| 6 mins read

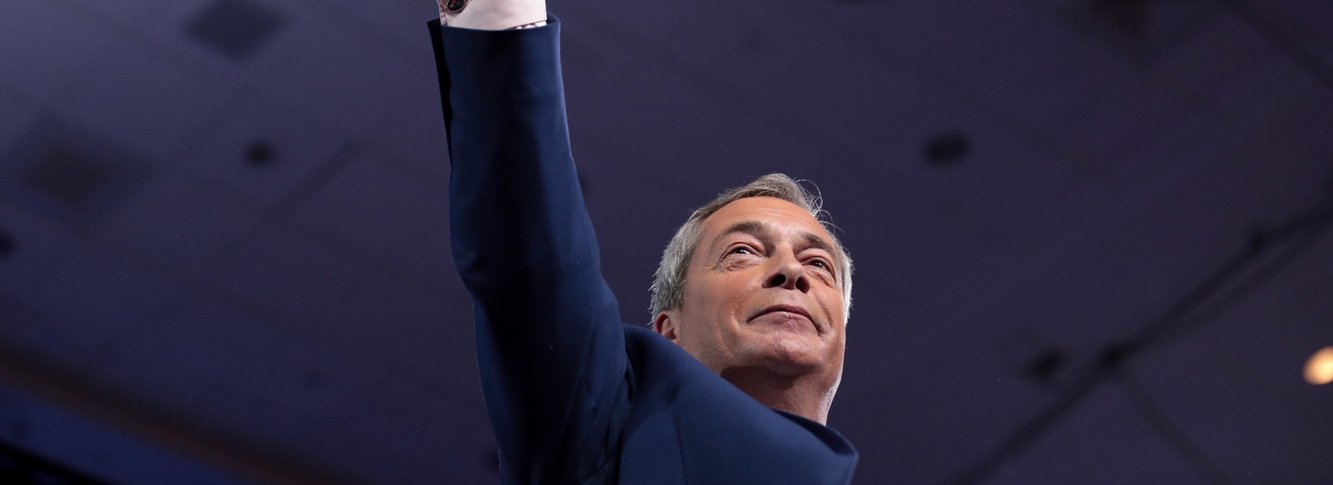

When Nigel Farage became leader of UKIP in September 2006, few in mainstream British politics considered EU withdrawal to be politically ‘thinkable’. Yet, within a decade, Brexit happened. Farage was one of many ‘bad boys of Brexit’ who campaigned for a referendum; a decisive player that secured the outcome.

Whatever his fiercest critics might think, Farage is sufficiently significant to deserve a serious, full-length biography, and Michael Crick is its ideal author; an unwelcome intruder for those who want to evade critical scrutiny while exercising political influence. Packed with controversial personal and political episodes, few readers will change their minds about Farage, yet even the most dedicated ‘Leavers’ may find their idol revealed as more flawed than they had originally supposed.

A rule breaker

Having denounced work in the EU as a ticket to board a ‘gravy train’, Farage embarked on a long career as a Member of the European Parliament (1999-2020). While he slurped happily on the ‘gravy’, Farage restricted his parliamentary contributions to sporadic speeches often attacking fellow colleagues, which europhobic press back in Britain would then readily equate with “standing up for British interests”. Aside from this public image, Crick illuminates the more serious charges levelled against Farage such as breaching rules related to financial support for parties within the EU.

Crick’s investigation of Farage’s schooldays reflects this ‘pick and choose’ attitude to formal rules and a reputation as a rule-breaker from a young age. Although Farage went on to make plenty of money through his association with London’s Metal Exchange in the City of London, politics was a promising alternative avenue to the fame he sought more than fortune. He had joined the Conservative Party just before Thatcher’s first election victory in 1979, and later signed up to the eurosceptic Anti-Federalist League in the 1990s as the UK hurdled toward EU alignment under the 1991 Maastricht Treaty.

In terms of the public profile he always craved, Farage owes everything to Maastricht and the creation of the EU. Crick’s account demonstrates that Farage’s euroscepticism was another product of his childhood, so deeply ingrained that no factual evidence could ever shift it. Brought up in Kent, close to legendary scenes of British prowess like the Biggin Hill airfield, the young Farage readily absorbed the commonplace myths which continue to persuade people that the plucky English underdog took on and beat the whole world single-handedly between 1939 and 1945.

As Crick notes, another unwitting servant of Farage’s ambitions was New Labour, whose adoption of proportional representation (PR) for European parliamentary elections produced impressive results for UKIP which made it look like an existential electoral threat to Labour and (particularly to) the Conservatives. By promising a referendum in 2013, David Cameron lent credibility to UKIP rather than stamping it out as he had hoped. Yet outside of UKIP Crick suggests that Farage’s real ambition was to host a television programme. Through his brief spell as leader of the ‘Brexit Party’, which helped hand the Conservatives a substantial victory in the 2019 general election, Farage arrived at his favoured destination courtesy of GB News.

A great political communicator?

Summing up his subject, Michael Crick writes that ‘egotism, arrogance, dishonesty, hypocrisy, all are attributes which Nigel Farage has in abundance’. This collides with what his supporters saw him as: a crusader against corruption in the EU and a ‘breath of fresh air’ to other politicians in the UK and EU. Instead, Crick’s character assessment implies that, at best, Farage was offering a more charismatic brand of the same kind of corruption which brought Britain’s political class into contempt thanks to the 2009 expenses scandal.

According to Crick, Farage ‘will go down as one of the great political communicators of our age, a man with a rare instinctive feel for public opinion’. Yet, after reading this meticulously researched biography, it is difficult to accept that the epithet ‘great’ could fairly be attached to any aspect of the career and personality of Nigel Farage. In a liberal democracy a ‘great’ communicator, surely, is someone who can make complex political debates comprehensible to individuals so that they cast their votes with a sense of responsibility. Farage, like Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, instead had the unhappy knack of persuading too many citizens that they can vote frivolously without incurring any subsequent penalty.

An alternative assessment of Farage, on Crick’s evidence, is that he was effective as the plain-speaking advocate of the disenfranchised millions; a prominent figure on the winning side of the referendum debate. But Farage did not create the volatile electorate of 2016, which was frantic for easy scapegoats and more interested in ‘reality’ television programmes than in the trivial details of politics.

It is a safe assumption that nobody in Britain is better informed about the forces which affect the country’s prospects as a result of anything said or written by Nigel Farage. As for UKIP, after the 2016 referendum, the party label seemed equally redundant to British voters, since its message of combative, unreflective and self-defeating English nationalism had been entrusted to a much longer-established and even more successful entity—the ‘Conservative Party’.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley