| 7 mins read

Recent decades have seen major shifts in the demographic and geographic basis of party support. A less discussed, but equally crucial trend was the divergence over two decades of voting behaviour between those identifying as English (or more English than British) and the (more) British. Between 2001 and 2019, the Conservative share of ‘more English than British’ voters rose from 40% to 68% while ‘more British’ voters still preferred to vote Labour. ‘Political Englishness’ was also evident in support for UKIP and the Brexit party in the 2014 and 2019 EU elections and in support for Leave in the EU referendum.

What makes national identity politically important?

Our general answer is that national identity may reflect the social structure of a nation when different life experiences and values become associated with ideas of Englishness or Britishness. It may also carry understandings of the nation beyond shared values and demography. Both may be politically mobilised under the right circumstance.

We argue that, combined with political events and strategies, specific patterns and trends in public opinion set the stage for the realignment of voters by national identity.

Analysing twenty years of polling on public opinion data, values and demographics, we find that the ‘more English’ were consistently the most socially conservative and more concerned about immigration. They were older and educated to a lower level and were less diverse than the ‘more British’. We also see significant divergences in values and attitudes: the ‘more British’ became sharply more liberal, the higher education gap widened, and their ethnic diversity increased dramatically, although there was little difference or divergence on economic values.

The broad electoral trends reflect these differences and divergences, but neither are sufficient to explain the extent of the changes or the switching between parties by English voters. Polling data consistently shows that that ‘more English voters’ are more Eurosceptic, identified Brexit with English national interests, want to protect English interests within the UK and to strengthen English national democracy. We suggest that ‘political Englishness’ was manifest when political choices created links between the demographics, socially conservative values and immigration concerns of English voters and their ideas of the nation, sovereignty, democracy, and EU membership.

A combination of national sovereignty with concern about immigration was a common feature in ‘more English’ support for UKIP and the Brexit Party, the EU referendum and the Conservatives’ 2019 ‘Get Brexit Done’ general election victory. The Conservative Party made explicit appeals to ideas of the English nation in introducing English Votes for English Laws and in their successful 2015 warnings about SNP influence on a minority Labour government.

Political Englishness’ legacy is evident in the mutation of comparatively socially liberal and pro-EU Cameronite conservatism into a steadfastly Eurosceptic and socially conservative party, and Labour’s rejection of re-joining the EU. But a crucial question is whether the politics of national identity will shape the outcome of the next election.

Exclusive new data from YouGov for the Centre for English Identity and Politics offers strong indications that national identity continues to shape the political landscape, but with more limited impact as less polarising issues gain salience.

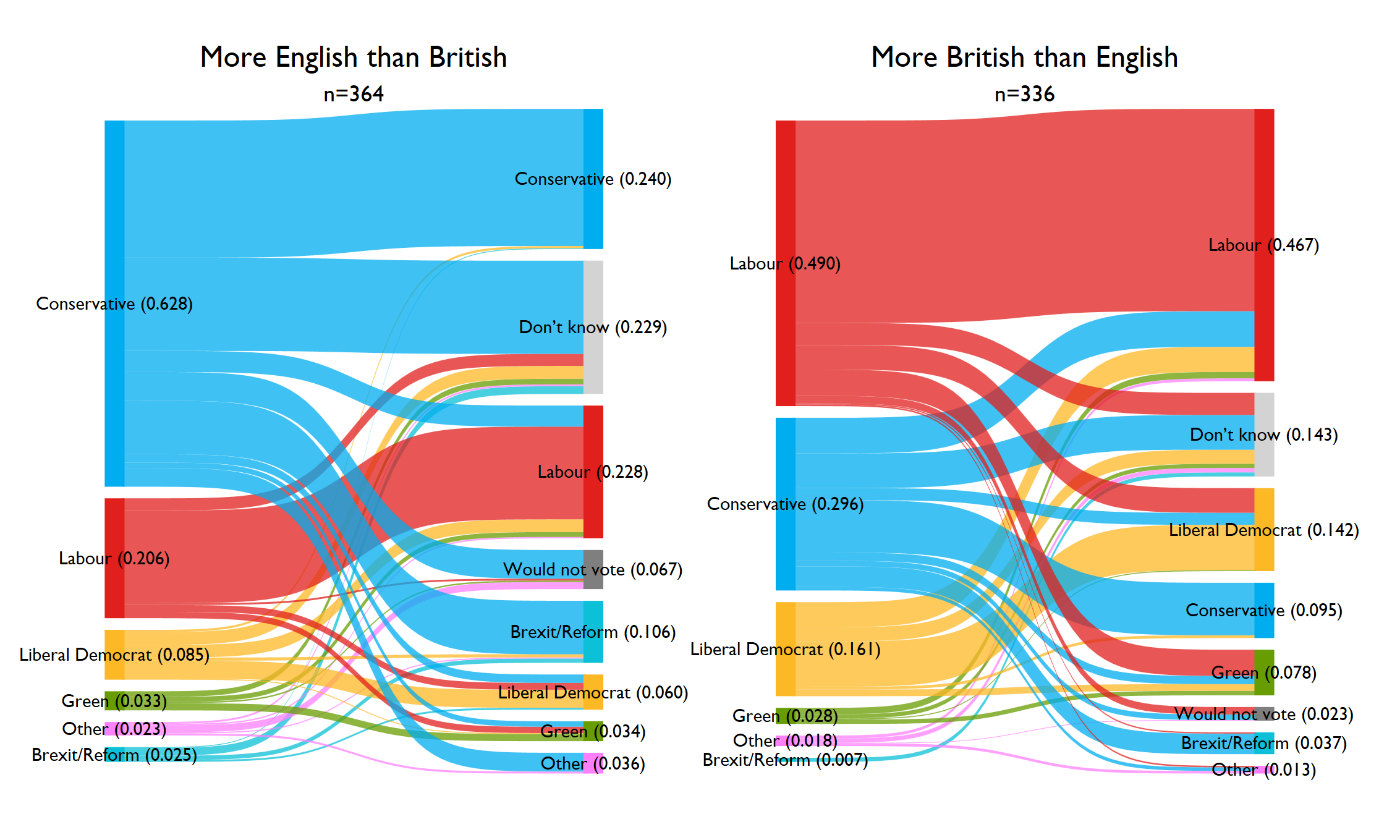

The diagram below shows how people who voted in 2019 said they would vote in a June 2023 survey, separated by their expressed national identity. The height of the bars and numbers in brackets represent vote share (left of each diagram: 2019 general election, right: June 2023 survey). The thickness of the connecting line represents the share of voters formerly supporting party A who later support party A, B, and so on (or who say ‘don’t know’ or ‘would not vote’).

Figure 1. Vote switching by national identity, 2019 general election -> June 2023 (YouGov survey for the Centre for English Identity and Politics). Proportions as fractions (e.g. 50% = 0.5)

The Conservative lead among the More English has been all but eliminated (falling from 63% to 24%), and their weak position among the More British has fallen further placing them behind the Liberal Democrats among this group. In absolute terms, the Conservatives lose more from the More English, but proportionately they retain fewer of their 2019 More British voters (30%) than More English (37%), and the most electorally lethal switching for the Conservatives (direct switching to Labour) is higher among the More British.

The flow towards minor parties (who currently poll well above their 2019 results) is clearly structured by identity. The Greens are the chief beneficiary of switching among the More British (mostly Lab-Green movement), but Reform (formerly Brexit) poll decently with the More English, with almost all their gains from the Conservatives.

We also see a high degree of political ‘homelessness’ among the More English. Nearly one in four say they do not know how they would vote (against one in seven of the More British), and a small but substantial portion may exit the electorate entirely: 7% of More English say they would not vote, against 2% of More British.

In 2019 the Conservatives recovered from the loss of the June EU election to victory in December’s general election on the votes of the ‘More English’. Could a Sunak-led Conservative party repeat the trick?

‘More English’ Conservatives have largely drifted towards Reform and ‘Don’t Know’ rather than Labour, and there may be some mileage in priming ‘wedge issues’ such as Brexit, immigration, culture war debates and warning of SNP influence over a Labour minority government.

But much has changed since 2019. Brexit is perceived to be going badly and government handling of immigration is seen as disastrous. Labour savvily positions itself on these and most ‘culture war’ issues to avoid alienating authoritarian-minded voters, while Conservative campaign rhetoric might land poorly with an electorate that is generally liberalizing. At the same time, national identities do not polarise on economic values, making the high cost of living comfortable territory for Labour. However, should a Labour government be elected, it will have to carefully navigate the key concerns of the ‘politically English’ to build an enduring coalition.