opposition politician and Istanbul mayor İmamoğlu was given a prison sentence for calling those who made the re-run decision for the 2019 Istanbul mayoral elections ‘ahmak’ (fools). The original judge, who stated that a prison sentence was not possible because of prior legal precedent, was removed from the case and a pro-AKP judge swiftly appointed. Alongside the judiciary, security forces have been used in the AKP’s electoral campaigning. When İmamoğlu organised a rally in support of Kılıçdaroğlu, security forces stood by as pro-government thugs stoned İmamoğlu and those attending.

Mainstream Turkish media have also been consolidated in the hands of pro-government owners. They have become instruments of pro-government propaganda and have received lucrative deals, including public procurements and advertising, alongside the use of public broadcasting. As of 3 May 2023 (eleven days before election day) Erdoğan had been given 32 hours of coverage on TRT, a main public broadcaster, versus 32 minutes for Kılıçdaroğlu. Meanwhile, a handful of media sources not owned by pro-AKP media bosses faced harsh punishments such as fines and halting of their broadcasting by the media regulator. Erdoğan’s media domination has allowed him to escape accountability by journalists to whom he would have to respond to under a democratic media environment, on issues like his disastrous economic programme, his government’s dealing with the earthquake in February 2023, or his alliance with the fundamentalist political party Huda-Par.

The European Union

If certain authoritarian-leaning regimes do not become fully authoritarian, it is not because their leaders do not want to. Rather, it is because they cannot shake off the competitiveness of their political system. In the Turkish case, proximity to the EU has often been viewed as a positive democratic influence. When the AKP first came to power, it expressed its willingness to cooperate with the EU and, at the time, the main motivations for the party were to signal discontinuity with its political Islamist roots. With its second term, a significant decline in the AKP’s pro-EU attitude became visible. The rise of far-right parties in Europe further convinced many Turks that the EU was never going to welcome Turkey, further reducing the EU’s impact on Turkish politics.

With the war in Syria, a new chapter began. Refugees became a source of rentierism for the AKP thanks to the party’s role in keeping refugees away from EU borders. The 2016 deal, in which Turkey receives €6 billion, stipulates that Turkey increases border security and allows Greece to return ‘all new irregular migrants’ to Turkey. In return for each returned migrant, the EU admits one registered asylum seeker from Turkey. But that is not the only form of rent. Erdoğan also gets a pass for his breaches of democracy. Erdoğan does not, for instance, recognise the European Court of Human Rights decisions to release political opponents. Yet, Erdoğan can get away with it without sanction from the EU because he is able to blackmail them with the refugee issue.

The Era of Democratic Backsliding

One perspective is that Turkey has passed the threshold and has eroded into an electoral autocracy. However, the oscillation of the Turkish case makes this a complicated question. Regimes usually do not lose their competitiveness from explicit changes in election laws. Rather, in the spirit of democratic backsliding, the competitiveness of a political regime is rubbed away by slow and incremental moves, election after election. For example, if certain political candidates, such as İmamoğlu, are seen as a challenge, they become the target of the government-led judiciary. Before we know it, there is the risk that while the opposition and the international arena accept the rules of the game as competitive, the incumbent might have made a win for the opposition almost impossible.

Given all the bullying, lies, and violence the AKP were able to use, and given there was almost no way for the opposition to counteract these attacks, it is debateable whether there exists unsubstantiated optimism for the opposition. They claim that elections can be won against all odds as long as electoral competition exists, meaning that elections are not fixed by the incumbents in advance. This tendency provides an optimism for future elections and creates an illusion of a possibility for change via the electoral process, thereby granting the incumbent further legitimacy.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley