| 9 mins read

The UK is a spatially unequal nation. Improving economic performance and opportunity outside of the capital and its surroundings remains a significant long-term policy challenge that is holding the UK back, both economically and politically.

Regional inequalities have also become a remarkably salient issue to voters. In 2021, polling found that British citizens believed inequalities between more and less deprived areas were the most ‘serious’ facing the nation.

The previous government's ‘Levelling Up’ agenda attempted to speak to this issue. Labour's 2024 election victory saw the slogan dropped, but they committed to ‘building a stronger economy in all parts of the country’, pledged to address health inequalities between regions and proposed transport improvement for the North of England. Moving away from a model that is over reliant on the over-performance of one sector or one corner of the nation is needed to deliver the government's number one ‘mission’ of kickstarting economic growth.

But it would be a mistake to view this as a case of ‘London versus the rest’. Firstly, because inequalities within the capital itself are also substantial. Secondly, despite ‘rich London’ stereotypes, the capital's housing crisis means that all but the most affluent Londoners are in some ways worse off than their counterparts elsewhere. Finally, and crucially, the city's housing crisis is also holding back London's economic performance. Given the scale of the capital's contribution to the national economy, its housing is therefore an issue of national importance.

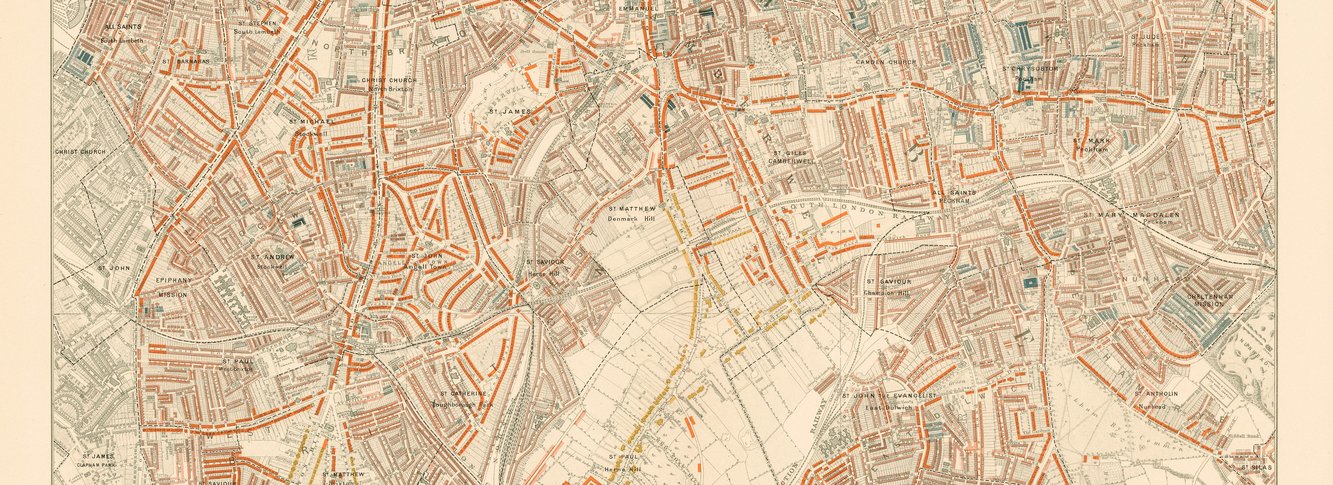

London and spatial inequality

‘Rich London’ irrefutably exists. London is home to the majority of the UK's billionaires and millionaires. Taxes generated by parts of London's economy fund public services and investment across the rest of the nation. Without the capital, the country would currently be unable to finance itself.

However, London is also a place of extreme poverty and great intra-regional inequality. Its poverty rate is the worst in the country. Around a third of London's children grow up in poverty. In 2018, the Resolution Foundation found the average London household had a lower income than the average UK household, after housing costs were factored in. The ‘London deal’ of higher average incomes mitigating higher average housing costs is failing. This leaves most Londoners worse off financially than their counterparts elsewhere in the UK.

Housing, inequality and London

Households in poverty in London spend an average of 54 per cent of their income on housing; in the rest of England, the average is 32 per cent. In October 2024, there were more than 323,000 London households on the waiting list for social housing. Rough sleeping has also increased three times over in London since 2008/9. There are significant housing quality issues across the capital.

The Greater London Authority (GLA) has also found that housing affordability is directly connected to a sizeable negative impact on productivity. Londoners have the longest average commutes in the country, report lower levels of life satisfaction and happiness, and higher levels of anxiety, than the national average. Failure to resolve London's housing crisis could undermine the appeal of the city as a place for highly skilled, highly mobile global talent.

Why a London problem?

London's housing crisis is an important national economic issue, but the electoral salience of other parts of the UK, including the so-called ‘red wall’ in the North of England, incentivises parties to prioritise the needs of voters outside of the capital.

Londoners have different concerns to voters elsewhere. In the build up to the 2024 election, housing came sixth in a national poll of voters’ overall priorities. This contrasts with housing affordability and the cost of living coming top as issues of concern for Londoners.

So why is it so hard to solve the capital's housing challenges?

Political panaceas

In response to the varied, if ultimately failed, approaches of London mayors to raising the supply of housing in the city to meet the level of demand, a variety of panacea-like solutions have been heralded across the political spectrum.

The accusation that brownfield land was not being properly utilised by the mayor was one of many thrown in the long battle between Sadiq Khan and central government during the Conservative years. However, there simply is not enough viable brownfield land available.

Labour has attempted reclassifying much unappealing green belt land as ‘grey belt’. But there is also simply not enough of this to deliver all the homes that London needs. Planning reform to release land more quickly and target building more effectively is undoubtedly important, but could lead to further stockpiling of valuable land rather than a wave of new building. We must genuinely transform the way sites are appraised, allocated and developed. Ambitious measures, such as new towns, are essential, even if their delivery will likely bring significant backlash.

National policy for London housing

The impacts of external shocks, from the global financial crisis, central government austerity and reform, Covid-19 and the inflation related to the Ukraine War were hugely significant. The limited nature of mayoral housing powers, alongside the fact that mayors are prohibited from raising, retaining and spending most significant taxes at a city-wide level has also limited the ability of successive mayors to act directly to solve the housing crisis. Given this, central government is ultimately the most important actor in solving the crisis in London.

With reformist zeal, Labour have pledged to deliver 1.5 million homes by the end of the parliament and have made planning reform a key area of focus. Alongside this, the Starmer government are promising a comprehensive reorganisation of local government and a significant overhaul of the role of institutional finance in driving economic growth—all in the calendar year 2025.

Devolution and strategic planning

The combination of the new planning legislation and the English Devolution Bill herald a return to strategic planning across the country, with the new ‘strategic authorities’—either mayoral combined authorities or combined county authorities—tasked with strategic spatial planning to overlay the local plans of their constituent councils.

Housing targets in London's surrounding local authorities must properly reflect their deep economic ties to the city, and their strategic spatial plans must be considered as complementary to the London Plan.

Financing development

A combination of social housing capital funding and institutional investment could accelerate the delivery of homes. On the developer side, contributions from the construction sector should also be factored into strategic planning, particularly given the potential for planning reform to de-risk elements of the process and increase the stability of investment. Section 106 and social value contributions can help to provide the basis of new infrastructure for housing, particularly when considered at scale.

Skills, labour and capacity

A lack of skilled labour stands as a major impediment. This is where another of the government's reforms, the establishment of Skills England, must be brought in. A London-wide upskilling plan for construction and development required, to supplement the GLA's Skills Roadmap.

London's housing crisis is a key driver of poverty in the capital. By holding back productivity in London's economy, it is also a handbrake on growth at a national level. It is extremely difficult to solve, but following decades of failure, it must be treated as a national priority.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley