| 8 mins read

Allotments are an unglamorous feature of Britain's urban life. The last official government study was written in 1969 and largely ignored.

Allotment plot provision in the UK is protected by various acts of Parliament dating back to 1908. It grew after the two World Wars, providing a source of both food and outdoor activity for urban working class communities. Numbers peaked in 1950. Postwar, allotment usage declined with approximately 1.5 million plots falling to around 300,000 in the late 1990s.

However, recent years have seen a revival of interest. Over 150,000 people are on allotment waiting lists across the country, up 81 per cent from twelve years ago. The vast majority of allotment sites are located on public land owned by local councils. Voluntary allotment committees oversee the smooth running of the sites.

An increasing awareness of the realities of climate change, along with the importance of fresh food, links to nature and healthy living are resulting in a burgeoning interest linked to a wider food policy movement evolving across the UK.

The Birmingham allotment picture

Birmingham has 255 hectares of allotment land that currently provide around 7,300 plots. The plots are in four distinct size categories—mini, half, standard and large. A standard plot currently costs £110 annually. For over 65s, rent is discounted by 50 per cent. The geographical distribution of allotments is fairly evenly shared It appears that well in excess of 12,000 people are regularly engaged in allotment activity.

Scope and methodology

Our study collected information directly from both allotment users and committee secretaries in Birmingham. In total, 876 valid forms were completed, which represented 14 per cent of current plot-holders and represents by far the largest study of allotment tenancies of recent decades. As well as these two surveys a range of calls and discussions were held with tenants.

The changing face of plot-holders

The standard image of allotment holders has been of a stable, elderly male population. However, our returns show that marginally more tenancies are now held by women. Secondly, there is a growing spread of ages. While 50 per cent of plot-holders are 65 years or older, a fifth are 30–49 years old, with almost 30 per cent aged between 50–64.

The most common category is professional employment (44 per cent) with manual work recorded at 13 per cent. 15 per cent of plot-holders come from an ethnic minority background, although here and with manual workers there is possible under-representation due to lower response rates from particular parts of the city in the sample.

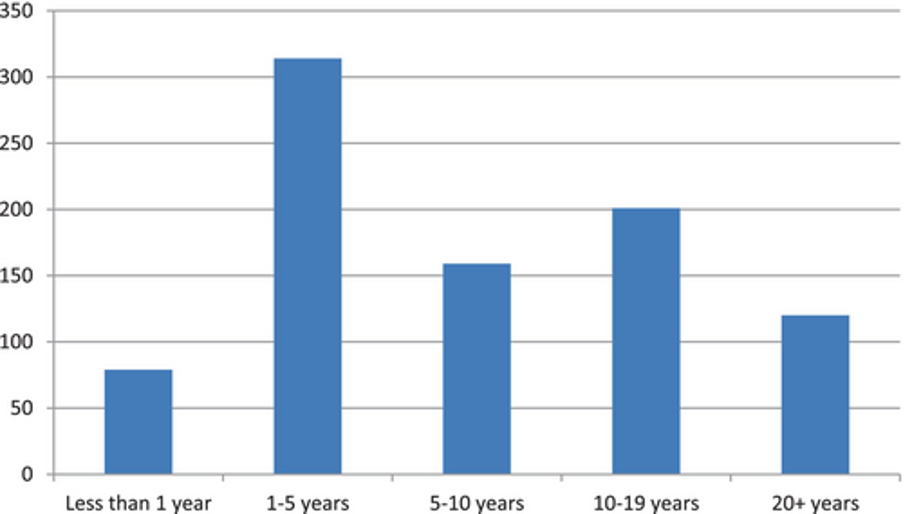

There is also a steady flow of newcomers. 36 per cent have had a plot for between one and five years, while 9 per cent have acquired a plot within the past year.

Figure 1: How long have you been a plot-holder?

There is also a clear shift towards more flexible plot sizes.

The core data on food production

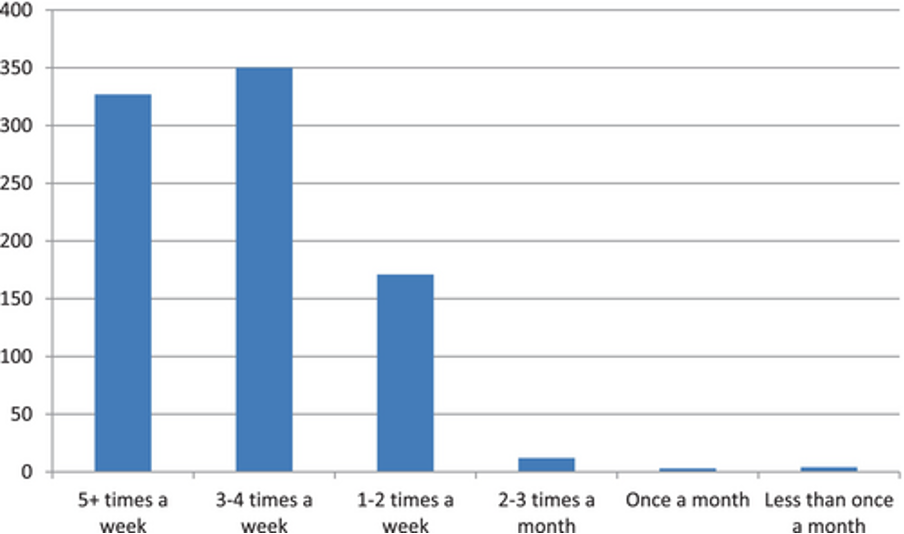

Most plot-holders see an allotment tenancy as a substantial leisure activity. (see Figure 2.)During the main growing months—spring, summer and early autumn—three-quarters of plot-holders go to their plot at least three to four times a week.

Figure 2: How often do you go to the plot in summer?

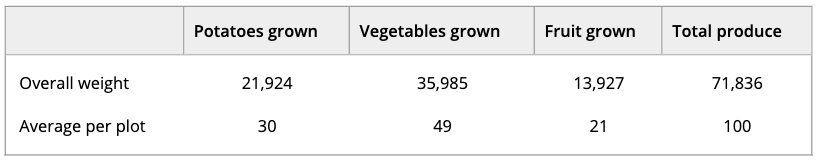

On the questions concerning estimated weight of produce harvested, figures were provided by plot-holders but these should be considered as rough estimates.

Table 1: Estimated weight of produce harvested in 2023 (kg)

The most common crop was potatoes, which 88 per cent of plot-holders grow. Of those who estimated the weight of their crop, the average grown was 30 kg per plot. As a point of reference, annually, people typically buy 35.1 kg of potatoes either fresh or prepared.

The most popular vegetables are onions and shallots, brassicas, tomatoes and courgettes with more than three-quarters of plot-holders cultivating these crops. Many plot-holders are looking for a breadth and variety rather than mass volume.

The growing ethnic mix of plot-holders has encouraged the cultivation of crops such as callaloo and sweetcorn. Of those who estimated the weight of their crop, the average weight of vegetables harvested in 2023 was 49 kg.

Rather less fruit than vegetables is grown. The most popular fruits are strawberries, rhubarb and raspberries. The average plot produced 21 kg of fruit in 2023.

Our sample indicates that on average 100 kg of fresh produce was harvested on each plot in the city. Approximately 630,000 kg or 630 tonnes of food are being grown on allotments each year across the city.

The physical and mental benefits of allotment life

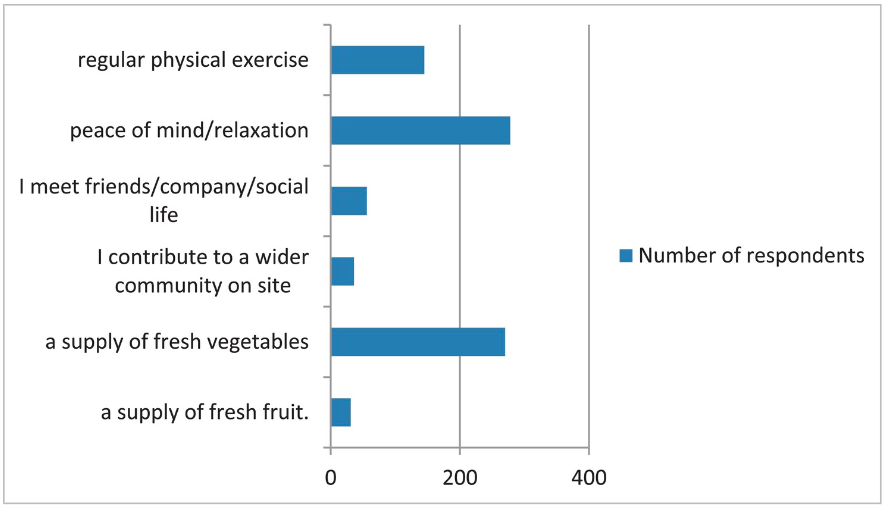

In our survey, scores of over 90 per cent were recorded for those stating as a benefit regular physical exercise; peace of mind and relaxation, as well as a supply of fresh vegetables. In the survey’s most significant finding, (see Figure 3) when asked to identify the most important single benefit of being an allotment tenant, peace of mind and relaxation emerged at the top of the poll. It was the main priority for 32% followed by 31% for supply of fresh vegetables and 17% for regular physical exercise.

Figure 3: Open in figure viewerPowerPoint Which of these benefits is most important to you?

Zahora's story is illustrative. A 40-year-old Asian housewife, she shares a full plot. She said: ‘I used to suffer from anxiety. The GP gave me pills. But I just find it so relaxing down here, away from it all, that I don't take them now.’

Our findings have significant implications for the NHS and community care services. Allotments should be part of the narrative to shift the policy balance within the NHS away from hospitals and acute care to primary and community care. Local councils should give a higher profile to allotments in their environmental and ‘green spaces’ policies; and in the house-building and planning system.

Allotments: the community dimension

Allotments are a public asset and need regular care and repair.

Austerity policies have had a knock-on effect on allotment support as in every other service area. There is now only 0.6 of an officer within the local authority responsible for managing the 7,000 plus plots compared with five officers up to 2015. The management of allotments depends on the energy and enthusiasm of the volunteers who run the sites. The strain is beginning to tell; more solid institutional support is needed.

Should there be a shift in allotment culture? A more outward-looking profile for allotments not only helps sites to attract funds, but also to make sites more of a community hub.

Conclusions

Allotments are essentially a low-cost public investment, which encompass a whole range of interventions including local food sourcing, social prescribing, empowering local communities and protecting green spaces. However, policy strategists tend to follow politicians in thinking in departmental silos.

The allotment movement has substantial potential but it remains a neglected backwater. There is a real opportunity for the new Labour government, in close partnership with local councils and health boards, to grasp the pivotal potential of these public assets.