| 7 mins read

The 2014 Scottish independence referendum settled little in terms of Scotland’s constitutional future. Following Brexit and continuing disagreements between the Westminster and Scottish governments, there have been increasing demands for a second referendum. Scots living outside Scotland would certainly find their relationship with their home nation impacted Scottish independence, so should they have voting rights?

We conducted two online surveys, of members of the diaspora returning to Scotland and of Scots living in England following Brexit, exploring attitudes to independence. These showed considerable divergence on how to define eligibility for diaspora voting rights, but that the diaspora retains a strong sense of Scottish identity.

THE INDEPENDENCE REFERENDUM FRANCHISE

The franchise for the 2014 referendum was settled by the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013. The vote was given to all EU citizens then residing in Scotland, excluding anyone previously resident in Scotland no longer on the electoral register, and 16- and 17-year-olds. The UK government believed it was essential to start from a pre-existing franchise to avoid a perception of seeking to influence the result. Thus, the franchise was essentially the same as for the 1997 Scottish devolution referendum. The disenfranchisement of ‘non-resident Scots’ was perhaps the only workable position, since drawing up a register based on either birth or previous residence in Scotland would have been exceptionally difficult and probably inaccurate.

SHOULD THE DIASPORA HAVE A VOTE?

In Scotland, there has been continuing debate around voting rights. Some believe that those who would be eligible for citizenship in a future independent Scotland should have voting rights. But this would rely heavily on rights being granted according to bloodline.

Others believe that excluding ‘blood nationals’ is a requirement of liberal democracies. Some Westminster politicians have suggested that Scots living elsewhere in the UK should be given a vote, though this has led to accusations of ballot rigging, making a unionist victory more likely. The 2014 British Election Study asked voters across the UK how they would vote in an independence referendum and showed that, of 381 people born in Scotland but living in England or Wales, 78% would vote No and only 22% indicated Yes. The same survey showed that 57% of Scottish voters planned to vote No and 43% Yes. This showed a twenty-point difference between support for independence within Scotland and Scots-born living elsewhere.

Currently, if Indyref2 is held, the Referendums (Scotland) Act 2020 would apply. The Electoral Commission would have a statutory role, overseeing the poll’s conduct, the regulation of referendum campaigners and testing the proposed question. The 2020 act provides that the franchise for any future referendum will be the same as that for Scottish parliamentary elections, meaning that anyone aged 16 or over, who is legally resident in Scotland regardless of nationality and who is on the Scottish local government electoral register, would be entitled to vote. As in 2014, this would exclude Scots living permanently outside Scotland.

A SECOND REFERENDUM: VIEWS FROM THE DIASPORA

We conducted two online surveys, of members of the diaspora returning to Scotland and of Scots living in England following Brexit, exploring attitudes to independence. We received 54 responses, recognising of course that this is in no way a large or representative sample.

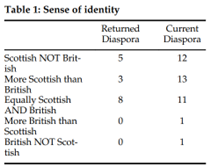

Of our 54 respondents, 16 had returned to live in Scotland, while a further 38 were still living outside. All but one were born in Scotland, while, of those still living within the diaspora, 20 were born in Scotland, 14 in North America, 2 in England and 2 elsewhere. We interviewed 26 men and 28 women. Table 1 shows the responses on national identity. Only two respondents (both currently within the diaspora) prioritised their British identity, so there was a strong sense of Scottishness.

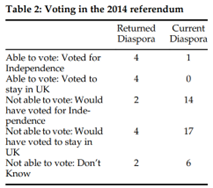

We then asked how they had or might have voted in 2014, as shown in Table 2. Excluding the ‘Don’t Knows’, the ‘vote’ splits 25–21 supporting remaining in the UK. This 54-46 per cent divide almost exactly mirrors the actual referendum result.

In terms of voting rights, we found that views were quite divided. When asked if Scots living abroad should be able to vote in an Indyref2, only 4 returners believed this appropriate. Current diaspora members, perhaps unsurprisingly, felt differently with 23/38 respondents believing they should have voting rights. Those rejecting diaspora voting suggested ideas that only those subject to the running of that country should be allowed to vote, linking with notions of ‘no taxation without representation’. Meanwhile, those in favour of diaspora voting mentioned things like ‘I am Scottish, no matter where I live’ and other emotional attachments to Scotland. There was considerable divergence on how to define eligibility for diaspora voting rights.

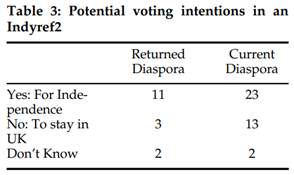

Finally, we asked individuals how they would vote in an Indyref2 were one to be held. There had been a significant shift in opinion since 2014, as shown in Table 3. Thirty-four respondents stated they would now vote for independence. The main reason for this shift seems to be Brexit, as a large Scottish majority voted to remain in the EU. Thirteen people specifically referenced Brexit and ten mentioned the failings of the Westminster government.

CONCLUSIONS

There is no absolute right for all members of the Scottish diaspora to vote. Hopefully the very small-scale exploration presented here may lead to a larger-scale research effort. We must stress that more research is required and would not wish to exaggerate our findings. The sample size is limited, and in-depth face-to-face interviews were not conducted. Nonetheless, our findings reveal the diaspora retains a strong sense of Scottish identity. While the returned diaspora mostly believed that Scots remaining overseas should not have voting rights, a majority of the current diaspora unsurprisingly resented being excluded from voting, but the eligibility question is unresolved. Therefore, we would conclude the Scottish government is correct to define the franchise by residence rather than by bloodline.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley