| 10 mins read

The new Labour government has placed increasing housing delivery at the heart of its agenda, linking two chronic problems: lacklustre economic performance and ever-increasing housing costs. The two elements are related. First, economic growth is held back by a lack of labour mobility as many people find it prohibitively expensive to move for work. Second, building significantly more homes would provide economic growth, not only through an expansion of the construction industry, but also through an expansion of consumer spending as people establish new households.

The new government has strongly linked the intention to deliver more homes to reform of the planning system, which is seen as a key barrier. The call for planning reform is a rite of passage for incoming governments. There have been many reforms of the system since at least the 1980s, and none have led to the production of housing at the scale required.

Will things be any different under this government?

The government must oversee the development of 300,000 housing units per annum to achieve its 1.5 million new homes in England by the end of the parliament (planning is a devolved competency across the UK). Between 1992 and 2024, annual housing delivery peaked at approximately 250,000 units for just two years. The 1.5 million figure feeds through to huge changes in housing targets for some local authorities. For example, the London Borough of Bromley delivered an average of 229 housing units per year between 2021–22 and 2023–24, significantly below its target of 774 units per annum. an indicative new housing target (arising from a new method of calculating housing need), is 3,001 units.

Similarly, in Hertsmere, an average of 185 units were delivered per year against a target of 760 units. The indicative target is 1,034 units per annum. These changes are far from exceptional.

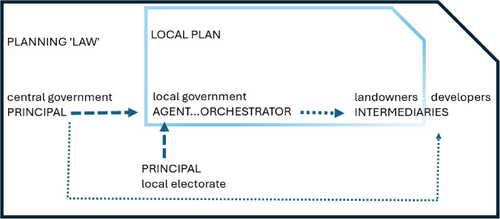

The identification of a possible solution can be viewed as an example of the principal-agent (P-A) challenge. Having decided to delegate planning decisions to local authorities as agents, how does central government, as a principal, ensure that its agents do what it wants?

Even where local authorities are willing agents, they do not own much of the land that will be built on, and they do not develop much, if any, housing themselves. They are orchestrators who must work with landowners and developers as intermediaries. The orchestrator-intermediary (O-I) relationship requires an orchestrator to support and encourage an intermediary to cooperate. The local authority must facilitate and encourage private sector landowners to sell, and developers to bring forward schemes. However, the latitude they have depends on the planning system, which is managed by the principal. Central government, as principal, needs to manage both the P–A relationship and to implement systemic changes that give agents greater scope as orchestrators, enabling them to facilitate and encourage landowners and developers (intermediaries).

We employ the P-A and the O-I perspectives to evaluate the government's approach, focusing on the government's approach to green belt land.

Housing delivery as a principal-agent challenge

Local authorities are required to produce a local plan, which, guided by the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), sets out land use policies for a local area for an approximately fifteen-year period, although the local plan will be subject to updates. The NPPF requires local authorities to identify and maintain a five-year supply of land, based on an assessment of housing need that is achieved through the application of a government-approved method (the ‘standard method’).

The Starmer government tightened the P-A relationship and reinforce central oversight. Targets have now been restored as mandatory and a series of measures and sanctions incentivise local authority compliance. Among these is the requirement for a five-year land supply to include a ‘buffer’, intended to give developers greater flexibility and thereby improve the likelihood that housing targets will be met. Crucially, the size of the buffer functions as a sanction: the greater the shortfall in housing delivery, the larger the buffer imposed.

Where an authority is far from its target, the default for deciding applications switches to being in favour of the development. It becomes harder for a local authority to refuse planning applications. However, the more control the principal exerts, the less independent the agent becomes, thereby undermining the very rationale for delegation. A further example of the current government seeking to tighten the P-A relationship is a proposal to reduce the involvement of local elected members.

In summary, while the effects of the government seeking to amend the P-A relationship remain to be seen, the system's inherent flexibility remains, which leaves scope for ‘unwilling’ agents to slow housing delivery and for other bodies challenge applications.

Orchestrators and intermediaries

Unlike landowners, whose land is fixed within the jurisdiction of a local plan, developers can choose where they develop (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Housing delivery as a principal-agent, orchestrator-intermediary challenge

An important point is that in the case of housing, the government as principal is involved in a direct relationship with agents, but it also sets the context in which intermediaries will consider progressing development. Through national planning law, the principal sets the context in which orchestrators can seek to incentivise and support the intermediaries. This interaction between principal, agent and intermediary is illustrated through measures set out in the NPPF to address the under-delivery of housing. These sanctions target agents (punitively) and intermediaries (positively); they make failure unpalatable for agents as they reduce the power of the agent to manage housing delivery in the way it prefers.

A radical approach would be to expand exponentially the supply of land by rolling back planning policies, allowing market mechanisms greater freedom to operate. At a basic level, this is the principle behind the buffer. Developers might then be seen more as orchestrators working with intermediaries (landowners, builders and so on) to develop housing. However, the government has not indicated any desire to make such a fundamental change.

Green belts, agents and intermediaries

Green belts limit the outward growth of urban areas by stopping them from merging into one another. Numerous academic studies and reports have argued for green belt reform. The green belt prioritises the use of previously developed land, which is simply not sufficient to meet housing need.

The strategic release of selected parts of the green belt to maximise the potential for public transport-related growth could be a solution. Advocates argue that a relatively small proportion of green belt land would be lost relative to housing gained.

The current government have started to use the term ‘grey belt,’ indicating a direction of travel. An enhanced requirement to review the green belt, where land cannot otherwise be identified for housing, may act as a spur to bring forward more land.

Local government must balance its regulatory power to enforce planning standards, including affordable housing requirements and sustainability criteria, with the need to keep developers engaged in delivering housing. Much of the regulatory scope is determined by the principal and potentially ties the hands of the agents.

The P-A relationship does not allow enough flexibility to the agent once in their orchestrator role. Nor do the changes made by the principal signal a sufficient shift in the planning system to the intermediaries. Overall, the retention of green belt policy ‘as is’ does not signal a significant change in land supply.

Conclusion

The changes to green belt policy indicate a clear intent to shift the P-A relationship by reducing agents’ ability to use green belt policy to frustrate housing delivery. The green belt is now ‘less off limits’ than it was previously. Any electoral costs are likely to be limited, given voting patterns: green belt constituencies tend not to vote Labour.

However, to be effective, even a willing agent must successfully negotiate with and encourage landowners and developers, an orchestrator-intermediary relationship. The ongoing challenge will be to enable agents to balance multiple expectations through planning, while also incentivising intermediaries.

Digested read of a longer journal article created by Anya Pearson in collaboration with the authors.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley