| 16 mins read

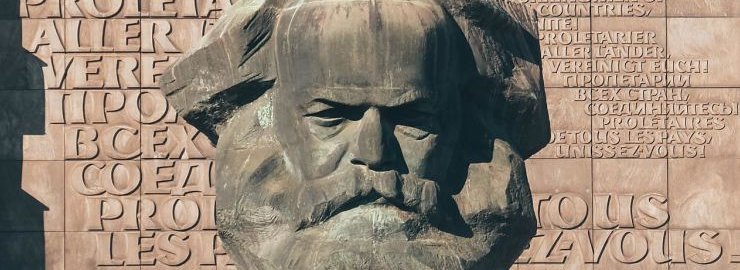

Although Marxism as an organised force is a shadow of its Cold War heyday, we seem to live in a time when calling someone a Marxist can still inspire a strange political frisson. Whether it’s the England football team protesting racial injustice or the Shadow Chancellor forswearing Capital, the charge of being a ‘Marxist’ has made a comeback as a political insult. And once again it is being brandished by partisans who have a shaky grasp of Marxist ideas. Of course, the legacy of Marxism runs much deeper than this political point-scoring suggests. In one sense Marxism never went away, for as a method of understanding modern economic history it still retains considerable purchase, even though few of the commentators who help themselves to a selection of Marx’s concepts would identify as a devotee of the man himself.

Andrew Gamble’s Marxism

The intellectual trajectory of Andrew Gamble is a fascinating illustration of the fortunes of Marxist thought in Britain. He has been a subtle exponent of a Marx-influenced political economy within the citadel of British political studies, a field not renowned for its ready embrace of radical theoretical positions. Former editor of Political Quarterly, political analyst extraordinaire, and the subject of a special section of PQ’s next issue, Gamble’s Marxist roots are well known, but often dismissed, as if they represented a youthful fad that had little bearing on the content of his work. This confusion arises in part because Marxism remains poorly understood (and thus easily caricatured), but also because Gamble’s theoretical position clearly did evolve away from his Marxist starting point as the politics of the 1980s and 1990s played out. But the character of that evolution was more subtle than a straightforward renunciation, as can be documented in the outstanding two-volume collection of Gamble’s essays recently published by Bristol University Press, After Brexit and The Western Ideology.

On Gamble’s own account, his intellectual formation took place amid the radicalism of the late 1960s and the Keynesian Cambridge economics degree taught by figures such as Joan Robinson and James Meade, though after graduating Gamble spent an important year studying at Durham with a disciple of Michael Oakeshott.[1] Gamble’s first book, co-authored with Paul Walton, was From Alienation to Surplus Value (1972), a study of Marxist ideas for which he and Walton were awarded the Isaac Deutscher Prize (a strong signal of approval from the small but influential network of British Marxist intellectuals at that time). The book concluded that ‘Marx’s theory of capital accumulation, based on his labour theory of value … is still the only theory which provides a completely consistent account of the genesis and reproduction of capitalism.’[2]

The Conservative Nation

Gamble’s first sole authored book, The Conservative Nation (1974), which remains widely read and discussed today, was based on his Cambridge PhD thesis. It was a sign of Gamble’s future research direction in that it provided an incisive anatomy of political debates within the Conservative Party after the Second World War. Gamble recollects that he gravitated to this subject because he wanted to understand the career of Enoch Powell.[3] It is a book that can be read as a history of ideas, but as Richard Vinen notes, Gamble did situate the ideological subject matter of the book in the wider context of capitalist political economy. The Conservative Nation started from the observation that the protean character of capitalism, and the social change it brought in its wake, posed continual challenges to political actors seeking to maintain a market system and its class structure. Those who sought to govern the state in the interests of capital faced endless frustrating negotiations between the diverse interests of property owners on the one hand and shifting popular pressures on the other.

In this initial iteration, Gamble’s famous distinction between a ‘politics of power’ and a ‘politics of support’ was rooted in Marxist analysis: the Conservative Party was ultimately a mechanism by which the public could be mobilised (the politics of support) to uphold a state committed to the defence of private property (the politics of power). However, as Gamble was then at pains to argue, it was never obvious how to develop either a popular appeal or a governmental strategy that achieved this objective, so within these broad structural parameters significant scope existed for political debate about the best compromise that the Conservatives could broker between the contending forces at play in British society. On the one hand, private property and the power it conferred on its owners was the central determining structural fact about a capitalist society like Britain. But on the other, this was a general constraint that left considerable leeway for political agency, requiring skilful political thinking and manoeuvring from Conservative politicians to maintain their party in power.

Britain in Decline

Gamble’s most quintessentially Marxist single authored work, though, was Britain in Decline (first edition 1981), a panoramic account of modern British history that sought both to analyse Britain’s loss of its hegemonic geopolitical and economic status and to identify the strategies that had been mapped out in response by the British political elite. This was a work of remarkable learning and insight, which deserves to be placed alongside analogous writings by figures such as Eric Hobsbawm and Perry Anderson as a wonderful example of how intellectuals reared in the Marxist tradition have raised the analytical standard of debate about Britain’s history and politics.

Gamble used a broadly Marxist methodology, in the sense that he proceeded from a material analysis of Britain as an imperial economic superpower that had become boxed in and over-extended as rival powers became stronger and as tensions within Britain’s industrial economy became more profound. But, in a similar fashion to Anderson’s pioneering essays on British political development in New Left Review, Gamble then pivoted from these material foundations to investigate in detail the intellectual debates that had consumed the British elite in response to these changing economic circumstances. His argument was that British leaders had consistently failed to get to grips with the necessary strategic choices that faced Britain after the 1940s, prioritising overseas entanglements at the expense of internal industrial development.

Gamble concluded the first edition of the book with some sympathetic words about the Labour left’s Alternative Economic Strategy (AES) for at least putting on the table the correct issues. As Gamble saw it, the AES had identified important questions about how British popular sovereignty could take back control from a secretive state apparatus and the economic constraints imposed by global economic integration. Gamble was also moderately sceptical that the Thatcher government, then in its third year in office, would succeed with its strategy of market shock therapy, in part because, like many observers at that time, Gamble believed that modern capitalist societies were structurally trending in a corporatist direction, characterised by larger units of production, high trade union density, and powerful state bureaucracies.[4] The subsequent electoral success of the Thatcher government was no doubt a salutary lesson in the limits of a purely structural analysis of politics.

Gamble and Thatcherism

Gamble’s own research on the Conservative Party in the 1980s famously produced a brilliant and hugely influential treatment of Thatcherism. His ideas were developed initially in articles published in socialist periodicals, the Socialist Register and Marxism Today, before eventually being published as The Free Economy and the Strong State (first edition, 1988). This was a book that emphasised that Thatcherism was the product of the distinctive material circumstances that aligned in the 1970s and 1980s, notably the social tensions produced by the end of the postwar economic boom, but that it also represented a strategic choice that drew on Conservative statecraft and neoliberal ideology. Gamble drew on the Gramsci-influenced concept of ‘hegemony’ that had been adapted by figures associated with Marxism Today, notably Martin Jacques and Stuart Hall, and in that sense Gamble’s depiction of Thatcherism was a powerful expression of the more culturally sensitive Marxism that had emerged from the 1960s New Left. Gamble thought that analysing Thatcherism as a ‘struggle for hegemony’ on the part of the Conservative leadership was a valuable approach precisely because it enabled the aggregation and ranking of several different explanatory factors, encompassing geopolitics, economics, ideology and political strategy.[5] The corollary of that position—evident in the writing of Hall as well—was that Marxism started to look less like a distinctive materialist explanatory framework and more like a pluralist account of social causation that converged with various other historical and social scientific methodologies.

Gamble and neoliberalism

It also became clear during the 1980s and 1990s that Gamble’s encounter with the ideology of neoliberalism—and perhaps the fall of the communist regimes after 1989—had changed his thinking about political economy. One example of this was the rendering of the ‘politics of power’ in less Marxist terms. In the first edition of The Free Economy, one test of the politics of power was certainly presented as ‘does the Thatcher government possess a viable accumulation strategy capable of reversing British decline?’[6] But there was also a drift in the use of the term away from the functionalist Marxist underpinnings attached to the concept in The Conservative Nation towards a more generic idea of government competence and capacity to deliver on policy objectives (the way in which ‘the politics of power’ is generally used today).

Perhaps the clearest evidence of Gamble’s rethinking, however, was in his writings on neoliberal theory, notably Hayek: The Iron Cage of Liberty (1996). Gamble now believed that figures such as Hayek had broadly been proved correct in their diagnosis of classical socialism. As Gamble saw it, the impact of neoliberal theory had been so profound in part because it actually reflected certain fundamental features of modern economies ‘such as the extended division of labour, individual property rights, competition and free exchange, which have to be accepted as givens rather than choices.’[7] There was a touch of the end of history in these remarks, in that Gamble had concluded that there was no feasible alternative model of economic organisation to a capitalist one.

But there was a dialectical twist to Gamble’s coming to terms with certain immutable features of modern exchange economies. While Hayek’s points about the fallibility of human knowledge were indeed fatal for economic planning, Gamble nonetheless saw Hayek’s ideas as much less forceful when it came to a social democratic model of capitalism. On this account Hayek’s liberalism could be absorbed—or, to use the Marxian term, sublated—by a left politics that sought not to abolish markets altogether, but to ensure a more egalitarian distribution of market assets and opportunities.

The persisting relevance of Marxism

In an essay written in 1999, Gamble observed that the persisting relevance of Marxism lay in ‘the claim that the economic power which accrues to the class which controls productive assets is a crucial determinant of the manner in which political, cultural and ideological power are exercised.’ He added that although this point ‘has often been made rather badly, it is a serious claim’.[8] In collaboration with colleagues such as Gavin Kelly, and as part of the ideological ferment that surrounded Labour’s return to government in 1997, Gamble argued that a state that fostered an egalitarian distribution of private property, and undertook reforms to corporate governance to make companies more accountable, could meet neoliberalism head on by taking its aspirations for individual liberty seriously, as a goal that should be universalised and applied to the economic realm as much as any other facet of human existence. This was a move not unlike Marx’s own response to the classical political economy of his day.

The great strength of Gamble’s work has been his unrivalled grasp of each of the different levels of social explanation that are necessary to understand politics. In particular, he has always attended to the importance of Britain’s economic and geopolitical context without short-changing the role of ideology and statecraft in shaping political outcomes. A man of the left, some of his most important work has been devoted to analysing the Conservative Party. This ability to bridge intellectual and political divides is a rare commodity in contemporary academic life. Gamble’s formation in the Marxist tradition was central to these achievements because it oriented his work within the study of historical political economy and provided a critical perspective on capitalism that persisted even after the collapse of the socialist dream of a new economic order. As Gamble put it: ‘It may not be possible to live in the modern world without capitalism, but capitalism need not be a single fate.’[9]

You can read Ben Jackson's full commentary in issue 92 3 (forthcoming).

[1] A. Gamble, ‘Introduction: an intellectual journey’, in Gamble, The Western Ideology, Bristol, Bristol University Press, 2021, pp. 4–7.

[2] A. Gamble and P. Walton, From Alienation to Surplus Value, London, Sheed & Ward, 1972, p. 227.

[3] Gamble,‘Introduction: an intellectual journey’, pp. 7–8.

[4] A. Gamble, Britain in Decline, London, Macmillan, first edn., 1981, pp. 197, 223, 229–31, 233, 237.

[5] A. Gamble, The Free Economy and the Strong State, London, Macmillan, first edn., 1988, pp. 23–5.

[6] Gamble, Free Economy, pp. 35–6.

[7] A. Gamble, ‘The western ideology’ [2009], reprinted in Gamble, The Western Ideology, p. 26.

[8] A. Gamble, ‘Marxism after communism’ [1999], reprinted in Gamble, The Western Ideology, p. 119.

[9] Gamble, ‘Marxism after communism’, p. 120.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley