| 7 mins read

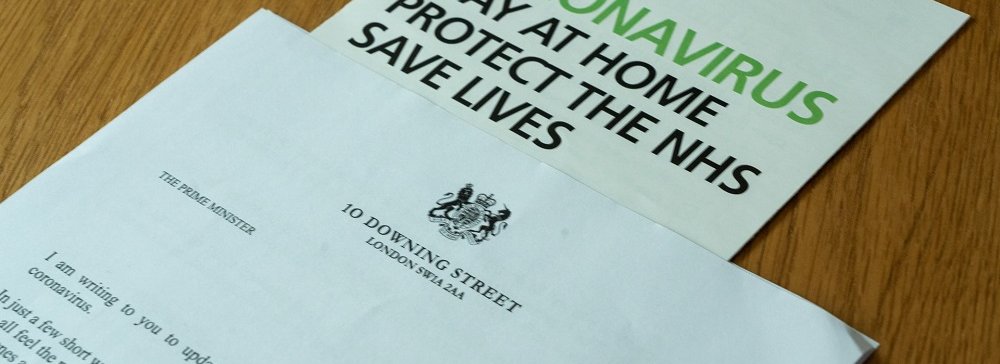

How the British government has communicated with the public and what it has communicated have played a major part in determining how citizens have behaved during the Covid‐19 pandemic.

Secrecy

A background factor in the official Covid‐19 information campaign is a long‐established tradition of secrecy in British government.

Over the last decade, several guarded simulations were run to test the country’s ability to deal with a pandemic, including Exercise Cygnus in 2016. All found serious failings in current policy provisions, and among their recommendations they picked out the need to stockpile equipment and the need to shield those most at risk in care homes.

Little was known about Exercise Cygnus until it was leaked in 2020, but it seems that its publication was suppressed because it was ‘too terrifying’ for the public.2 Care homes, too, were not informed of its recommendations, so they could not implement them in 2020.

Government secrecy caused further distrust by keeping the membership of SAGE and its individual members’ views confidential. Under pressure, the government revealed SAGE membership to the public. Records showed that there were disagreements about several courses of action - some heeded by the government, some not. Concern was expressed when it was discovered that the Prime Minister’s policy advisor, Dominic Cummings, had attended its meetings.

Government misinformation

Government misinformation was frequent during the British pandemic.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, announced that over a billion items of PPE were being delivered. It later transpired that the billion included many items not usually thought of as PPE (such as body bags) and surgical gloves were counted singly, not in pairs. The figure of a billion was an overestimation by many millions.

Covid testing produced further misinformation. Daily tests increased slowly until a goal of 100,000 tests a day by the end of April was announced. When the day arrived, it was claimed that the target had been exceeded by a substantial margin, but the figure included tests that had been put in the post - whether they had been carried out or processed was unknown.

One of the more puzzling events occurred when, in April, Boris Johnson caught the virus and went into intensive care. However, it was announced that he was in an optimistic mood and still in charge of government. Shortly after, a press release said the PM had recovered enough to be able to sit up in bed. It is not clear how someone can be in good spirits and running the government one day, and the next day, improved enough to sit up in bed.

Mainstream media information

The British public took a close interest in Covid‐19 from the start. Four Populus surveys from 20 March to 10 April recorded a record breaking 98 per cent of the population noticing stories about the virus.28 The mainstream media covered the pandemic extensively, with the press investigating and correcting government misinformation. Consequently, the public was well informed in general about the pandemic and how the government was dealing with it.

The evidence is that people make up their own minds about subjects that are of personal relevance and about which they have personal experience and knowledge.31 The combination of unreliable government information, counter‐balanced by reports from the mainstream news media, plus the population’s inclination to make up its own mind about issues of first‐hand relevance, influenced trust in the government and compliance with lockdown rules.

Attitudes and social behaviour

Attitudes

From the end of January 2020, government approval climbed from 30 per cent to a peak of 52 per cent on 23–23 March, when it fell to 32 per cent by the first week of June. Similarly, trust in the government to provide accurate pandemic information fell from 67 to 48 per cent between 10 April and 21 May.34 By the end of May, the Conservatives were, in the words of a YouGov poll, taking a hammering.35

In other countries, those politicians with reputations intact or enhanced during the Covid crisis have been notable for their frank discussion of the difficulties of policy making. They have been disproportionately women, including Jacinda Ardern and Nicola Sturgeon. By comparison, British ministers—almost exclusively men—failed to engage the trust of the general public. The government relied on upbeat messages; the public wanted plain speaking that confronted reality.

Social behaviour

The great majority of people complied with social distancing, shielding, and lockdown rules; some took the decision days or even weeks before the government acted. Why? Because, as argued above, they used different sources of information and made up their own minds about how to protect themselves and those around them.

Three‐quarters of the population believed that they could personally influence whether or not they became infected.41 If the crisis is perceived to affect the personal interests of an individual, or their personal safety and that of their friends and family, they are likely to weigh up the risks and take what action they think is appropriate.

Conclusion

It is widely assumed that compliance with social distancing and lockdown rules require a trust in the transparency of government. However, the British public generally observed the rules, despite a major decline of confidence in government, in the space of just a few weeks. It did so because it had alternative and more trusted sources of information in the mainstream news media and the non‐government expert opinion that the media reported.

Perhaps most importantly, there is evidence that public opinion is less susceptible to influence by the government or the media in matters of personal impact. Covid‐19 posed a personal threat to health and life, and hence people generally formed their own opinions about it, how the government had handled it, and what actions they should take to protect themselves.