| 7 mins read

Traditional democracy is creaking. The process of politics itself needs to change – the stakes could not be higher. Policy making, and the practice of ‘doing’ politics, needs to be made more accessible to the public. For those on low incomes who have been under‐represented in particular, public attitudes led policy making could be a means to counter populist movements and restore faith in our democratic life.

Political inequality in our democracy

The political theorist Robert Dahl described the democratic ideal as, ‘In making collective decisions, the … interests of each person should be given equal consideration.’ Many members of the electorate would suggest we are a long way from this ideal.

Those on low incomes in particular feel politically less well represented by our democracy, and are less likely than those on higher incomes to be politically active. NatCen found that people living on a low income say they feel that the ‘decks are stacked against them’.

Overall, ‘people on low incomes feel less in control of their lives and have less faith in politicians to act in the national interest’. The narrowness of the backgrounds of professional politicians, as society has become more diverse, compounds the problem.

Interest in politics has increased since the EU referendum, but the public’s sense of political satisfaction and efficacy have declined. If anything, the chasm between the governed and those governing seems to have widened since the referendum.

This is a particular challenge for democracy that needs to be addressed.

Public legitimacy as a goal of policy making

If politics and political representation appear to have become increasingly disconnected from the public, so too has the process of policy making.

In the current British political system, public engagement is primarily sought through the ballot box. Modern policy making has become the convoluted business of a professional elite. Politicians often mediate policies through a wider network that stretches beyond the civil service, to organised lobby groups, businesses, public affairs agencies, universities and think tanks. This is a legitimate part of democracy, but it can mean that the views of sections of the electorate are often overlooked, particularly when those perspectives contrast with the views of experts.

At the same time, a too‐narrow conceptualisation of the voices that matter can draw politicians to policies that play well to particular constituencies. In so doing, the wider interests of citizens who have relatively less power can seem more remote to policy makers.

Public opinion and legitimacy

Public opinion is clearly central to political decision making. But the practice is currently fairly blunt and one-dimensional. It can result in policies that have been under‐tested in design or opinion.

Traditional use of public opinion has not necessarily been experienced by the electorate as a democratically enriching process, and there is nothing to suggest that it is increasing voter engagement over time.

In the longer term, lack of public legitimacy can make policies easier for successive governments to dismantle. But a new kind of policy making rooted in public attitudes could guide politicians to a more meaningful long‐term programme of action.

Public attitudes led policy making model

Public policy making should be rooted in understanding the needs, preferences and attitudes of the public if it is to secure greater democratic consent. New forms of democratic innovations could be incorporated to strengthen traditional engagement.

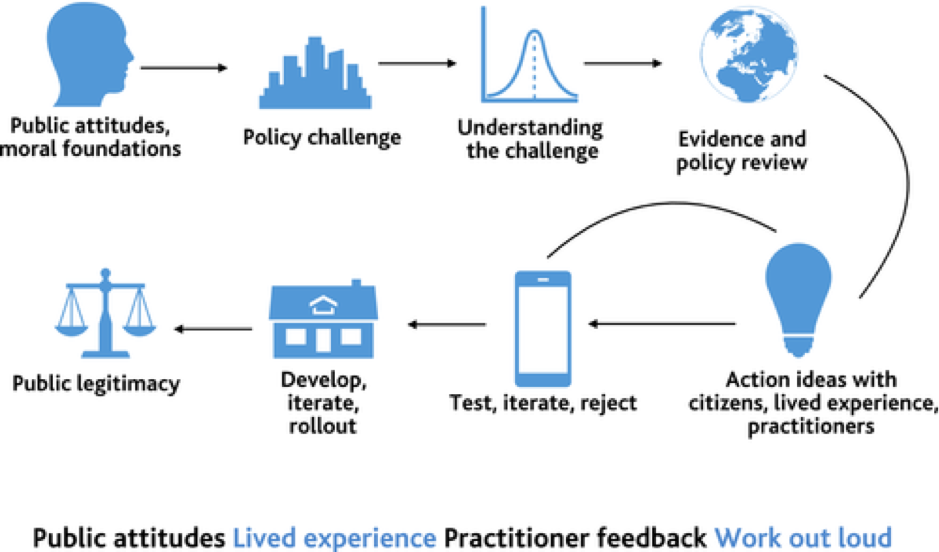

In The New Working Class: How to Win Hearts, Minds and Votes, I propose a new ‘public attitudes led policy making model’ (see Figure 1) as a means by which to introduce public attitudes into the founding stages of policy development.

Public opinion should not be seen as an obstacle or a fixed component. Instead, policy making could seek public legitimacy for policy decisions. It could use evidence and user‐testing approaches for much more effective policy that commands public confidence.

Figure 1: Public attitudes‐led policy‐making model

The model draws on the large body of public attitudes’ insight which is available and covers a sweep of issues relevant to policy makers. On any given topic, it is vital that there is access to high quality evidence to inform any proposition to test. Attitudes are available by demographic category. If an evidenced view that treats the public as equal citizens is taken, it could go some way to addressing the distortions that a fixation on voters in marginal seats or swing voters has created.

Innovative democratic methods such as citizens juries, hackathons and participatory budgeting could be used as part of this model.

User‐centred design in politics

The basic principle of putting the member of the public at the centre of policy making is an application of user‐centred design which has taken off in the private sector, and is increasingly being applied in parts of the public sector – seen in the work of the behaviour insights team.

There are many possibilities. Take public attitudes to the government’s role in the economy, for example. There is strong public support for an active government to support industry. Current policy could be enhanced if it ran through the stages of actioning ideas with industry and citizens, testing and learning, improving approaches as they develop in real time. Democratic innovations need to address the ‘social participation’ gap to ensure that people who might otherwise be excluded are equal participants.

The prize could be a long‐term settlement between a new active state which reflects citizen expectation of support for industry, but one which is responsive to the way that markets and individuals behave in reality. In this scenario, public confidence in policy direction is secured through its basis in attitudes.

All this has to be done within a framework of positive values; otherwise the risk is that weak leadership bends to the whim of public opinion.

This public attitudes led policy making model can provide an alternative to emerging populist movements, by building in a clearer role for public engagement in the shaping of policy and reinvigorating democracy for an era of participation.