| 6 mins read

There are two routes to becoming Prime Minister in the UK. You can either win a General Election or win a party leadership election to become head of the largest party when a Prime Minister leaves-see here. Theresa May is a ‘takeover’ leader, who takes over government by the second route rather than the first. She joins, rather surprisingly, 11 other takeover Prime Ministers in the last 100 years.

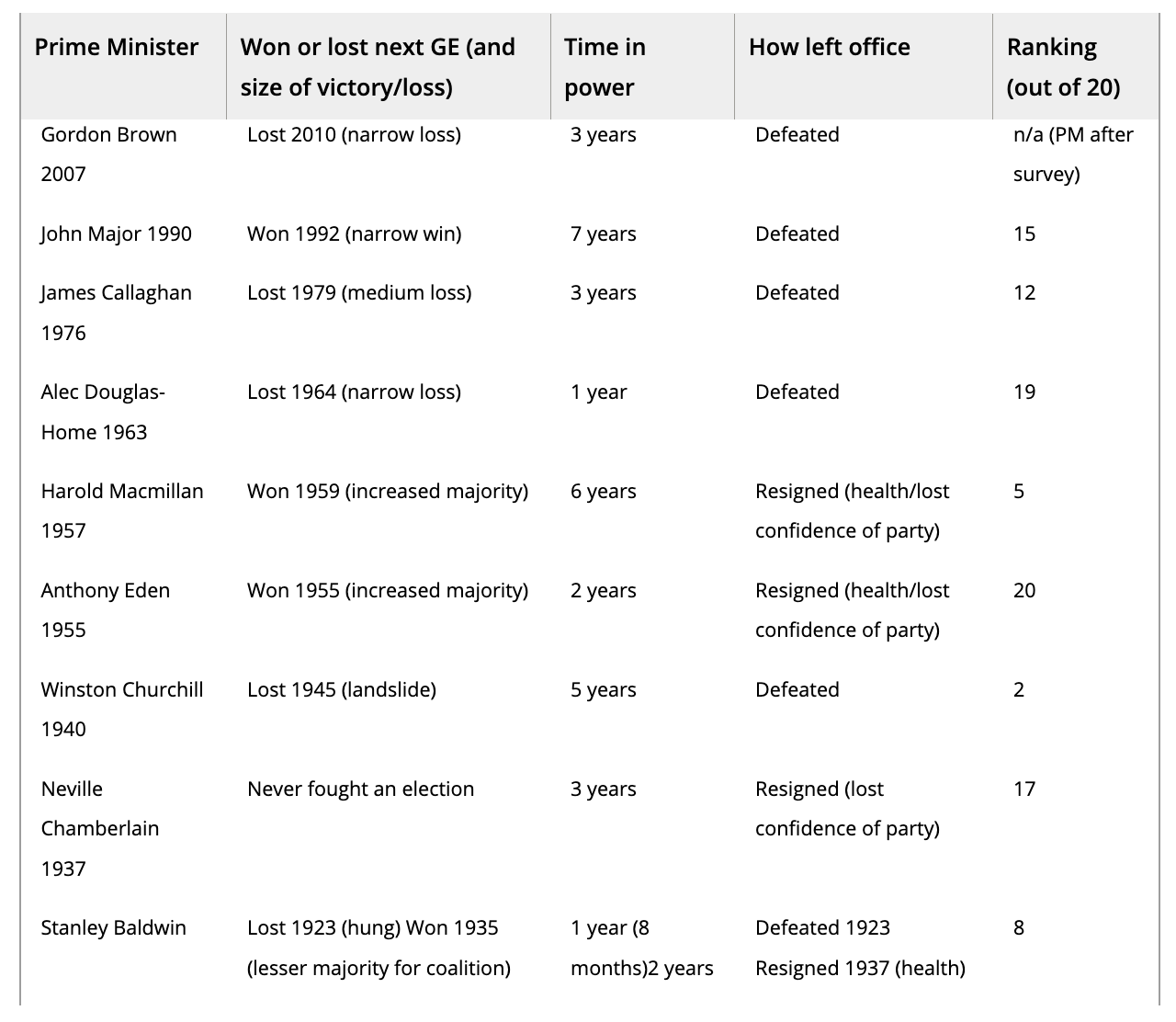

There are some downsides to being a takeover. As the table below shows, takeovers’ time in office is, on average, relatively brief. UK Prime Ministers in the last 100 years on average have lasted just over five years, one maximum Parliamentary term. Takeover tenure was considerably shorter at just over 3.6 years, compared with an average of 6.6 years for election winners. The longest takeover was John Major at seven years and the shortest premiership was Andrew Bonar Law’s seven months (due to ill health). The problem is that those Prime Ministers generally regarded as having done something or made a difference are those who have been in power 6 years or more: longevity means achievement.

Takeovers: elections, longevity and ranking 1916–2016

The experience of takeovers is also bumpy. The most recent 3 takeovers James Callaghan (1976-79), John Major (1990-1997) and Gordon Brown (2007-2010) are good examples of quite how bumpy it can be. All led deeply divided parties and their names are linked to deep crises, whether economic (The Winter of Discontent or Black Wednesday) or political (Maastricht). Only one of them, John Major, won an election and it didn’t lead to a very happy premiership.

So why are they brief and often bumpy? The lesson for May is that takeovers inherit problems, unhappy parties and short mandates.

Takeovers inherit the problems that their predecessors leave for them. These can be economic, like the recession for John Major or the crash of 2007/8 for Gordon Brown, or socio-political, such as Callaghan’s Trade Union relations. David Cameron has gifted Theresa May the extremely difficult problem of negotiating Brexit, perhaps the most complex and perilous task since Winston Churchill came to office (as a rather exceptional takeover) in May 1940 during the Second World War. The High Court judgement on Brexit looks set to make even more difficult and takes it further out of the Prime Minister’s hands.

Takeovers also often inherit unhappy parties. Callaghan, Major and Brown all battled to lead parties that were split and prone to rebellion. This meant U-turns and constant compromise, especially for Callaghan, who had a majority of 0 and Major, who had a rapidly dwindling 21 seat advantage. For Major and Brown party unhappiness led to mutiny. John Major had to call his infamous ‘put up or shut up’ leadership election in 1995 and Gordon Brown fought off 3 coups in 3 years.

May has a smaller majority than Major, with just 14 seats, a number that will magnify the influence of any unhappy MPs. This number has already dwindled from July 2016 by one due to Zac Goldsmith and another now by the resignation of Stephen Phillips. May’s backbenches now includes 11 former Ministers including ex-Chancellor George Osborne. Her party is also riven with a spectrum of opinion from hard-line and soft Leavers to Remainers. The key question is whether May’s opaque Brexit strategy, or lack of a strategy, can hold the party together or gives potential challengers like Boris Johnson ammunition and time to prepare.

Takeovers inherit mandates and are a little reluctant to call elections and often try, as Churchill put it, to ‘stay in the pub until closing time’. Like Gordon Brown before her, May faces the charge of not only being unelected by the populace but also of being ‘crowned’ unopposed by the party. If May were to call an early election it would make her the first in more than half a century not to hang on-if she won a larger majority she would be the first takeover to do so since MacMillan in 1959 . May faces a slight harder task in ‘calling’ an election than her predecessors, as technically an election would need to meet the terms of the Fixed Term Parliament Act 2011, requiring a vote of no confidence or a supermajority. This can, however, be gotten round by pushing a ‘reset’ law through Parliament, though it may not be straightforward.

Takeovers face greater obstacles and fewer advantages than elected Prime Ministers: their time in office is often nasty, brutish and short. On average they have less time in power, less chance of winning elections and are generally rated as worse performing (though Major’s stock in rising post Brexit). May will need a large amount of skill, luck and support (and probably the safety of a general election victory) if she is to avoid the short unhappy fate of the takeover Prime Minister.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley