| 6 mins read

There is widespread concern about a crisis of trust in society, government, and the world. The UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, summed up the mood in a speech delivered last year: “Trust is at a breaking point. Trust in national institutions. Trust among states. Trust in the rules-based global order. Within countries, people are losing faith in political establishments, polarization is on the rise and populism is on the march.”

But if trust falls, is this always a bad thing? Our new ‘TrustGov’ research project seeks to challenge the conventional view. In a so-called post-truth age, surely it should be recognised when people, leaders and institutions are actually untrustworthy?

A crisis of trust only exists if people trust when they should not – or if they do not trust when they should. We need to get beyond lamenting low or falling trust and ask instead whether trust is justified by trustworthiness.

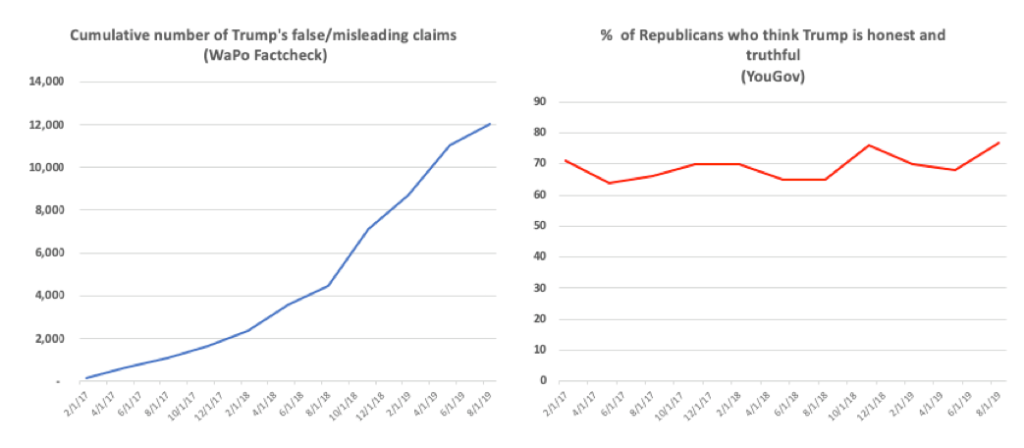

These judgments can easily be incorrect for all sorts of reasons. To give a simple example, the Washington Post’s Fact Checker reports that since assuming office, President Trump has made over 12,000 false or misleading claims.Sharpie-gate is only the latest. Despite this, as Figure 1 shows, a recent Economist/YouGov poll found that three-quarters of Republicans say they believe that Donald Trump is honest and trustworthy and the line is pretty flat.

Figure 1

A trust judgement is a tricky decision, especially where we have only limited and partial information, such as in judging the working of Washington DC, Westminster, or Brussels. We make judgements mixing affective or emotional leaps of faith, alongside a reasoned and updated judgement of performance based on evidence. We may ask: Are politicians corrupt? Do they deliver things I want? Do politicians care about people like me?

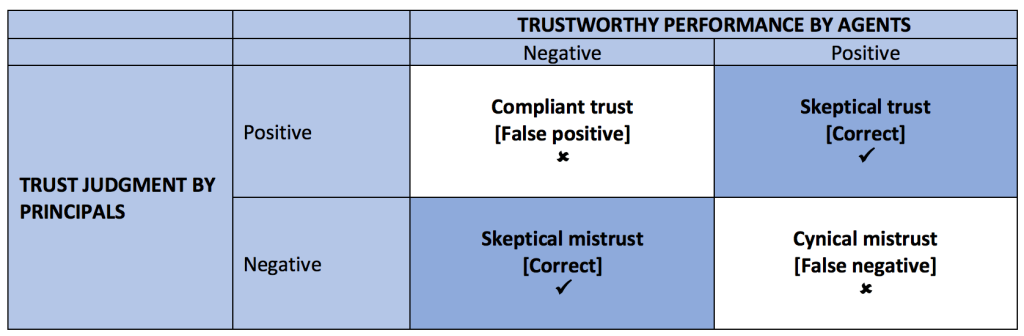

The reasoned part of that judgement fascinates us. Can citizens come to a correct judgement about whether to trust? Figure 2 depicts the options.

People can either trust or not and the agent can be worthy of that trust or not. This dynamic generates four categories. People can correctly judge that the political system is trustworthy (skeptical trust). They can instead judge correctly that it is untrustworthy (skeptical mistrust). However, the sense of crisis in trust should be focused on the top-left and bottom-right quadrants: People trusting when they should not (compliant trust). People not trusting when they should (cynical mistrust).

Figure 2: Typology of Trust judgments

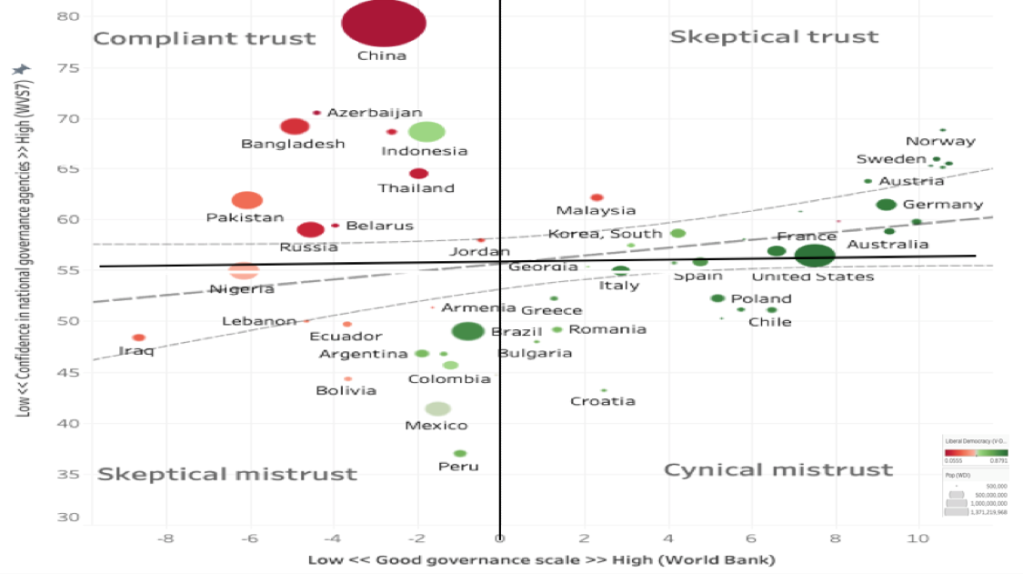

The TrustGov project has begun to explore trust along these lines. Figure 3 illustrates some broad-brush national comparisons using new data in almost 60 societies worldwide. We used a simple formula. A measure of public confidence in national political institutions from the World Values/European Values Survey 2017-19 is compared against a measure of the quality of governance in those countries using the World Bank’s estimates (WBI).

Figure 3: Comparing Types of Trust Judgements. Sources: The WVS/EVS Wave 7 (2017-2019), 58 societies (n.91,145); the Quality of Government dataset (Jan 2019). Note that trust in core agencies of national governance is measured by a standardised 100-point

Societies in the top right quadrant of Figure 3 see a strong correlation between trust and performance, suggesting skeptical trust judgments, including many Nordic and Northern European nations led by Norway and Sweden.

The societies in the bottom left quadrant also show that public confidence in national political institutions is largely consistent with the WBI indicators of good governance, reflecting skeptical mistrust; exemplified by cases such as Iraq, Mexico and Peru.

The public living in the societies located in the top left quadrant, such as China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Belarus and Russia, express greater confidence and trust in their government than the WBI estimates suggest is justified by the good governance indicators. This encapsulates our concept of compliant trust.

Finally, people living in the nations located in the bottom right quadrant express less trust in their government that the good government indices suggest is warranted, indicating a stance of cynical mistrust.

The United States is often thought exceptional but in our comparison it proves a mix, close to Australia and France, divided on the line between skeptical trusters and cynical mistrusters.

There is still a lot to explore. Would countries move around the four quadrants if we focus more on policy performance, such as the delivery of economic growth? It would seem likely that many would. Do we understand how citizens come to trust judgements and balance out various factors? Well no, and we need to understand that process much more. A country-by-country comparison should not lead us to neglect the differences within countries and ask about the location of social groups, like differences by age, sex, education, party support, and media use. And can similar distinctions be observed for social trust among peoples and international trust among states?

For now, our claim is that in exploring trust, the key question is not whether trust is in freefall or not (where there remains debate). The question that matters is whether people can make trust judgements that match the reality of the context they are in. Given the complexity of modern society and its interdependence, people need to trust -- but it would be in their interests to trust correctly.