| 6 mins read

The decades between 1948 and 1980 are often remembered as a time of mass immigration, yet almost 2 million more people left the UK than arrived in those years. The absence of emigration from our common understanding of British political history is surprising considering how socially ubiquitous it has been—and how singular it makes British society. The UK is perhaps unique in world history for experiencing mass exit for over 150 years and for having a state that helped subsidise it for fifty years.

In Britain, the political effects of emigration have been of most interest to Eurosceptic c/Conservatives, who wish to build closer ties with the former Dominions of the British Empire—Canada, Australia and New Zealand to attempt to reinvigorate the UK after Brexit. An examination of what I call the UK’s ‘emigration state’ can help us get a better grip on this politics; contribute to wider public understandings of migration history; transform our understanding of British politics; and help researchers analyse the effects of racism and empire.

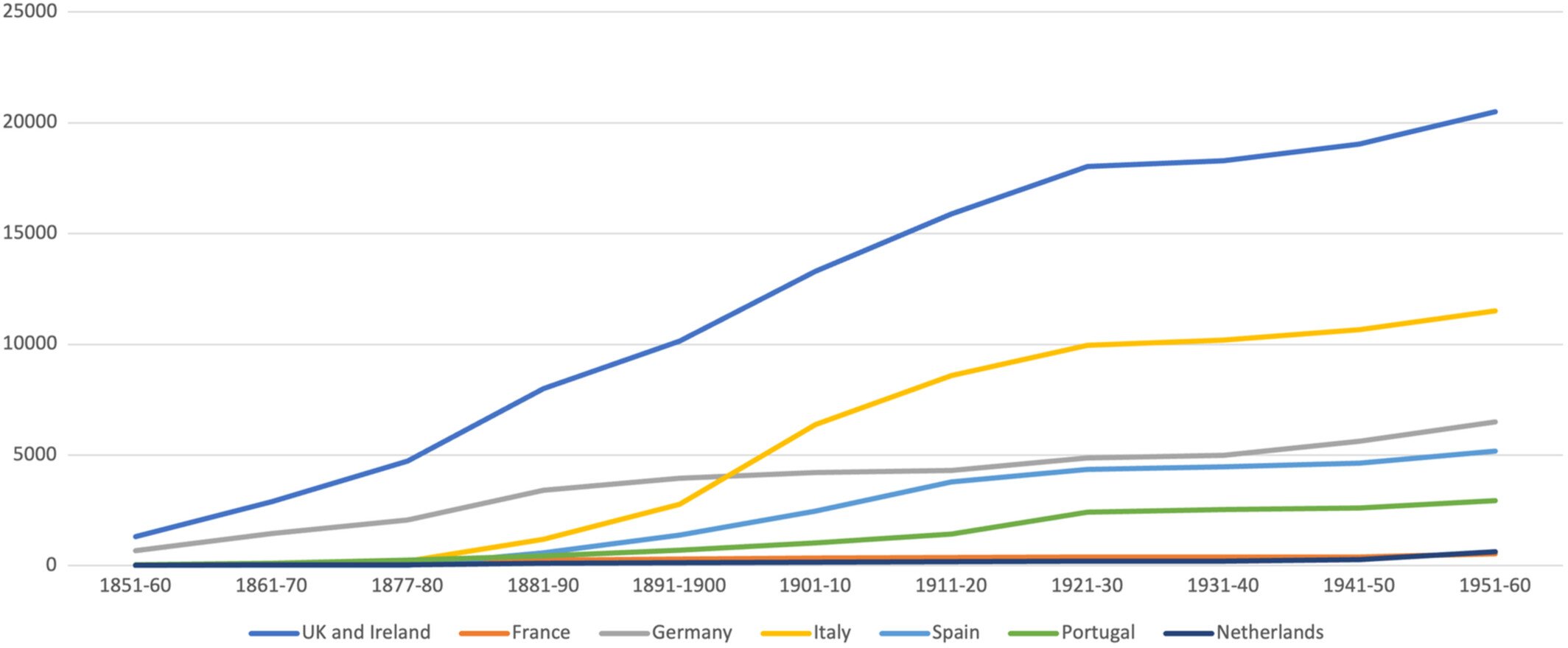

Emigration from the UK and Ireland set them apart from all other west European states (see fig 1). Emigration from France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands and even Italy paled in comparison.

Figure 1

Estimated cumulative emigration from countries in Europe to destinations outside Europe (y axis in thousands; 1850 benchmarked as zero). The data used to make these charts groups UK and Irish migrants together (this is problematic for several reasons—not least because the Irish Free State split from the UK in 1922, and the causes and consequences emigration were starkly different in Ireland and in Britain.

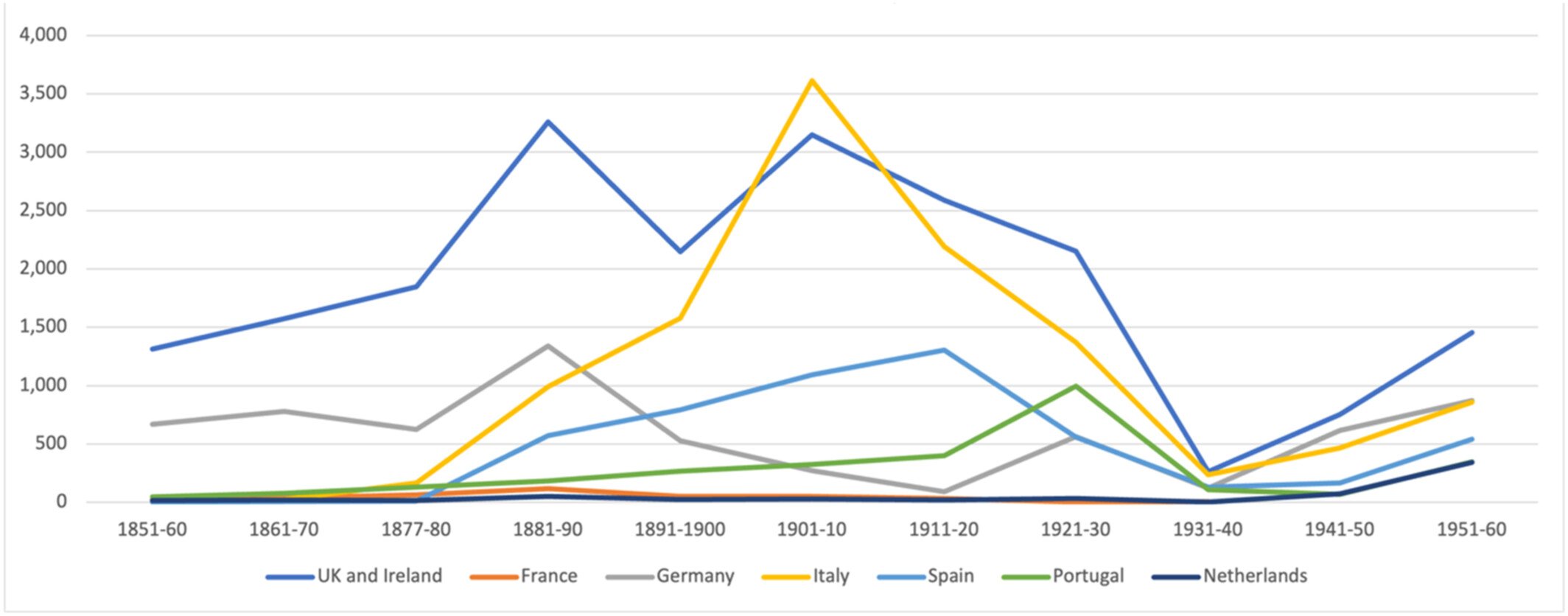

Figure 2: Estimated emigration from countries in Europe to destinations outside Europe by decade (y axis in thousands). Source of data: B.R. Mitchell, International Historical Statistics (1992).

1880 to 1914

The political history of emigration can be split into two periods, defined by the absence or presence of state subsidy.

1880-1914 was an era of laissez faire. Most scholars who have written about emigration from the UK focus on the nineteenth-century ‘white deluge’ of migrants from Europe to the USA, Latin America and Britain’s settler colonies. In this era, emigration was seen by political and social elites as an efficient way to expel the poor, political radicals and social ‘undesirables’. A more ambitious politics of emigration emerged in the 1880s when various pressure groups argued that subsidising emigration away to lead migrants away from the USA to the British Empire might help to maximise the UK’s economic, political and military power. These campaigns were unsuccessful and the vast majority of UK migrants in the second half of the nineteenth century left these islands without financial support from the state.

1914 to 1972

This era of laissez faire ended in 1922. The UK state then subsidised emigration until 1972. By then emigration had become a durable part of UK society and it figured in the making of social policy, economic policy, foreign policy and military planning. The result was the emergence of the UK's ‘emigration state’, a formation which peaked in the 1920s, culminating in the passage of the 1922 Empire Settlement Act before waning during the 1960s.

Connections to the settler colonies were also strengthened by fiscal and monetary policy. Although the UK government and the Dominions offered less financial support for emigration during the global depression of the 1930s, the Empire Settlement Act was renewed in 1937 for a further 15 years.

Migration from the UK after 1945 was huge (see fig 2); between 1945 and 1952, 1,060,000 people left the UK. Over the next two decades successive British governments doubled down on the promise of the ‘emigration state’, extending the Empire Settlement Act multiple times. Subsidies to emigrants were paid out at precisely the time that many other Commonwealth migrants transiting to Britain saw their mobility controlled and their citizenship status changed. Racism was central to these policies.

Why did emigration to the Dominions obsess so many Britons for so long? Emigration was driven in the 1920s by inter-imperial rivalry with Germany, Japan and the USA, and was also seen as a way of solving unemployment. Many of those assumptions still held in the 1960s. Yet, by then, the political and financial commitment to the UK’s emigration state was waning, as more and more politicians steered the UK towards membership of the EEC and away from the former Dominions.

Conclusion

For the past two centuries emigration has affected the UK from top to bottom, playing a constitutive part in making the modern British state.

Once we become attuned to emigration's often unremarked centrality in British politics, we might see its effects either directly or at one remove at key moments of national drama and political change. The two world wars and their aftermaths, the turn to tariffs, joining the EEC and leaving the EU: at these critical junctures, Britain's overseas diaspora was mobilised to reshape domestic politics and to transform the UK's global political economy. The rise, fall and afterlife of Britain's ‘emigration state’ may prove to be a helpful analytical frame to approach these paradigmatic events in British political history with fresh eyes.

There are signs that emigration is once again becoming a matter of concern in the UK’s political culture as many citizens look to make better lives abroad outside the UK's sphere of influence. This means that emigration may soon re-enter public and political debate, but unlike in the 1920s now as a sign of national weakness rather than imperial strength.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley