| 7 mins read

Under the banner of Reform UK, Nigel Farage's rebranded outfit secured more than 4 million votes in the 2024 UK election —14.3 per cent of the total votes cast—winning five seats in the process and performing better than any challenger party has ever performed

Did Reform depend on the same types of left behind voters who had previously backed UKIP? Do the results of the 2024 election suggest a hardening of the social divides that underpinned the rise of UKIP? Or has Britain's Eurosceptic and anti-immigration movement broadened its social appeal?

This article draws on a newly created dataset which maps election results from 1997–2019 onto the constituency boundaries which came into force for the 2024 election, supplemented with individual level data from the British Election Study Internet Panel.

The rise of Reform

Reform UK was founded (as the Brexit Party) in early 2019, following intra-party disputes over the future direction of UKIP.

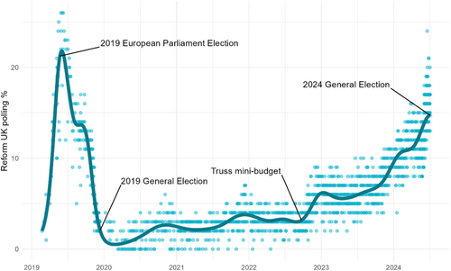

Figure 1. Opinion polling and public support for Reform, 2019–2024. Source: Mark Pack. The solid line shows the estimated smoothed mean, with the 2019 and 2024 general elections weighted to ensure the polling estimates pass through the known results.

The party officially became ‘Reform UK’ in early 2021. After languishing during Boris Johnson's tenure as prime minister, its support began to increase amid the renewed salience of immigration.

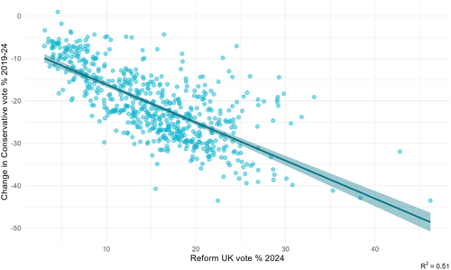

According to the British Election Study Internet Panel, nearly 80 per cent of people who voted for Reform in 2024 had voted for the Conservatives in 2019. Losing so many votes to Reform was catastrophic for the Conservatives whose vote share declined most strongly in places where Reform performed best– see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Swing against the Conservatives and Reform vote, 2024

Who votes for Reform?

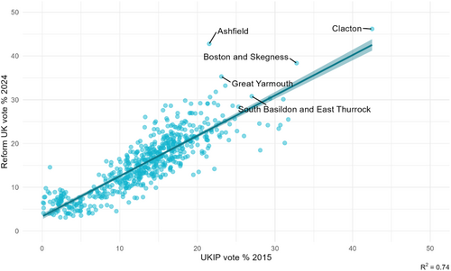

One of the striking features of the Reform vote in 2024 is its similarity to UKIP's vote at the 2015 election, as figure 3 shows.

Figure 3: UKIP vote share 2015 vs Reform vote share 2024

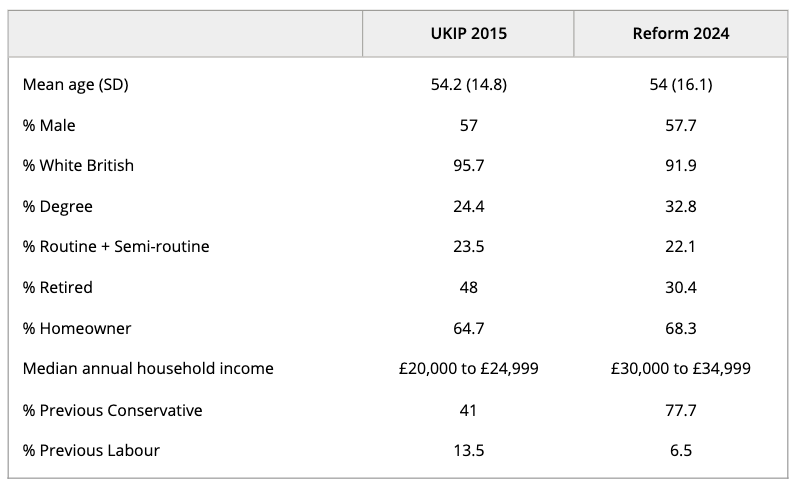

Supporters of UKIP in 2015 and supporters of Reform in 2024 were also very similar, as shown in Table 1 below. However, Reform voters were slightly less white (though they are still overwhelmingly white), more educated, slightly more likely to own their own home and had slightly higher incomes. The most important differences are Reform voters are far more likely to have previously voted Conservative.

Table 1: Social profile of UKIP 2015 and Reform 2024 voters

While the majority of Reform voters did not vote for UKIP in 2015—37 per cent had done so, but slightly more (41.5 per cent) had voted Conservative.

An expanding base: where has Reform gained votes?

In a number of places such as Amber Valley, Rhondda and Ogmore, Great Yarmouth, Reform's vote greatly exceeded that of UKIP. The biggest change was in Ashfield, where former Conservative MP Lee Anderson gained 42.8 percent of the vote, up from the 21.4 percent that Simon Ashcroft won for UKIP in 2015 and up on the 39.3 percent of the vote that Lee Anderson won in 2019 as the Conservative candidate. However, in other places, Reform's vote was substantially down, for example in East Thanet.

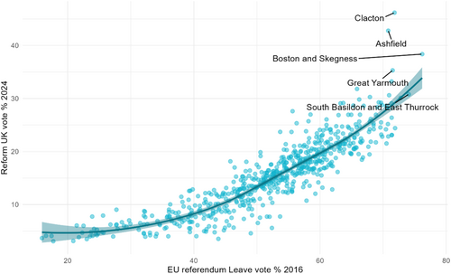

It is perhaps not surprising that there is also a strong relationship between the places that backed Leave in 2016 and the places that supported Reform in 2024 (see Figure 4 ). However, Reform did disproportionately well in the most Leave areas.

Figure 4: Leave vote in 2016 vs Reform 2024

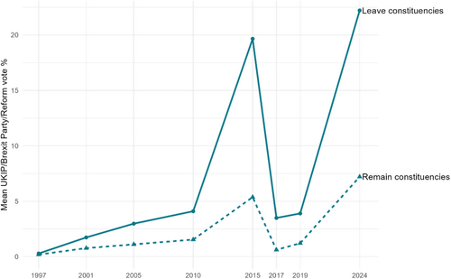

Figure 5 shows how support for Reform and its Eurosceptic predecessor parties have varied over time between those places which were most pro-Remain and those places which were most pro-Leave. Nearly ten years later, Reform's vote share is once again strongest in those places which backed Brexit, overtaking even what UKIP managed previously. Thus, even if the salience of Brexit as an electoral issue has faded, there is little to indicate that the divides that underpinned support for leaving the EU have gone away.

Figure 5: Support for Reform in pro-Brexit and pro-Leave constituencies, 1997–2024

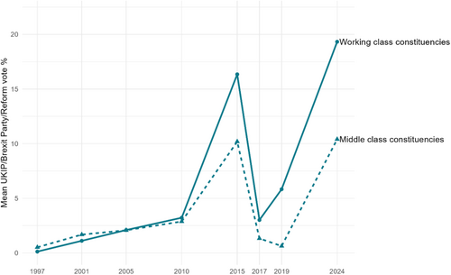

Early work on the rise of UKIP characterised support for the party as a ‘working class phenomenon’ which drew support from disaffected voters who had previously supported Labour. Figure 6 shows that, in the early days of UKIP, there was not much of a class difference between the places where it drew support. However, the gains that UKIP made in 2015 were greater in working class areas than they were in middle class areas.

Post-Brexit, the class gap in support remained and has now become even more pronounced. In working class areas, Reform's vote now exceeds what UKIP ever obtained. Thus, there is some evidence that class divides have become stronger.

Figure 6: Support for Reform in working class and middle class constituencies, 1997–2024

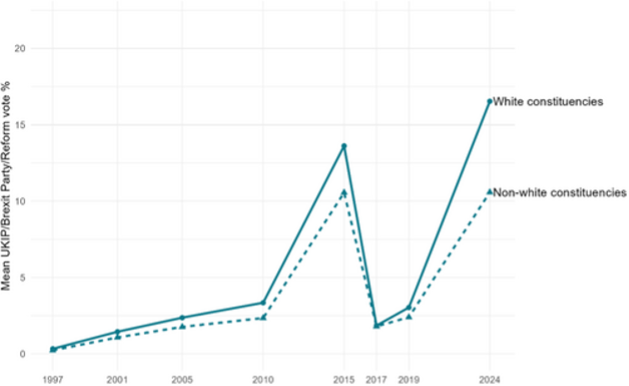

Another way in which support for UKIP was distinctive is the ethnic and age profile of its supporters, appealing to older, white voters. Figure 7 shows that UKIP in 2015 tended to be more popular in places with predominantly white populations than it was in more ethnically diverse constituencies, though the differences were comparatively modest. However, in 2024, these differences were somewhat more pronounced. Whereas in ethnically diverse constituencies Reform's vote is now at the same level as it was for UKIP in 2015, in predominantly white areas, Reform's vote now exceeds what UKIP obtained.

Figure 7: Support for Reform in white and ethnically diverse constituencies, 1997–2024

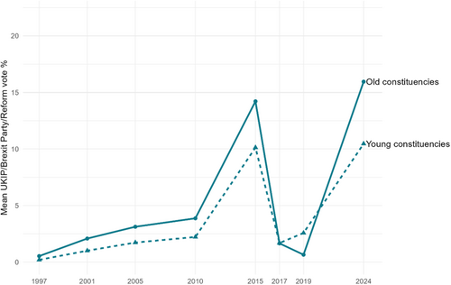

Similarly, Figure 8 shows that Reform's vote has increased more in constituencies with older populations than it has in constituencies with younger populations. Taken together, these findings indicate that Reform is building support in areas of prior strength rather than broadening its base, suggesting that social divides may be hardening rather than softening.

Figure 8: Support for Reform in older and younger constituencies, 1997–2024

Conclusion

The stability in the sources of support between UKIP and Reform implies that there is a strong—and relatively stable—base underpinning the party's electoral fortunes. There is little evidence that Reform’s base has expanded beyond UKIP but it has perhaps deepened, making the party a more credible and competitive electoral force. The Tories may not find it as easy to win back these votes as they hope.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley