| 6 mins read

On 17 October 2019, a proposed WhatsApp tax fuelled the largest protests Lebanon has seen in more than a decade. In a month where the government failed to deal with one crisis after another – including unprecedented wildfires – a proposal to charge £4.50 a month for using voice calls on WhatsApp brought widespread anger to boiling point.

Protesters took to the streets and blocked major roads. They called for an independent, non-sectarian government and a complete overhaul of the country's political system. The backlash caused the government to quickly retract the proposal, but it was too late to stem the tide of political discontent.

Few expected such a protest movement to break out in a small state riven by divisions, but there are deeper undercurrents that explain why the protests in Lebanon are happening.

Political alienation since the civil war

Faithful to an unwritten 1943 National pact, the Lebanese political system pivots around an executive coalition in which the president is a Christian Maronite, the Prime Minister Sunni and the Speaker of Parliament Shia.

After a 15-year long civil war (1975-1990), sectarianism in Lebanon has remained immune to reform. Sectarian warlords hold on tightly to power, while the gap between elite-led politics and citizens has been widening year on year.

The onset of Syria’s 2011 war has turned Lebanon into a playground for regional divisions. This has added much strain on the flimsy consensus that prevails among politicians in its sectarian government. Moreover, rampant corruption, clientelism and the state’s inability to provide basic services such as electricity and trash collection have deepened feelings of alienation.

Widespread dissatisfaction

In the context of the 2011 Arab Spring, analysts have generally portrayed Lebanon as resistant to the uprisings that have engulfed the region. They have cited reasons such as post-war fatigue, and the fear of (re)enacting grim scenarios that have superseded the 2011 Arab protests.

However, according to many surveys, the Lebanese are one of the most highly dissatisfied citizenries worldwide. They mistrust the so-called ‘sectarian gatekeepers’ who rule in the name of perpetuating stability in a turbulent region. Indeed, Lebanon is known for its population’s high propensity to emigrate.

With all this in mind, there are four reasons why the protest movement comes as no surprise.

1. The ‘roots of rage’ are lurking beneath

‘Roots of rage’ are what usually spark uprisings. And they have been visible in the everyday practices of Lebanese citizens for decades. Long before the proposed WhatsApp tax, people have expressed continuous dissatisfaction with inept governance, a deteriorating infrastructure and lack of access to public services.

However, there is something else that characterizes the protest movement this time. Namely, the fact that Lebanese protesters, just like Tunisians prior to the fall of the Ben Ali regime in 2011, are deeply convinced that they will remain the disenfranchised ‘others’ while their political class grows richer and richer.

Protestors in Lebanon

2. The machinery of change is ready

Meaningful protest movements build on a legacy of activism. Lebanon’s 2019 movement certainly does this. Although trade unions and interest groups have been weakened and politicized, Lebanon still has one of the most vibrant civil society landscapes in the Middle East. As a result, local civil society organisations, persistently calling for change, have harvested small but significant gains.

Moreover, the Lebanon protest movement is not born in a vacuum. The 2015 #YouStink movement denounced the Lebanese government’s inability to solve a massive garbage crisis. This, and other episodes of contention, have instilled a legacy of activism that pervades the public consciousness.

3. A window of opportunity is open

As social movement theorists like to say, grievances are everywhere but opportunities are not. Prior to this moment, Lebanese citizens’ grievances were substantial. But on their own they were not sufficient to sustain a longer-term movement.

But over the past few decades, citizens have seen their leaders squabble, form volatile alliances, and reiterate empty promises. After parliamentary elections had been postponed twice, Lebanese voted in 2018 for the same sectarian-based parties who had vowed to enact major reforms, only to see them drag the country into a major economic recession. Now, protesters have identified an opportunity for change.

Protestors in Lebanon

4. It is not an isolated phenomenon

Lebanon’s protest movement is not an isolated phenomenon. In fact, it is part of a global site of contention where market economies and fallacies of political rule are being renegotiated.

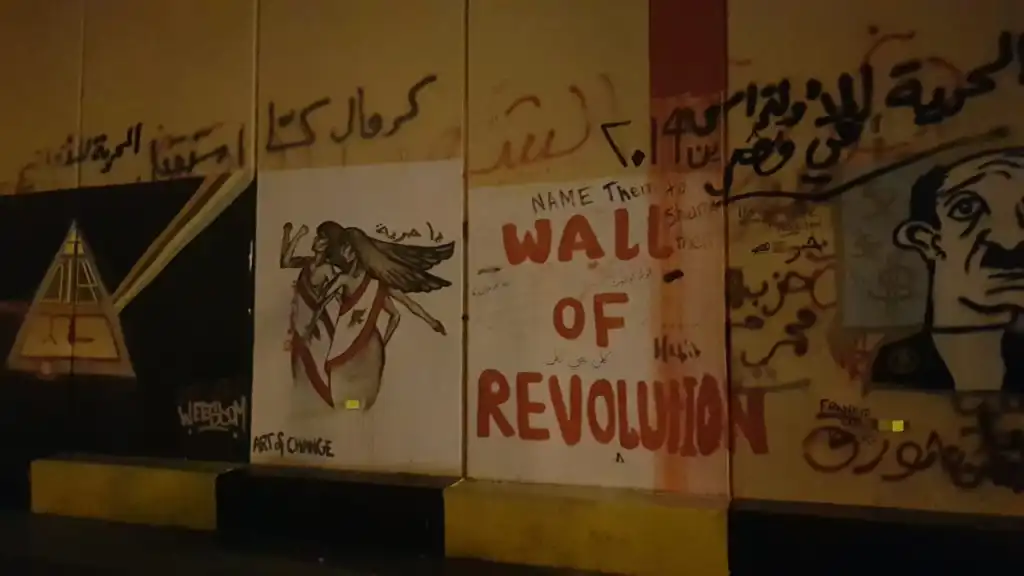

Lebanese protests have managed to gain wider resonance. Through performances, chants and imagery that build on comedy and satire, these protests have struck a chord in the Middle East and further afield.

Protesters have also borrowed from slogans that Tunisians and Egyptians chanted during the 2011 uprisings. For example, ‘silmiye silmiye’ (peaceful peaceful) and the ‘people want the fall of the regime’ have both been used at protests. Moreover, there are traces of the Occupy Movement and its decries of neoliberalism.

Whether the protest movement in Lebanon sparked by a WhatsApp tax will lead to the fall of the regime or not, it certainly resonates with a cascading protest wave spreading from Hong Kong, Sudan, Algeria, Iraq, to Chile.