| 10 mins read

According to the Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s recent statement in the House of Commons, the UK is facing ‘an invasion’. Braverman’s invading army is not made of soldiers but a few thousand ‘illegal immigrants’ who have reached the British shores irregularly, crossing the Channel by small boat.

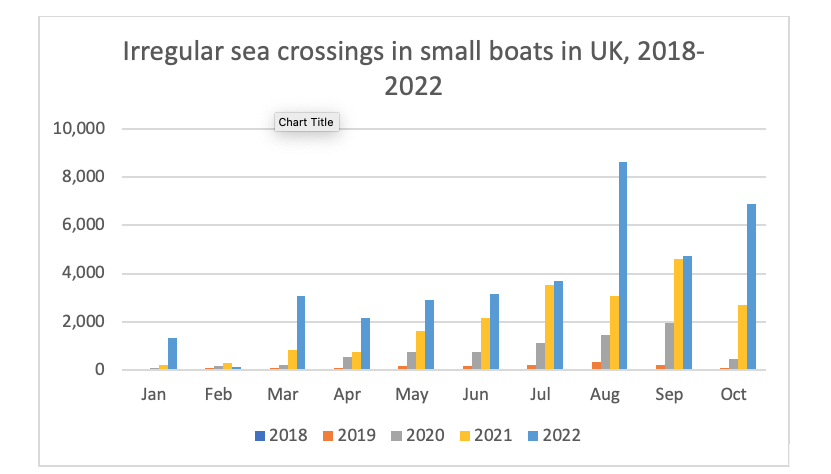

Home Office data show an increase in arrivals since the loosening of travelling restrictions following the pandemic and the end of the Brexit transition period. The scale and magnitude of this so-called ‘invasion’ is one for which, by their admission, the UK government is ill-prepared for, despite the significant human and financial resources thrown at this issue. Beyond the political rhetoric, the scapegoating and displacement of responsibility, there is another story. It’s the story of a self-made policy failure intimately connected to Brexit.

Brexit and the Mediterranean’s ‘refugee crisis’

The images of overcrowded and unseaworthy boats reaching the shores of Lesvos and Lampedusa, migrant dead bodies floating in the sea, and temporary refugee camps appearing in European cities became a familiar presence in British media from the mid-2010s onwards. These images and the threat of a border crisis were a central pillar of campaigns for Britain to the Leave the European Union in the run up to the 2016 Referendum. This included Leave.EU’s infamous ‘breaking point’ billboard featuring a long queue of refugees and migrants and the slogans: ‘the EU has failed us all’ and ‘we must take control of our borders’.

By the time of the Brexit referendum, many public attitude surveys indicated migration as the main concerns for British voters. It didn’t matter that Britain hadn’t experienced a so-called ‘refugee crisis’ first-hand, or that relative to other EU members states the UK only received a very small number of asylum applications. Indeed, it largely seemed to have escaped notice that it was the UK’s membership of the EU and consequent participation in EU-wide migration governance mechanisms that prevented the Mediterranean ‘refugee crisis’ from becoming a British ‘border crisis’. The anti-immigration narratives at the heart of the Leave campaign would continue to drive the political agenda, Brexit narrated and enacted by consecutive Conservative governments as a mandate to take back control of the UK’s borders.

Ending free movement between the UK and EU has been celebrated as a major success by Home Secretary Priti Patel MP, and more recently by PM Rishi Sunak. However, the increase in irregular crossings of the Channel would suggest that things haven’t quite turned out as promised. Further, it is clear that the Government has lost control of the public narrative; a recent Opinium poll revealed 73% of the British public think the UK has not been in control of its borders since Brexit, with 45% thinking that Brexit has made Britain’s ability to manage its borders worse.

An ‘Albanian invasion’

Between January and June 2022, 2165 (17%) out of 12747 of those crossing the Channel in small boats were Albanian nationals. The trend continued over the summer months. According to Clandestine Channel Threat Commander Dan O'Mahoney in his report to the Home Affairs Select Committee, the rise in the numbers can be attributed to the increased activity of Albanian criminal gangs operating in Northern France. In 2021, Albanians only accounted for 3% of small boat arrivals. Other top nationalities were Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian and Eritrean, all nationalities which have a very high chances of being granted asylum by the UK’s Home Office. While small boat crossings and asylum applications are relatively high in the UK at the moment, the UK has received less asylum applications than Germany, France, Spain and Italy this year and when it comes to the number of small boat arrivals, between January and October 2022, Italy has received 83727 people, more than double than the UK.

After twelve years of a Conservative-led Government in the UK, this framing of forced displacement as illegal immigration by those at the helm of the Home Office has become commonplace. From Theresa May’s flagship policy, the ‘hostile environment’, to Priti Patel’s ‘New Plan for Immigration’, finding means of preventing ‘illegal immigration’ has been a central priority. However, despite the rhetorical similarities, one thing is noticeably different. There were only a handful of small boat arrivals during Theresa May’s tenure as Home Secretary. At the same time, elsewhere in Europe hundreds of thousands of refugees were crossing the Mediterranean in small boats to seek refuge in the EU, the UK receiving relatively few of these.

So what’s changed?

Despite the Government’s protestations to the contrary, this is where Brexit comes into play. Rolling back to the early days of May’s strategy to combat ‘illegal immigration’ demonstrates this. It was organised around two pillars: cooperation with France, a fellow EU member state, through the 2003 Le Touquet Treaty, and participation into EU-wide migration governance mechanism laid out in EU legislation such as the Dublin Regulation.

The cooperation with France took the form of "juxtaposed national control bureaus" in the sea ports of both countries. Each country set up immigration control points at the borders of the other, for example the French checkpoint in Dover and the British checkpoint in Calais. The treaty effectively moved the UK border into French territory, contributing to the creation of shanty-camp settlements such as the "Jungle" camp in Calais areas. Other bilateral accords followed in 2009, 2010, 2014, 2018 that laid out that Britain would finance and control security of the border checkpoint sites in France, this includes the so-called ‘Great Wall of Calais’, a 4m high wall running for 1km along both sides of the main road to Calais port. In exchange, it would be up to France to stop migrants trying to enter Britain illegally.

The Dublin Regulation legislates that responsibility for asylum applications remains with the country of first entry in the EU. By design, the treaty was built to favour the interests of northern EU member states in a context where the countries hosting the southern and eastern borders (territorial and maritime) of the EU were more likely to face inflows of asylum seekers and where the tightening up of visa rules and increased use of remote and externalised border controls have made access to safer air routes for asylum seekers from war zones almost impossible.

The UK exit from the EU and, in particular, the decision to pursue what has been labelled a ‘hard Brexit’ strategy, has had an impact on both pillars of UK strategy to combat ‘illegal immigration’. While the Le Touquet treaty is still in force the breaking up in trust between the UK and France – for example Liz Truss’ response to ‘Macron, friend or foe?’ question – has certainly had an impact on the willingness of French authorities to cooperate. Brexit and the repeal of EU legislation has meant that the UK is no longer tied to the Dublin Regulation and other EU-wide immigration control mechanisms.

Anything but Brexit

Brexit means that the UK’s external border has been renationalised bringing with it new governance implications. It is ironic that this process makes irregular immigration to the UK more appealing as it has become more difficult to return people to their country of first entry (in the EU) due to the limited number of return agreements in place with countries of origin and transit.

But this is not the predominant political narrative presented to explain the rise in those crossing the Channel in small boats, or indeed, any other government claimed ‘migrant crisis’. Displacing responsibility for rising numbers onto other nation-states and criminal gangs, scapegoating those seeking to come to the UK via these routes, the narrative is framed around anything but Brexit. The current tensions with Albania regarding the repatriation of Albanian nationals crossing the English Channel irregularly are a case in point. ‘Taking back control’ turned out to have consequences that Brexiteers like Suella Braverman had failed to anticipate, and for which they do not want to accept responsibility.