| 9 mins read

In her review of the Metropolitan Police following the abduction, rape and murder of Sarah Everard by a serving police officer, Baroness Casey found misogyny internally and externally, findings which were reinforced in the Angiolini Inquiry report. Such behaviour is not exclusive to particular police forces.

Sexism and misogyny are by no means unique to policing. We do, however, expect policing to be held to the highest standard given the unique powers officers hold.

CoP has applied a behavioural science approach to cultures of sexism and misogyny in policing. This is not about characteristics of individual officers, nor solely occupational culture. Instead, by understanding when and why people act in a certain way, a package of targeted and effective interventions can be designed to change behaviour.

Behaviours associated with sexism and misogyny

To build a comprehensive understanding of what sexism and misogyny looks like in a policing context, 452 sources of evidence were screened, including academic publications and grey literature.

A total of 220 behaviours relevant to sexism and misogyny were identified from the literature and workshop. These included a gendered division of labour, such as female officers being tasked with supporting sexual assault victims; acts of a sexual nature directed at female officers and staff; witnesses to inappropriate behaviour staying silent or showing loyalty to the instigator, and ostracising those who challenge or report sexist or misogynistic behaviour.

officers and staff consulted as part of this work felt everyday sexism’ should be targeted to instigate a cultural shift. As such, four behaviours were prioritised.

- Officers and staff not exhibiting everyday sexism or misogyny in the workplace. This includes (but is not limited to) not commenting on how women got promoted or undermining women in leadership positions, not using sexist or demeaning language or nicknames, not sharing offensive jokes.

- Supervisors having conversations when they witness or become aware of indicators which suggest sexism and misogyny is occurring within their own teams. Conversations should be constructive, proportionate and encourage reflection.

- Colleagues acting when they witness everyday sexism and misogyny in the workplace. This includes (but is not limited to) behaviours such as telling the instigator it wasn't appropriate in the moment or soon after, actively disengaging from sexist conversations, jokes and messages, or changing the subject, asking the victim if they need support in the moment or soon after, taking the victim out of the situation, and seeking advice from others.

- Victims of sexism and misogyny in the workplace raising the behaviour with their supervisor, HR, PS, or via other official channels where appropriate. It is important to note that it should not be the responsibility of victims to improve the behaviour of others. But, by including this as a target behaviour, it creates a focus on the barriers women in policing face in feeling safe enough to raise concerns.

The behavioural diagnosis

The COM-B model states that for any behaviour to occur, the person must be psychologically and physically capable of doing it; have the physical and social opportunity to do it; be more motivated to do that thing at that moment than any other competing behaviour.

influences that were preventing or enabling the four target behaviours to happen.

Beliefs about consequence (motivation)

A major barrier that emerged from the evidence was the justified belief that there would be negative repercussions for speaking up against sexism.

Emotions (motivation)

Fear of upsetting others, embarrassment arising from getting things wrong and even guilt about jeopardising others’ career opportunities can inhibit staff from acting.

Trust in the process (motivation)

Those experiencing unacceptable behaviour and those witnessing it did not trust that reports of sexism would be dealt with objectively or lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Role-modelling of expected behaviour (opportunity)

Evidence indicated that police leaders need to model expected behaviours and demonstrate to colleagues that they will be supported if they raise concerns.

Social expectations (opportunity)

Evidence suggested that everyday sexism and tolerance of it is commonplace within policing.

A culture of solidarity (opportunity)

Solidarity is embedded in the culture of policing and an important part of what makes policing effective. However, solidarity can result in protection of the instigators of unacceptable behaviour.

Ability to identify and respond appropriately to everyday sexism (capability)

The evidence suggested that officers and staff do not always recognise sexist behaviours, particularly the more subtle, everyday behaviours.

Interventions for change

The intervention design process was based on three evidence sources: REF the article

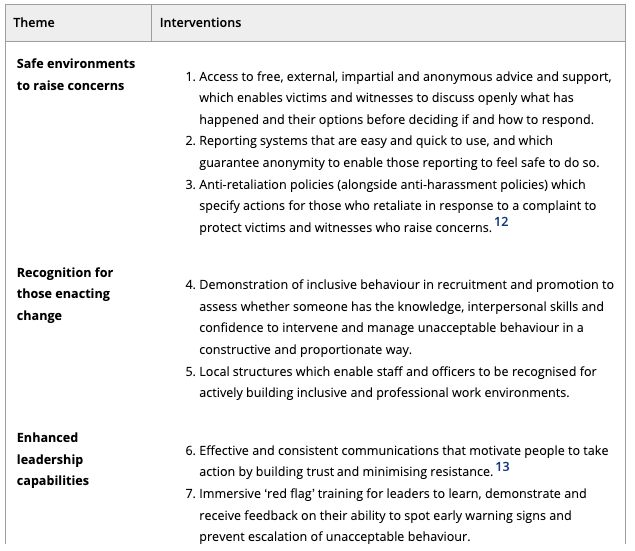

Combined, this led to the generation of 206 intervention options across the four target behaviours, which were then clustered into twelve bundles based on commonalities.

The twelve interventions were shared with approximately twenty-five police officers and staff of different genders and ranks. Feedback was used to refine the interventions. The twelve interventions were grouped across four themes as follows.

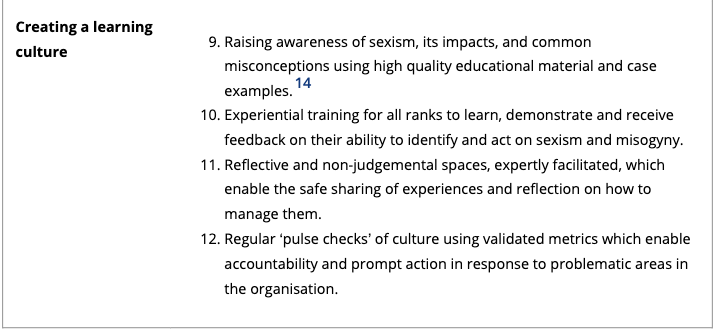

Figure 1. The relationships between behaviours, influences and interventions to tackle sexism and misogyny (SAM).

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the behaviours, COM-B influences and proposed interventions. The arrows demonstrate which interventions are acting on the seven capability, opportunity and motivation influences, and in turn which influences need to change to increase the likelihood of the four target behaviours occurring. The image is a simplification, as it would be too intricate to include all the influences and the connections between them. The diagram helps to depict how multiple interventions are needed to change a single behaviour. Each of the behaviours have at least three different influences driving them. For example, for supervisors to act on early indicators of sexism and misogyny, they need the capability to identify and respond appropriately, the opportunity to see their own leaders modelling the behaviour, and a low level/no fear or embarrassment about doing so (motivation). For those three influences to change, multiple interventions are needed, including: immersive ‘red flag’ training; regular ‘pulse checks’ of culture; and expertly facilitated reflective spaces underpinned by evidence-based models

If focussing on the behaviour of victims raising or reporting unwanted behaviour, they need to trust that the reporting process is objective, effective and confidential (motivation), and believe they will be able to carry on with their job without experiencing negative repercussions (motivation). Three interventions directly linked to these influences are: access to external and impartial support; anonymous reporting systems; and organisational policies that protect from retaliation.

Like victims, for witnesses to raise concerns, they also need to be able to trust that unprofessional behaviour is not accepted nor part of the identity of policing. Interventions directed at witnesses include a combination of experiential training to acquire knowledge and skills; communications which aim to shape social norms within policing; and a requirement to demonstrate inclusive behaviour as part of recruitment and progression.

Whether the interventions need to be implemented as a package to change culture by targeting different points in the system. This helps avoid a ‘whack-a-mole’ approach to tackling culture change.

Conclusions

Much focus continues to be on improving vetting processes and ways to remove those from policing who fall well below the expected standards of behaviour. While this is undoubtedly needed, we must not forget the everyday behaviours that perpetuate cultures of sexism and misogyny. There is no quick or easy fix to deeply ingrained issues such as these, but long-term commitment is needed to eradicate sexism and misogyny from policing once and for all.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley