| 8 mins read

As the twenty-fifth anniversary of the establishment of the devolved Scottish Parliament approaches, it can seem self-evident that the programme of constitutional reform pursued by the Labour government in the late 1990s has stoked support for independence and occasioned a historic political realignment in Scotland. The transformation of Scottish politics since the arrival of devolution has been stark and can be traced via the rise of the Scottish National Party (SNP); the parallel decline of Labour in Scotland; the debate that preceded the 2014 independence referendum; and the dominance of Scotland’s constitutional future in political culture.

Yet the lines of causation are still blurred. Certainly, it can be difficult to gauge whether the constitutional innovations of recent decades have themselves generated new commitments and identities, or if they have merely allowed for the clearer expression of political attitudes shaped by longer-term processes of social and economic change. There remain questions too as to the relationship between backing for the SNP at parliamentary elections and the broader movement in support of Scottish independence. Likewise, the case for independence appears to be in grave need of renewal. Lastly, the durability of the SNP’s electoral dominance is uncertain.

Devolution and the rise of the SNP

There was, from the outset, a basic tension present within the devolution settlement between acknowledging an already distinctive Scottish political culture and potentially providing the constitutional basis for further political divergence between Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom. At a fundamental level, the scheme detailed in the 1998 Scotland Act was retrospective in outlook, designed to address the political questions raised during the 1970s and 1980s.

Moreover, it is critical that the upturn in the SNP’s electoral fortunes prior to 2014 and the rise in support for Scottish independence recorded at the 2014 referendum are not conflated too crudely. The SNP was the beneficiary of fluctuations in the fortunes of other parties, especially falling support for Labour and the Liberal Democrats. It is, then, difficult to conclude that the SNP victories at 2007 and 2011 Holyrood elections pointed to any meaningful upsurge in support for Scottish independence.

Independence and the Scottish electorate

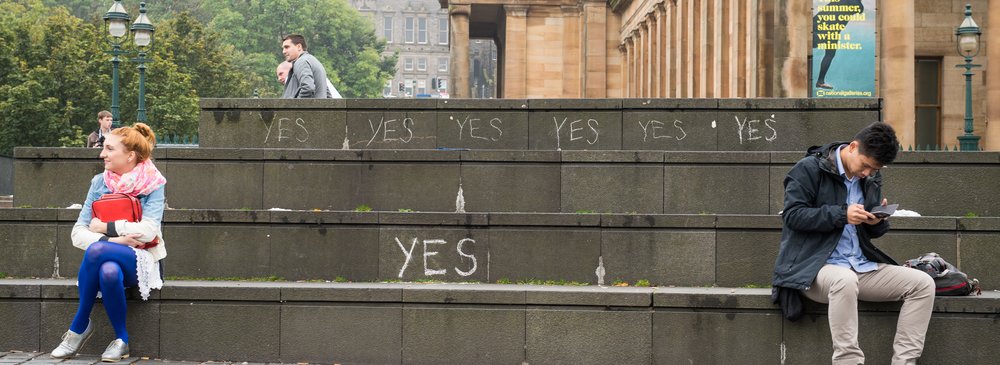

The 2014 independence referendum is, therefore, best understood as a discrete event as opposed to a logical extension of earlier political trends. For many, the referendum offered a unique opportunity to make the case for a more equal and just society, and to reject the policy of austerity being pursued by the UK government at the time. These arguments in favour of independence, which found their most receptive audiences in previously neglected working class communities, bore only the loosest, if any, relationship to the SNP’s official case. As the late Neil Davidson noted, that there had, in effect, been two separate pro-independence campaigns.

Some 85 per cent of Scottish voters took part in the referendum, a figure unmatched in the era of mass democracy, with 45 per cent of those who voted supporting independence. In the short term these voters swung behind the SNP, swelling the party’s membership, which rose to more than 100,000 in the referendum’s wake, and delivering the astonishing result at the 2015 UK general election, where, on a markedly increased turnout, the SNP secured almost 50 per cent of the popular vote in Scotland and gained fifty-six of Scotland’s fifty-nine seats at Westminster. Yet, while of immediate benefit, the influx of a younger, more radically inclined cohort into the party’s ranks also created difficulties for the SNP. It raised the possibility that more longstanding SNP voters would become alienated. With at least two distinct electorates, it seems doubtful whether in the long term the party can continue as the leading representative of both urban and rural Scotland.

The case for independence since 2014

The years after 2014 also saw the flaws in the SNP’s case for independence become increasingly apparent. Brexit complicated rather than confirmed the case for independence. In particular, the idea that Scots would continue be able to participate in a post-independence sterling currency union became frankly untenable. In addition, support for independence did not necessarily entail a pro-European outlook and polling suggested that around one in three SNP voters had actually voted in favour of leaving the EU.

More than this, the SNP has found no viable path to a second independence referendum, with the current UK government refusing to sanction another poll. Equally, Keir Starmer has overseen a reassertion of Labour’s historic antipathy towards the SNP. With the electoral route to a second referendum seemingly barred, and with the Supreme Court rejecting the legal argument that the Scottish Parliament can hold a referendum without consent from Westminster, some within the SNP have argued that elections should be treated as de facto referendums. However, Nicola Sturgeon’s successor as SNP leader, Humza Yousaf has already executed a retreat, suggesting that, should the SNP win a majority of Scottish seats at a general election, this would instead provide only the basis for further negotiations with the UK government on the holding of another referendum.

The failure of the SNP to identify a workable strategy for securing independence has been at the heart of the recent rifts that have developed within the independent movement. Indeed, the recent financial controversies that have dogged the SNP are also rooted, if only indirectly, in the absence of a coherent strategy on a second referendum.

Conclusion

There is, then, a feeling that the identities and divisions formed by the 2014 referendum and its aftermath have become exhausted. The ability of the SNP to hold together the mass support it attracted after 2014 appears to be waning. There are hints of a decoupling of the SNP vote and pro-independence sentiments. It is probable that, at the next general election, some of the pro-independence vote that has been largely, if not entirely, channelled by the SNP since 2015 will move across to the Labour Party, with the Greens offering a further option at Holyrood elections.

For all that support for Scottish independence increased during the 2014 campaign and has remained high since, there is no political vehicle or mechanism available to the independence movement to trigger a second independence referendum, and no sense of how to respond if a future Labour government reiterates the stance of the current Conservative administration and refuses to countenance a second independence referendum.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley