| 7 mins read

The Co-operative Party was founded in 1917. It would initially concern itself largely with the material concerns of the co-operative trading movement; however, over time, this would give way to a broader focus on the ideas which underpinned co-operation.

Further, it concerned itself with the ‘consumer interest’, such as advocating for essential goods to be made affordable and of suitable quality (as opposed to the ‘producer’ interest, represented in a political sense by the trade unions and the Labour Party). It also emphasised non-statist ideas and alternative forms of public ownership, contrary to the dominant Labourite and statist approach of the time; it was consequently ‘squeezed out’.

The Co-operative Party and New Labour

The 1980s were not kind to the Co-operative Party; its MPs disproportionately left to join the fledgling Social Democratic Party. But Peter Hunt—appointed as Co-operative Party general secretary in 1998—was more closely attuned to New Labour. He created a Co-operative Party-owned think tank named Mutuo which created policy ‘heft’ and soft influence.

For example, the government sought to introduce foundation trusts to the NHS in 2002. The Co-operative Party campaigned directly to an audience of sceptical MPs and played a key role in designing the membership elements of the trust through relationships between the Department of Health, Mutuo and others. The legislation passed, reflecting the core of the Co-operative Party strategy in the New Labour context: align the Co-op's goals with those of the party leadership and play a constructive role in policy development through Mutuo.

Generally, the Co-operative Party was not a notable feature of the New Labour period. The lessons for the Co-operative Party appear to be not to place all eggs in a single basket and to avoid relying upon their very presence in Parliament as sufficient to gain policy influence. More positive lessons are to be adaptable, focus on the formation of durable relationships with influential figures, situate the party within influential policy networks, and to act when opportunities arise to shape debates and pursue goals.

In opposition, the party grew. Ultimately, the party is larger and better off today than ever before. Through not being seen as any kind of internal threat to the Labour Party, it has been allowed to operate as a support act.

The Co-operative Party recruited ‘up and comers’ in the Labour Party, including Jonathan Ashworth, Lucy Powell, and Stephen Twigg. The main Co-operative imprint on Labour policy was successfully persuading Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell to commit to a doubling of the size of the co-operative sector as a means of creating a more socially conscious private sector.8 This pledge has been retained by Keir Starmer.

MPs: the co-operative difference

All Co-operative Party MPs are Labour MPs, but most Labour MPs are not Co-operative MPs. Co-operative MPs tend to engage more with areas such as financial mutuals or building societies, co-operative and mutual enterprise, fair trade and membership organisations. For some MPs, the Co-operative label appears to be largely ornamental, while for others it is a key part of their political identity. That said, in the most significant policy changes the party's MPs have tended to be central: Gareth Thomas's Industrial and Provident Society Act (2002) and the co-operative schools agenda supported by Ed Balls.

The policy agenda of the contemporary Co-operative Party

The Co-operative Party went into the 2024 general election with four key ‘asks’ of the new Labour government.

- Double the number of co-operatives (rather than more generic social enterprises or member-owned businesses);

- promote and enhance local ownership, such as introducing a community ‘right to buy’;

- grow the number of energy co-operatives, congruent with Labour's plans to introduce a state-owned energy company;

- tackle retail crime such as violence against shopkeepers and shoplifting.

However, their goals do not end there. Opportunities will likely present themselves, likely to flow from Co-operative MPs in ministerial office. The most promising being Jonathan Reynolds who Starmer appointed Secretary of State for Business and Trade.

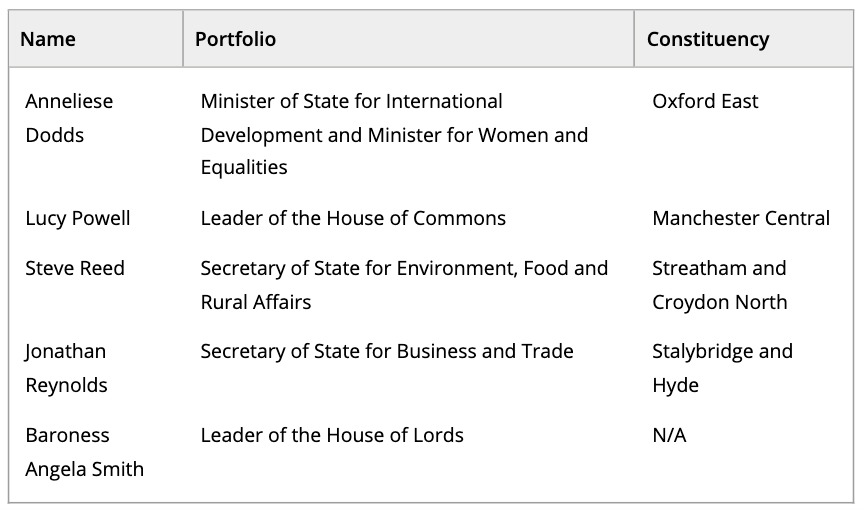

Table 2. 2024 Co-operative Cabinet members, July 2024

Reynolds is joined in Cabinet by two legislative ‘business managers’: the Leader of the House of Commons Lucy Powell and her Lords’ counterpart Angela Smith. Steve Reed—Secretary of State for DEFRA also carries the Co-operative badge and has responsibility for water and sewage (amongst other responsibilities). Finally, attending Cabinet (though not a full member) is Anneliese Dodds as development minister (and concurrently women and equalities minister). One potentially promising straw in the wind relates to the November 2024 announcement by Chancellor Rachel Reeves of the creation of the new Mutuals and Co-operative Business Council. What role it will play in economic policy making remains to be seen.

A multilevel Co-operative Party

The devolved governments in Scotland and Wales should not be forgotten. Co-operation and mutualism were not huge features of the Labour-led executives prior to the SNP's rise to power in 2007. Despite this, several notable policies developed under SNP leadership align with Co-operative Party priorities, such as a focus on social enterprise, community empowerment and support for credit unions. Influence is, however, difficult to demonstrate. In Wales, the party has a stronger tale to tell, with three first ministers being Labour/Co-op members of the Senedd.

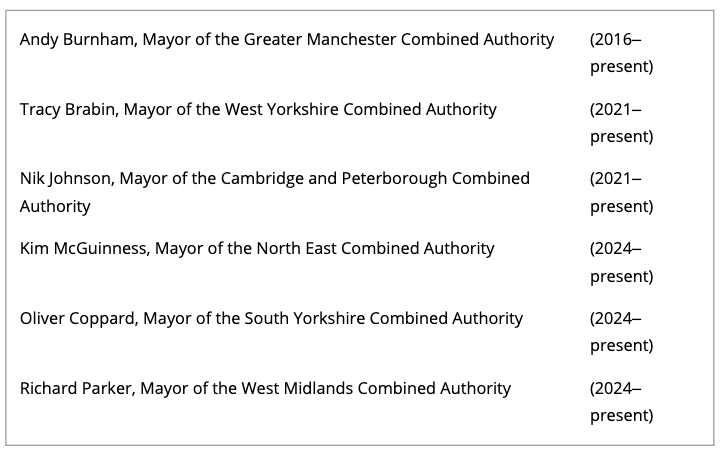

The Co-operative Party has also strongly improved its position in local government, with 1,600 local councillors—around a fifth of the total number of Labour councillors nationwide. Councils are severely limited in what they can do, but overt support for co-operatives is evident in councils—such as Preston in North West England—which have adopted ‘community wealth building’. Furthermore, following the 2024 local elections, six combined authority mayors are Labour and Co-operative, reflecting an unheralded success story (see Table 3).

Weighted against this is a strained fiscal context, a centralised party and governmental apparatus, a misfiring 10 Downing Street, government unpopularity, and a crowded policy agenda. Ambitious agendas often fail owing to an inability to ‘join up’ or co-ordinate across different departments and territorial levels of government. Starmer may lead Britain's most ‘Co-operative’ government yet, but only time will tell whether opportunity translates to substantive policy gains.

Table 3. Labour and Co-operative metro mayors

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley