| 10 mins read

Political finance regulation in the UK is known to be flawed. While donations to political parties and candidates above certain thresholds are regularly published, there are concerns about the amount of influence super-rich donors can exert over the political process, and the potential influence of foreign individuals. The spectre of Elon Musk allegedly considering a £80 million donation to the Reform Party raised legitimate questions about whether there should be a cap on how much one individual or organisation could donate to a party and whether rules need amending to prevent foreign individuals from exerting their influence by donating to UK parties.

Despite these deficiencies, one supposed redeeming feature of the UK's political finance regime is transparency. Since 2000, political parties have had to declare all significant donations every quarter and more regularly during a general election campaign. Two standard sources of information are the register of interests for MPs, administered by the parliamentary authorities, and the public record of donations and party accounts, administered by the Electoral Commission. In both cases, there are minimum sums below which donations do not need to be reported and/or published.

By themselves, the transparency requirements do not remove the possibility of corruption. However, it means that, even if a small group of the super wealthy receive undue access to decision makers, in theory (at least) we can see who they are.

It is usually considered that these two sources are comprehensive records. However, there is another—completely legal—source of donations that falls outside these transparency requirements. It is, in effect, a hidden source of money.

During the ‘short campaign’ of a general election (and other types of elections, too) donations can be made directly to individual candidates without their details being routinely published. In some ways, the loophole is worse for local elections.

Whilst these donations are recorded on candidates’ constituency spending returns (which are filed with the relevant local authority and subsequently the Electoral Commission), only the aggregated amount of donations declared by candidates gets published by the Electoral Commission. This means that there is no publicly available record of who is funding individuals’ election campaigns.

As we show in our analysis, the total amount of ‘missing’ donations is likely to run into millions of pounds. How does this happen, and what are the possible solutions?

Donations via the ‘back door’?

The Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA) formally recognised political parties for the first time, introducing restrictions on who can legally donate and a public register of donations above a certain threshold, maintained by the Electoral Commission. In addition, the legislation capped the amount parties could spend nationally at general elections. This ushered in a new era of transparency, although at the same time the amounts donated to political parties rose by 250% between 2001 and 2021, with a large increase in the proportion coming from ‘super-donors’ contributing more than £100,000 each.

Now that donations above the value of £7,500 to political parties are reported quarterly, donors who wish to remain low profile or unnoticed have a greater incentive to donate directly to a candidate's election campaign. Further, there is an incentive for political parties to encourage this.

There has been very little analysis of the sources of income declared on these candidate returns. This may be owing to the assumption that candidates simply declare that they received their campaign funds from a unit of their party.

Indeed, at the 2019 election, 141 candidates declared more in donations than the legal limit for spending on their constituency campaign, based on our calculations from Electoral Commission data. This number is on the rise: fifty-three candidates did the same at the 2015 election, whilst 170 candidates did so at the 2024 general election.

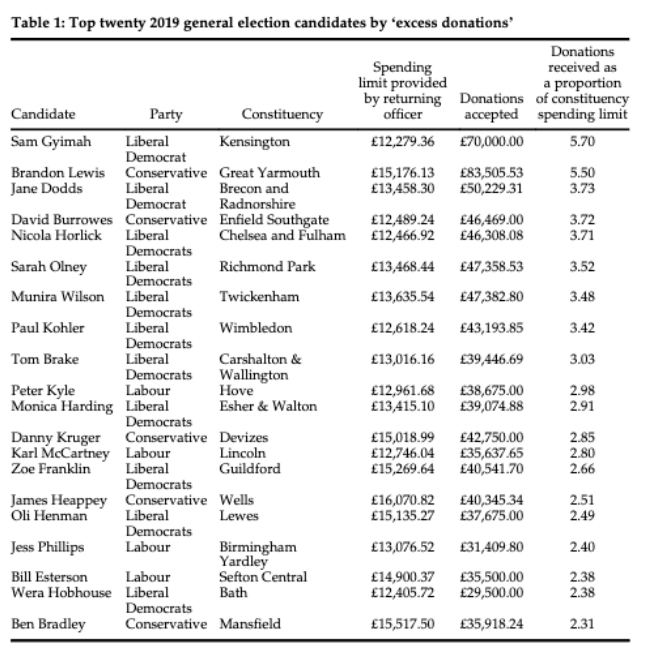

Table 1 lists the top twenty candidates at the 2019 general election in terms of the amount of donations received proportional to their constituency spending limit.

Table 1. Top twenty 2019 general election candidates by ‘excess donations’

Why would candidates raise more money than they can legally spend on the ‘constituency’ campaign? A likely explanation is that there is expenditure that can be legally made which need not count against the constituency limit. In particular, a candidate may raise funds that are then used to pay for campaigning which counts against their party's national expense limit, but which is for activity targeted at their constituency.

It is also possible that parties encourage donors to give directly to candidates rather than to the party in general to avoid the publicity, but that at least some of the money is later transferred to the party. An alternative explanation is that candidates may use any surplus funds post-election.

How much money is donated this way?

We asked the Electoral Commission to provide us with the detail of donations from a sample of candidate returns at the 2019 election. We analysed donations received on ninety spending returns.

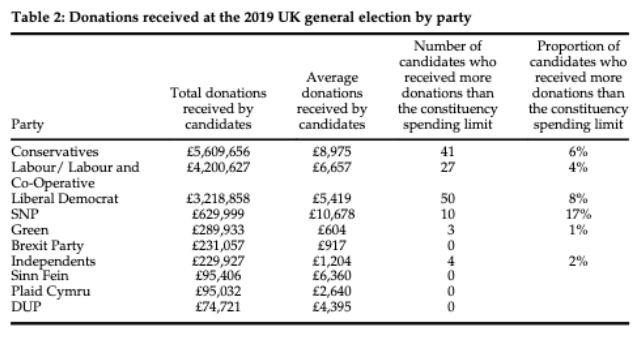

Table 2 shows the amount of donations to candidates at the 2019 general election by party (for totals over £70,000) and the number and proportion of candidates per party who received more than the declared amount.

Table 2. Donations received at the 2019 UK general election by party

In total, £1,380,117 of donations exceeding the constituency spending limits was received by candidates at the 2019 election. By 2024, this had risen to £1,999,929. What happens to the surplus seems to be unresearched; nearly £2 million of donations in effect ‘go missing’ every election.

In total, our sample of ninety candidates declared donations just shy of £1.7 million. Of this, £758,000—45 per cent—constituted donations from individuals or organisations other than a unit of the candidate's political party.

In a random sample of thirty-seven MPs, we found that a significant 23 per cent of their declared income came from individual donations. If we extrapolate this figure we can assume that successful candidates received £1.66 million in the 2019 general election, and £1.78 million was donated to unsuccessful candidates–a total of over £3.4 million.

There is a significant public interest in being able to identify the sources of this money and to check whether such donors are receiving access or favours.

Improving transparency

In stark contrast to the transparency principles of PPERA, the limited data provided to us by the Electoral Commission was so heavily redacted for GDPR purposes that we were not able to identify individual donor names.

The only way we were able to identify some of the donors to candidates at the 2019 general election was to cross check the individual amounts received by candidates who did get elected against the House of Commons’ register of MPs’ financial interests.

In total, we identified seventy-three donations to twenty-two MPs, of amounts totalling more than £1,500, which should have been declared on subsequent MPs’ registers of interests. If our sample is representative, it means that 11 per cent of MP campaign donations are not being declared.

Potential regulatory reform

There are three straightforward steps, none of which require legislation or significant

new resources, that would allow the disinfecting sunlight to shine on donations made directly to candidates during the short campaign:

- For the Electoral Commission to revise its decision to redact the names of donors when it releases copies of constituency election expense returns.

- For the Electoral Commission to include in its analysis of political finances the totals of ‘new’ donations and to consider including such donations as an annex to its public record of donations.

- For the Electoral Commission and the parliamentary authorities to liaise after each election to identify those donations recorded in expense returns and which Members of Parliament have failed to include on their register of interests.

We believe that there is a strong public interest in these reforms. This is arguably the most significant source of failure to declare donations in the British system.

These findings therefore should provide a further impetus for change, both to improve transparency of political finance and to improve the data about how our elections work, upon which regulators, legislators and academics all depend.

Digested read produced by Anya Pearson in collaboration with the authors.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley