| 8 mins read

It is no secret that local government in England is in a perilous position. The increasing burden of statutory demands, including the spiralling cost of adult social care, has eaten away at budgets drained by austerity and caps on council tax increases. Over half of councils report they have insufficient staff to run all services normally. However, there are two structural issues facing local government related to funding and structure.

Funding

Local authorities cannot go bankrupt in the traditional sense, but when their spending is expected to exceed their income they are required to issue what is known as a section 114 notice.

Since this procedure was introduced in 1988, fourteen councils have issued such notices. Tellingly, ten of these have been since 2020, after a decade or more of austerity that saw local governments’ overall core funding down 9 per cent in real terms, and 18 per cent in real terms per person, by 2024–25 compared to 2010–11. This is coupled with an increased demand for services. The icing on the cake is that councils are unable to increase council tax above certain levels without public approval via a referendum and have no control over the level of business rates.

Whilst the rising cost of social care was cited as a reason for the issuance of section 114 notices in both Croyden and Nottingham, for example, some authorities have issued them for other reasons. Woking Borough Council issued a section 114 notice owing to a budget deficit of £1.2 billion, the result of losses on risky investments made to offset central government funding cuts. Similar things have happened in Thurrock and Slough.

Even for the majority of councils that have not yet issued a section 114 notice the situation is bleak. In February 2024, one in ten senior council figures warned they were likely to declare effective bankruptcy in the next financial year.

The effect of these funding cuts has not been uniform either. Poorer councils which have both a greater need for services and a weaker tax base. Blackpool, the most deprived unitary authority, has a council tax base of £40,890.60, whereas Wokingham, the least deprived local authority, has a council tax base of £76,455.30. Fundamentally, the current system of local government funding is not well designed, it is regressive and it relies on ad hoc government intervention in the form of emergency loans.

Capacity

There are currently sixty-two unitary authorities, with an average population of ~250,000, but their size varies greatly. Research by Andrews, et al. found no evidence for a single optimal size of local government units. There can be, for example, a positive linear relationship, whereby the bigger the local authority the better the outcome, such as on the proportion of household waste recycled; or a negative linear relationship—an example being reviews of child protection cases. Fewer units of local government, does not lead to effective local government across every different competency.

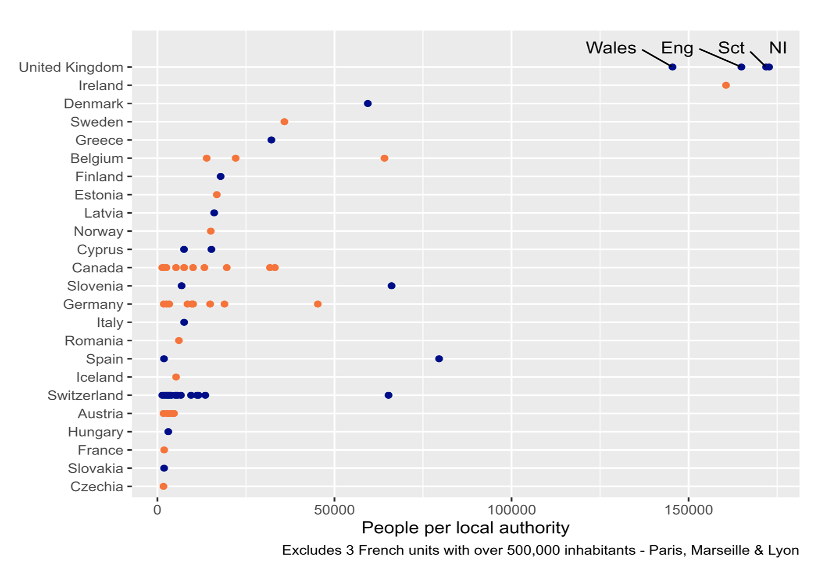

This structural problem with size of local authorities is also underlined by international comparisons, which clearly show just how under-governed the UK is as a country. Figure 1 shows the number of people per unit of local government. In countries where local government is a state-level competency, or with different local government regimes in different parts of the country, state-level averages are presented.

Figure 1: Population per local authority in selected European countries

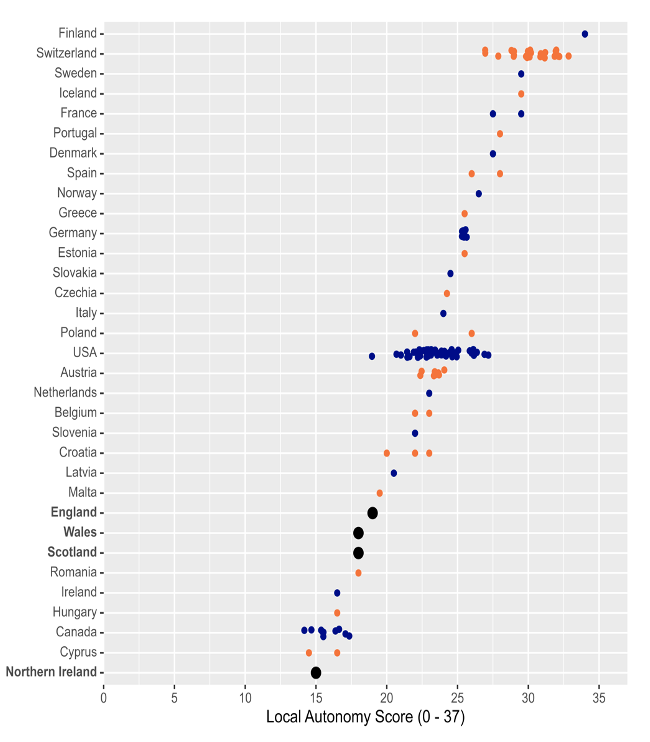

Compared to Czechia, which has an average population per unit of local government of 1,710, the average figure in England is nearly 100 times larger at 165,000. Czechia is on par with Slovakia, Hungary, Austria and even France. As shown in Figure 2, local government in the UK has much less autonomy than local government elsewhere.

Figure 2: Local autonomy scores for selected European and OECD countries.

Taken together, not only is local government ill-suited to deliver the full range of services expected of it, owing to the push towards a one-size-fits-all, bigger-is-better unitary system, but it also lacks the freedom to govern in a way that reflects the needs of their own locales.

One final area of concern around capacity is the fact that so many English local councils are dominated by a single party, which has been associated with poorer performance and more wasteful spending. Councils dominated by single parties could be wasting as much as £2.6bn a year through a lack of scrutiny of their procurement processes and are 50 per cent more at risk of corruption.

Solutions

Local government in England is currently funded by a mix of government grants (22 per cent in 2019), council tax (a property tax levied on residential properties, representing 52 per cent of income) and business rates (a property tax levied on business premises, which makes up roughly 27 per cent of local authority income). However, as argued by Centre for Cities, both council tax and business rates suffer from the same issue in that they are not ‘buoyant’—that is, tax receipts do not increase as economic activity increases. When there are gaps in spending, local authorities make the difference up with grants from central government. This is bad, because it removes an incentive for local authorities to encourage economic growth in their patch.

Instead, local authorities should be funded through a system of taxation that rewards the promotion of economic growth in their area. This could be done through a local income tax or a proportional property tax. Regardless of the method adopted, there will still need to be some element of cash transfer from richer areas to poorer areas.

Structurally, the push for fewer and fewer units of local government must stop and instead a four-tier system should be introduced. Firstly, parish councils—the smallest-sized tier of local council—should continue to cover small areas. Benefits include higher levels of volunteering, charitable activity and satisfaction with social and leisure time.

In addition, all areas should be represented by district and county councils, as was the case between 1973 and 1986, to allow for different competencies to be delivered at the most efficient level, rather than relying on unitary authorities to do everything.

Finally, the ‘upper tier’ of local government should look like something very similar to combined authorities which cover functional economic geographies. All councils should be elected by single transferrable vote to ensure that all councils are always competitive, reflect the views of the local populace and avoid one-party states on the local level.