| 7 mins read

The coronation is a constitutional event where the history, religious significance and constitutional role of the monarchy most visibly intersect. Its rules are largely uncodified. Many of them are binding and understood to be constitutional in nature, called ‘constitutional convention’.

Convention, however, is a term that is often used too loosely. In fact, there are two other types of unwritten rules that resemble conventions, but lack their binding authority: practice and customs. The coronation involves these other rules as well.

Differentiating convention from practice and custom

Conventions are the unwritten political rules of the constitution. They distribute power and authority between and among constitutional actors and institutions, often in ways that modify formal law. Conventions can ensure that constitutional principles are given effect in the operations of the government, the courts and Parliament. They can also preserve and protect longstanding political settlements that are deemed vital to the functioning of the constitution. Conventions are firm, but inherently flexible.

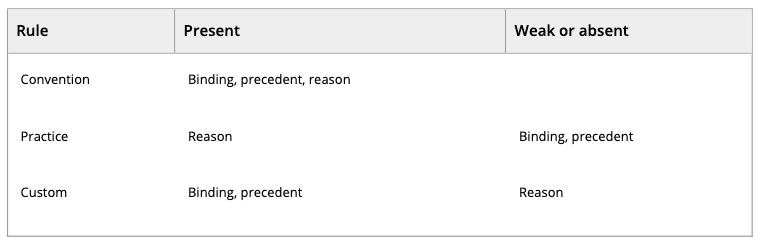

As set out by Ivor Jennings, for a rule to count as a convention, it has to meet a three-part test. First, constitutional actors must believe that they are bound by the rule. Second, there must be precedents underpinning the rules. Third, there must be a reason for the rule. Only a small number of conventions meet the Jennings test. This framework suggests that greater care should be taken when describing various kinds of unwritten rules as convention.

When it comes to the British constitutional monarchy, the most important convention is the rule that the sovereign almost always acts on the advice of a prime minister whose government holds the confidence of the House of Commons. As with most conventions, this rule took centuries to solidify and remains flexible.

Practices are guided by a reason and may have some precedents, though they are not considered binding. In many cases, practices are auditioning to become conventions. For instance, the sovereign first began acting on the advice of ministers as a practical matter.

An example of contemporary practice that has not yet graduated to convention is the rule that the government should consult the Commons before undertaking a major military deployment overseas. The government recognises that there is a rule that the Commons should be consulted, but its boundaries are fuzzy and there is scant evidence that prime ministers believe they are bound by it. Therefore, this practice is still auditioning to become a convention.

Whilst practices do not have the binding power of conventions, customs are considered binding, but on account of tradition, rather than a constitutionally salient reason. They are largely cultural phenomena, rather than constitutional ones. The wearing of wigs by judges is an example. We know we are dealing with a custom when it could be abandoned or changed without much constitutional impact.

An illustrative case of a custom that was once convention is the rule that the Crown does not enter the Commons. This rule has centuries of precedent and it is still followed, but its rationale is no longer compelling. The rule dates to the time when Charles I entered the Commons with his soldiers to arrest five MPs in 1642. There is no compelling reason for this rule any longer; it is simply customary.

Returning to Jennings's test, the three rules can be differentiated as follows:

Table 1. Convention, practices and customs

Convention, practice and custom at the coronation

The accession of a new monarch offers an opportunity to analyse the coronation ceremony, and to see new practices that may become conventions.

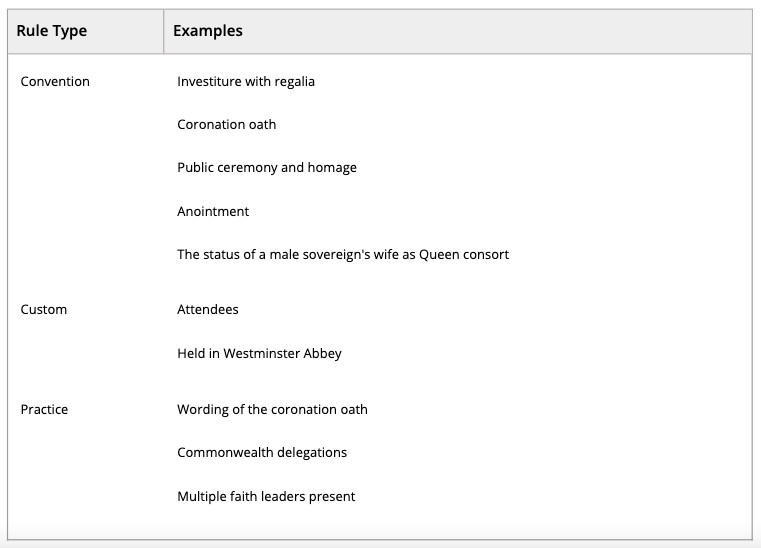

Although the ceremony is more than 1,000 years old, the coronation has consistently adapted. Most of the binding rules of the coronation are tied to the order of service devised by Dunstan more than 1,000 years ago. Central elements of the ceremony—including a public recognition of the monarch's legitimacy, a coronation oath, an anointment with holy oil, an investiture with royal regalia and paying of homage—remain bound by convention.

The public nature of the coronation ceremony is a conventional rule, insofar as it is meant to ensure that there is no dispute concerning the legitimacy of the new reign. Thanks to the decision to televise Queen Elizabeth II's coronation in 1953, King Charles III's ceremony benefitted from a clear template. A comparison of their two coronations offers further insights into unwritten rules at play. King Charles III's coronation had a strong emphasis on community leaders rather than the titled aristocracy, reflecting that the contemporary Crown requires the support of the wider population.

Since 1066, the location of English (and later British) coronations has been Westminster Abbey. Yet it would be difficult to articulate a clear constitutional rationale for this, indicating that the Jennings's criteria are not met.

The status of a male monarch's spouse as Queen consort is also a longstanding rule that dates from the coronation of Edgar the Peaceable in 973. The rules surrounding Queen consorts are arguably constitutional conventions. Several acts of parliament have governed the marriage of future monarchs. Critically, the Church of England now accepts the remarriage of divorcees. The crowning and anointing of Queen Camilla in 2023 demonstrates that the rules surrounding Queen consorts can evolve as convention, serving as public affirmation of the legitimacy of the sovereign's marriage. This convention may be slowly tipping toward becoming a custom, but it would still appear to meet the Jennings test.

In addition to conventions and customs, each successive coronation involves new practices that reflect contemporary considerations. For example, King Charles III's coronation saw the Commonwealth delegations being granted greater visibility during the ceremony and there were faith leaders from various religious traditions.

Table 2. Contemporary conventions, customs and practices of King Charles III's coronation

Conclusion

If the monarchy endures in the coming decades, the accession of William V will likely result in further coronation customs falling away. For example, the estrangement between William and his younger brother Prince Harry may result in all the royal dukes and senior figures in the line of succession no longer being present for coronation ceremonies. The number of people present in Westminster Abbey may contract further the conventions of the coronation, however, are expected to endure as long as the coronation remains a veritable constitutional event.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley