| 7 mins read

In the run up to the 2024 general election, Labour leader Keir Starmer called ‘wealth creation’ Labour's ‘number one mission’. Entrepreneurial-driven wealth creation that boosts innovation, builds infrastructure and brings more productive business methods is vital for prosperity. But the concept is a slippery one.

In the UK, the ratio of private wealth to national output has risen from three in 1970 to almost seven in 2020, with similar climbs in other rich nations. According to Forbes, the number of global dollar billionaires increased from 587 in 2005 to 2781 in 2024—a more than fivefold increase. This exclusive club holds wealth estimated at $14.2 trillion, some 14 per cent of global output.

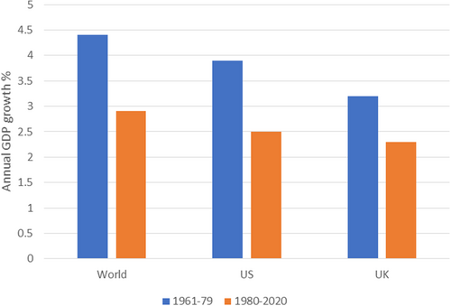

So, has this sustained wealth boom been good or bad news for economies and the rest of society? Rates of investment, productivity growth and innovation were higher in the postwar decades when personal fortunes grew more slowly. Since the 1980s, the reverse is true.

Figure shows that growth rates have been significantly slower since 1980 than in the period from 1961–1979.

Figure 1: Annual GDP growth, year-on-year. Source: World Bank

Moreover, the wealth gain of recent decades has been very unevenly shared. While the poorest half of the world population own just 2 per cent of global wealth today, the top tenth owns three quarters of it. In the UK, the average holdings of billionaires stood at £4.8 billion in 2024, up from £3.4 billion in 2020.

‘Good’ versus ‘bad’ accumulation

Policy makers have for centuries distinguished between the deserving and undeserving poor. Yet, such a dichotomy has never been formally applied to wealth accumulators. Adam Smith wrote: The ‘disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition’ is ‘the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.’

There is no question that some members of the super-rich club, past and present, have contributed to shared economic and social success. They include Richard Arkwright, who invented the water-powered spinning machine; the Rowntree and Cadbury families, who among the first industrialists to set up an occupational pension scheme, employ a work doctor and, in some cases, build ‘model villages’ for their workers; and John Spedan Lewis who pioneered the first employee-owned partnership and profit-sharing scheme. Yet, the history of personal wealth building is also littered with unethical, corrupt and exploitative practices.

Extraction versus creation

Can ‘good’ wealth be differentiated from ‘bad’ wealth? The early economists drew an important distinction between new wealth creation that adds social value, and extraction that only serves the interests of the powerful.

‘Good’ wealth can then be defined as that which creates new value through an expansion of the real national asset and resource pool with at least part of the gains shared more widely across society, bringing decent jobs, high social value innovation or more efficient production methods.

‘Bad’ wealth is the result of appropriation, non-productive or low social value activity that adds nothing to or even depletes the stock of resources on which prosperity depends. It is associated with the transfer of existing wealth upwards, leading to a smaller pool of socially available assets, resources and often fewer jobs.

In the postwar years financial and economic elites acquiesced—if with reluctance— in the process of equalisation and prewar levels of extraction fell. By the 1970s, capital's patience was exhausted. A significant proportion of the personal wealth surge of recent decades is associated with activity that has had a malign economic, social and environmental impact. In the UK, many large companies have been turned into cash cows for executives and, increasingly, global shareholders and investors. This is also one of the explanations for the decline in private investment.

Today's global model of corporate capitalism holds a commanding nexus of control. The UK's five largest banks hold assets of over £8 trillion—more than twice the size of the UK economy. It is corporate power that has driven more monopolised markets, private equity takeovers, anti-competitive practices, the rigging of product and financial markets and the over-emphasis on financial raiding. The markets for grocery retail, energy supply, food production and housebuilding to banking, soft drinks and pharmaceuticals are controlled by a handful of ‘too big to fail’ firms.

Asset inflation, in part the product of inept state economic policy, and another source of rising wealth pools, has no intrinsic value.

A paradox of wealth

The greater the share of top wealth holdings associated with appropriation, the greater the social and economic damage at work. Yet, analysis and policy has mostly disregarded these distinctions.

Britain and other rich nations have allowed an extreme version of the paradox of wealth. As they have become richer, their capacity to meet essential needs has faltered, with resources steered instead to the low social value and often damaging demands of the rich and the power of privatised markets. Despite its dismal economic record, the UK is an asset-rich country. Yet, its defining characteristic is a mix of over-abundance and widespread scarcity of basic essentials from affordable homes and adequate diets to access to decent health care.

A moral hierarchy

The French economist, Thomas Piketty, is critical of the idea of a moral hierarchy of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ wealth, which, he says, risks being based on arbitrary judgements. This concern is valid as any exercise of this kind is bound to involve simplification. Nevertheless, such distinctions—however crude—are important for assessing the role and impact of the different routes to wealth accumulation. To promote social and economic strength and progress—it is necessary to support activity that works for these goals and discourage that which works against them. Business methods which overexploit natural resources, take the gains offshore, fail to build better infrastructure and are deliberately less than transparent would fail this test.

Any distinction between types of wealth accumulation does not provide a license for unlimited levels of ‘good’ wealth. ‘Good’ wealth may be more meritorious than ‘bad’, but there is still an overwhelming case for breaking up today's great concentrations of wealth, whatever their source. Such concentrations are still harmful. They undermine democratic accountability and the effective management of economies and misdirect resources. A concerted strategy against extraction is a central requirement for building stronger and more progressive and sustainable economies.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley