| 6 mins read

High Speed 2—the planned new railway from London to the north of England—is one of the largest and most controversial public sector investment projects Britain has attempted in decades. Much has been written about the huge cost overruns and why this led to the eventual cancellation of the line beyond its first phase now under construction. Our aim is to offer some commentary on the wider political context and of how the project first flourished and then foundered.

Is Britain exceptional when it comes to high speed rail?

Building HSR is often as much about increasing wider capacity as it is about reducing journey times. In some cases, the classic railway network is of such a low standard that new build infrastructure is imperative. It offers a realistic low-carbon alternative to flying and can be a nation building enterprise.

The British classic rail network is both extremely busy and under-invested by European standards. Journey times between even the largest regional cities can be extremely long by international standards.

Critics point to high land prices in the UK, but the land take for a new HSR line is usually lower than that of a new motorway. Many continental European routes have required complex and ambitious engineering to deal with challenging topography. There is nothing exceptional about Great Britain in geographical, economic or engineering terms.

The infrastructure that Harrods would sell you

Where Britain is exceptional, is in just how much it costs to build any sort of transport infrastructure. Civil engineering works cost sixty percent more than in Germany. Granted, there are higher land costs, but there are also too many organisations and contractual boundaries, a slow planning pipeline, and a ‘stop-go’ culture that fails to give the supply chain certainty of demand.

Second is a predilection to ‘gold plate’ everything in the rare event that something new does manage to get built.7

The benefit:cost monster

How we do transport economic appraisal is a benefit:cost ratio (BCR) that provides a single number to describe hugely complex impacts. The ‘economic case’ for HS2 ultimately hinged on the time travellers would save. The ultra-fast project that emerged was the only option that could generate a sufficiently juicy number to satisfy the benefit:cost monster. It was an almost dead straight 400 km/h railway requiring enormous lengths of tunnelling. We could have a fork more closely following the M1/M6 and explained its benefits in more rounded economic, environmental and social terms, as the beginning of a national network.

When costs began to rise, there was no overarching narrative, nor convincing answer to the simple but devastating question of ‘why do I need to get to Birmingham in 49 minutes?’.

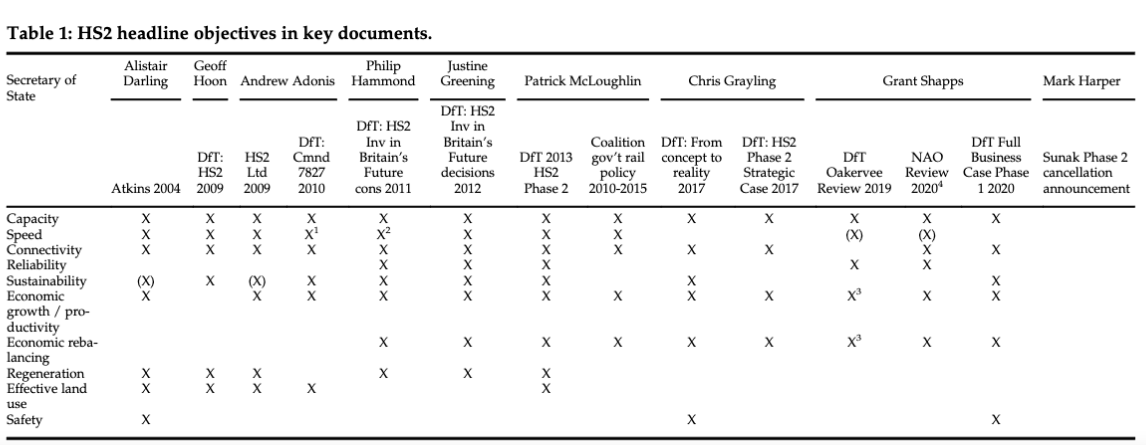

Table 1. HS2 headline objectives in key documents.

Notes for table:

- A bracket indicates the benefit is not played up especially strongly. In some of the documents there are additional benefits but not as part of the headline case. Broadly the same factors appear over the lifetime of the project, although sustainability fades and then makes a comeback, and capacity and economic growth start to become privileged over speed to the point where some later Department for Transport (DfT) documents don't even headline it as an objective. A fuller list of objectives from HSUK is available here.

Additionally:

- 1 = London to Birmingham 30 mins.

- 2 = London to Birmingham now 49 mins…

- 3 = But only if ‘properly integrated with other transport strategies… and also with national, regional and local growth strategies’.

- 4 = NAO's summary of the government's objectives for HS2.

(Absence of) the rizz

The second under-appreciated part of the story is the importance of key charismatic individuals, who in transport policy are rare beasts because the timescales involved.

HS2 was adopted as government policy following sustained work by one such charismatic advocate, Andrew Adonis. George Osborne was also committed to transport, as was Boris Johnson, despite vocal Conservative opposition to escalating costs. The casualty at this point was the so-called eastern leg from Birmingham to Leeds.

But without sufficient rizz evident in Downing Street, political enthusiasm for the project evaporated. Animated sceptics such as Andrew Gilligan seized the opportunity to curtail the project, mobilising the headline BCR figure.

Driving a train through good governance

It is no exaggeration to say that Rishi Sunak's decision to cancel HS2 upended fifteen years of carefully crafted cross-party consensus in a way that no other major area of government policy has seen in the modern era—and for no apparent political gain. Institutions such as the National Infrastructure Commission and Infrastructure Projects Authority were not consulted. HS2 was about as close to a coherent spatial planning framework as had been in place for decades. The DfT's credibility with Number Ten and the Treasury fell. Key international engineering groups wasted time and money building their staff base and supply chain in the UK. Expertise will now inevitably be lost. The market will never again approach a mega project in any key sector with a pre-HS2 mindset.

What then is the plan for England's economic geography?

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley