| 8 mins read

The Casey Review marks the third major review of the Metropolitan Police Service in my lifetime, starting with Scarman and MacPherson. These reports point to deep-rooted problems with how the Met operates institutionally. Scarman and MacPherson were both directed at the failings in how London's black community is served and policed by the Met. The latest review by Baroness Casey again places culture at the core of many of the problems faced by the Met, including sexism, misogyny, racism and homophobia.

How can more and better evidence help policing now?

Baroness Casey argues in her review that: ‘[p]ublic consent is broken.’ So what should the police do to gain and keep public trust and confidence?

There is painfully little evidence about what really moves the dial to improve trust and confidence, although news coverage does impact public perceptions. But it is possible to improve individuals’ trust in policing by ensuring those using the service have a good experience of it. Low- and high-stakes interactions between police and the public can be of better quality if police officers adhere to principles of procedural justice. This has been proven to create better quality interactions with the public in the US and Australia. Simply giving officers a checklist to guide how they open, conduct and close an interaction, reminding them of what ‘good’ looks like, can be effective.

Engage the public in policing through deliberation

Improving and maintaining trust also involves better engagement and communication with the public. But what does ‘better’ mean? For one, as Alastair Campbell notes, it means having a clear public engagement strategy that is not ‘what we've always done’.

Going further, there is a case to be made for a version of deliberative democracy being directly involved in police governance, for example citizens’ assemblies being trialled in Walthamstow. This ensures that a representative segment of the public's voice is heard, with recommendations flowing from these discussions directly informing decisions. It can lead to the public making sensible and actionable decisions that represent the community, help them solve their own problems and provide meaningful interaction between citizens and police.

Diversity and bias in police recruitment

If policing wants to employ different people, processes need to be debiased, the candidate market segmented, friction reduced during applications and processes made more transparent.

When advertising jobs, police forces need to understand the possible motivators of people from different demographics in applying for a role in policing (not exclusively police officers). Examples include thinking about the possible ‘hook’ for a job advert—is public service, teamwork, career certainty or otherwise advertised?

Recruitment processes also need to be ‘debiased’ as much as possible and need to be made as easy as possible for the candidate. There is substantial evidence that candidate names can be cues for biased decision making. Blind sifting, as implemented by beapplied.com for example, means organisations can find better suited candidates and interview people they may not have done otherwise.

Misconduct and complaints

Following several high-profile events, policing, the complaints process, and the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) all came under intense scrutiny in 2023. One key issue was that investigations of complaints have taken too long, a fact reflected in changes in 2020 that introduced a twelve-month limit on investigations.

Removing bureaucratic ‘sludge’ from complaints, ‘frictions that prevent you from doing what you want to’ is a good start, but it can be done differently. To make a complaint against a business, for example, the one-stop-shop resolver.co.uk can be used. Resolver is a semi-automated case management system for complaints with an advanced range of tools and data insights. Why not use a similar approach for complaints against officers?

Data analysis could also find out what are officers with lower rates of complaints doing differently. Similarly, we can find officers with higher rates of complaints compared to their peers and specialism, because that will also help policing to learn and also inform what to do (and the answer might not be ‘more training’).

But we can also prevent some candidates from becoming officers in the first place. Researchers have found that the best predictors of misconduct in policing were the number of flags during vetting, that is, before the candidate has started the job. It should be possible to triage vetting so that—above a certain number of flags—the default is ‘flipped’ to ‘do not hire’. To hire then requires additional investigation and evidence.

Culture and culture change

Good evidence on how to change police culture is thin on the ground. In my view, we have to keep in mind that behaviour change is a core part of achieving cultural change in policing. The target is to achieve a culture where racist, misogynist, homophobic and other discriminatory acts are not tolerated, ignored, or dismissed as ‘banter’. Part of achieving this is identifying and understanding barriers to behaviour change.

One barrier to behaviour change could be the mistaken belief that others in a reference group think a behaviour is acceptable (‘pluralistic ignorance’). A police force could conduct regular staff surveys to elicit views on specific behaviours, then publicise that specific behaviours are not tolerated within the organisation. But people need clear behaviours desired of them by peers and seniors too.

Why isn't research evidence already routinely used in policing?

Cynthia Lum and Jerry Ratcliffe are both former police officers and two of the world's leading policing scholars. Table 1 in the full article provides a summary of their key points. I then expand on some points to illustrate below.

First, rarely does a rigorous, evidence-based result lead to implementation as ‘business as usual’ in policing. Why? One reason is because many experimental tests in policing are treated as one-off projects. ‘How do we scale this?’ rarely seems to be front and centre.

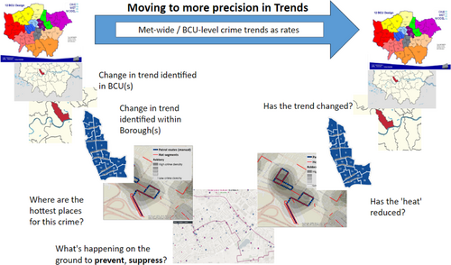

Second, operational policing focuses on responding to crime and the collection and processing of evidence relating to individual crimes. Strategic policing focuses on aggregated trends in crime and responses to them. These different approaches manifest as ‘horizontal’ thinking. Things that can bridge the layers are accountability and feedback.

Figure 1: The ‘bathtub’ from strategy to street-corner and back again

Third, those asking for analysis often lack understanding of the problems with data. For example, the smaller the time period, geographical area or just the number of observations, the more data jumps around. This means that forces might be taking credit for crime reduction when it is just a particularly wet July or, more problematically, chasing noise in data.

There exists a wide range of evidence out there that can help forces now, next month and next year. But evidence alone will not solve problems: it needs to be tested and the findings implemented.

With thanks to Eleanor Prince, Dr. Liz Ward, Dr. Paul MacFarlane, Dr. Peter Neyroud, Professors Ben Bradford and Jon Jackson for their comments.