| 8 mins read

The 2024 General Election was an election of so many historic records that one more simply went unnoticed–a record number of ethnic minority MPs was elected. According to some early calculations, on 4 July, ninety candidates of ethnic minority backgrounds were elected, up from sixty-six in 2019. This amounts to almost 14 per cent of the House of Commons. It is likely that the British Parliament is now for the first time—fully numerically representative. This is something to celebrate, and has happened much faster than expected.

While it seems ethnic minority politicians face fewer barriers to entry than twenty years ago, is it possible that ethnicity simply does not matter at all?

Traditionally, there are two ways in which the race and ethnicity of politicians might impact their electoral fortunes (in this article, ethnicity and race are employed interchangeably). One is the discrimination in the selection process. The other is of course voters.

Candidate selection

While not all parties reliably use ethnicity quotas for their shortlists, clearly all major parties are now putting much more effort into not just increasing numbers of minority candidates, but into improving the winnability of seats for which they are selected.

In the past, either candidates from ethnic minorities weren’t selected at all or they were selected in uncompetitive seats with no hope of being elected. But when the Conservative Party saw an opportunity to detoxify its ‘nasty party’ reputation by diversifying its politicians, minority candidates became over-represented in safe seats. In the face of their terrible 2024 result overall, the Conservatives emerged more diverse in percentage terms, rising from 6 per cent to 11 per cent of the PCP.

Unlike the Conservative Party, Labour has used various ethnicity requirements for shortlists in some previous elections. Labour's progress has been so impressive that the Labour minority MPs elected in 2024 are on a par with the number of all minority MPs sitting in the previous Parliament. What is more impressive is that 2024 also saw a significant rise in numbers of ethnic minority Liberal Democrat MPs, though the party has historically lagged behind both main parties.

It is difficult to argue that ethnicity is still a major obstacle to elected office from the point of view of party selection in the UK's main parties.

Co-ethnicity advantage

With so many minority politicians no longer voted in by minority voters, there is no longer much electoral advantage for them to represent their group descriptively. Ethnic minorities in the UK are an extremely diverse group in terms of their ethnicity, religion and other demographics. Taking Rishi Sunak as an example, it is unlikely that they have all had more positive feelings towards him. British Indians—are historically generally better off in terms of social class and racial disadvantages. It is likely that Indian-origin voters will be more positive about Sunak than voters of other ethnic origins.

The second reason why not all minorities will approve Sunak is because of the position towards race equality that Sunak himself—and through the position of his political party—has been identified with. Ethnic minority voters who subscribe to colour-blind ideology will also be more positive about Sunak than those who still support more anti-racism protections and believe widespread prejudice is still present in British society.

Disadvantage from White majority voters

The other side of the coin in terms of any advantages minority candidates may get from minority ethnic voters is of course any disadvantage they may suffer from the (more numerous) White majority voters. Some White majority voters bear some resentment towards Sunak based on his ethnicity, but that it is limited to those with ethnocentric attitudes. Both his party and his Cabinet have made it clear on many occasions that they believe racial disadvantage is not a systemic and institutional problem and have, by and large, disavowed multiculturalism as divisive. Therefore, if voters who share these ideological positions still show bias against Sunak, it is clear this would be as a result of their prejudice against his ethnic origin and not a matter of policy.

However, the second possibility is that ethnic minority candidates are no longer solely minority representatives, but simply politicians, and do not receive any ethnic penalty. Given the number of MPs of minority origin and experimental evidence on the whole showing that voters do not discriminate significantly against non-White candidates, this seems likely.

Who liked Rishi Sunak?

The British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP), conducted just before the 2024 election, is nationally representative, but it is not representative of ethnic minority voters, making it tricky to use to compare White majority with ethnic minority voters. However, it is the only publicly available survey with large enough numbers.

Specifically, there are three relevant attitudinal questions. The first one measures opinions on one of the fundamental principles of multiculturalism: whether equal opportunity rights for Black and Asian minorities have gone ‘too far’ or ‘not far enough’. The other two are items sometimes included in racial resentment scales: perception that there is a lot of discrimination in favour of or against ethnic minority people and against White people.

The British Election Study survey contains three questions on attitudes towards the then-PM: whether respondents liked Sunak, whether they felt he was competent and whether they believed he had integrity.

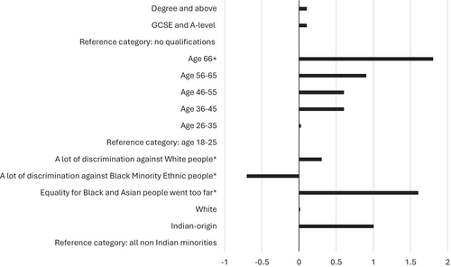

Figure 1 shows the most influential predictors of liking Sunak.

Impact of voter characteristics and attitudes on liking Rishi Sunak. *Effect size shown in figure is for moving from one extreme of the scale to another. Source: British Election Study Internet Panel. All data weighted using the weights provided.

Crucially, Sunak did not seem to incur a negative penalty from White voters, who disliked him as much as ethnic minority voters other than British Indians. Older voters liked him a lot more. Racial attitudes, as expected, mattered hugely to whether Sunak was liked or not, but not in the direction envisaged. Ethnocentric White voters were much more positive towards Sunak.

The two racial resentment measures worked in similar ways: those voters who felt that there was now discrimination against White people were more positive about Sunak and those who believed there was a lot of discrimination against Black and Asian people disliked him more.

Attitudes to ethnicity matter to voters, but not the ethnicity of politicians

Voters clearly still care about ethnicity, but not in the ways usually assumed.

For White voters, their dislike of multiculturalism and racial resentment led to higher approvals of Sunak, very much in line with his own lukewarm stance towards multiculturalism and his colour-blind ideology. With the severing of the link between ethnic minority politicians and ethnic minority voters—as well as with left-wing parties—more politicians of non-White origins have now emerged on the racially conservative right.

It is worth remembering that some voters’ continuing prejudice against them might have an important impact on their lives in the form of social media abuse and threats of violence, for example.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley