| 58 mins read

SUMMARY

- Following an electoral catastrophe for Labour, where a minority government led by Ramsay Macdonald had collapsed under the impact of the economic slump of 1931, in 1932 R.H. Tawney set out to describe the choice before Labour.

- Tawney argues that the Labour party had to decide what it was for: securing material improvements for its supporters within the overarching framework of a capitalist system, or creating a new system altogether, which he called a 'Socialist Commonwealth'.

- Underlying this was the question: ‘who is to be master?’ Was society to be dominated by bankers, industrialists and landowners, or will it ‘distribute the product of its labours in accordance with some generally recognised principles of justice?’

- The latter, Tawney suggests, involves fleshing out the notion of a Socialist Commonwealth.

Part One

Now that the dust has settled, it is possible to examine the landscape Left by the earthquake. The election of 1931 was, by general consent, a considerable sensation. But neither the preliminary maneuvers described by Lord Passfield, nor the methods adopted during the contest itself, are the phenomena on which to-day it is most profitable for a member of the Labour Party to reflect. Political coroners may sit on the corpse of the late Cabinet, but the ordinary citizen is more concerned with its behaviour before life was extinct. What matters to him, and what is likely to determine his attitude when next the Labour Party appeals for his support, is less the question of the circumstances in which the last Government went out, than that of what it did, attempted, and neither did nor attempted to do, when it was in. It is possible that his verdict on its death, if at this time of day he paused to consider it, would be, neither murder nor misadventure, but pernicious anaemia producing general futility.

For the events of the late summer of 1931 were the occasion, rather than the cause, of the debacle of the Labour Party. In spite of the dramatic episodes which heralded its collapse, the Government did not fall with a crash, in a tornado from the blue. It crawled slowly to its doom, deflated by inches, partly by its opponents, partly by circumstances beyond its control, but partly also by itself. The gunpowder was running out of it from the moment it assumed office, and was discovered, on inspection, to be surprisingly like sawdust. Due allowance must be made, no doubt, for the cruel chance which condemned it to face the worst collapse in prices of modern history; and due credit must be given for the measures which it introduced, but failed, through no fault of its own, to pass into law. But, granted the inexorable limits, can it seriously be argued that it was audacious in working up to them?

The commonest answer to that question was given in two words: minority Government. To the writer it appeared at the time, and appears to-day, unconvincing. When the Cabinet took office, two alternatives were open to it. It could decide to live dangerously, or to play for safety. It could choose a short life, and–if the expression be not too harsh–an honest one; or it could proceed on the assumption that, once a Labour Government is in office, its primary duty is to find means of remaining there. If it acted on its principles, it could not hope to survive for more than twelve months. It could postpone its execution, but only at the cost of making its opponents the censors of its policy. It would invite them, in effect, to decide the character of the measures which it should be permitted to introduce, and to determine the issues of the next election.

The late Government chose the second course. It chose it, it must in fairness be admitted, with the tacit approval of the great majority of the party, including, as far as is known, those trade union elements in it which afterwards revolted against the results of the decision. The effects of its choice were, however, serious. Parts in life, once adopted, develop their consequences with a logic of their own, over-riding the volition of the actors cast for them; however repulsive, if played at all, they must be played with gusto. Once convinced that discretion was their cue, ministers brought to the practice of the golden mean a conscientious assiduity almost painful to contemplate. They threw themselves into the role of The Obsequious Apprentice, or Prudence Rewarded, as though bent on proving that, so far from being different from other governments, His Majesty's Labour Government could rival the most respectable of them in cautious conventionality.

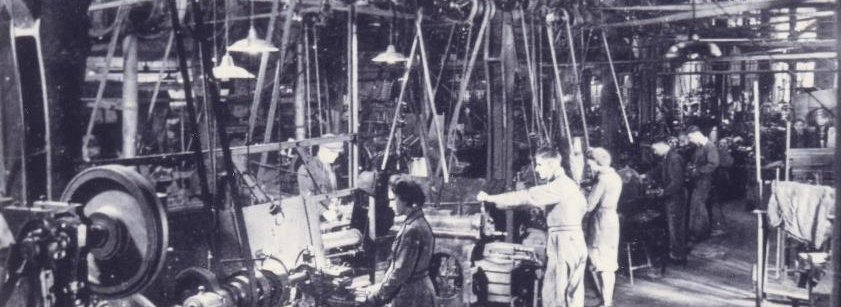

Industrial and social reconstruction, the favourite theme of Labour orators, owed little to the existence of a Labour Cabinet. It doubtless felt itself precluded, till the Macmillan Committee had reported, from making up its mind on the questions of currency and credit which were to prove its undoing. Even in matters, however, where delay was not imposed by circumstances, its action did not err on the side of trenchancy. It found coal, cotton and steel with one foot in the nineteenth century; it left them there. What passed in its inner councils is, of course, unknown; but it gave few outward symptoms of realising that, if the modernisation of the major industries is to be handled at all, it must be planned as a whole, or of grasping the necessity of creating a permanent organ to press it steadily forward, or of appreciating the importance of devoting attention to the long-range aspects of unemployment, as distinct from monthly fluctuations in the number of unemployed. It had even to be stimulated by the protests of its followers in the House into proceeding–too late–with its little Education Bill. In one sphere, indeed, that of international policy, it achieved, in the opinion of good judges, solid and genuine successes. Apart from that important exception, and from the fact that, if King Log was bad, King Stork would be worse, what strong reason could be advanced for desiring its survival?

The degeneration of socialist parties on assuming office is now an old story. If it is worth while to recall the latest British version of it, it is not in order to visit on individuals collective shortcomings. It is because, till its lessons are learned, the wretched business will go on. If the laments of some ex-ministers at the "conspiracy," which "stabbed them in the back"–as though a Titan, all energy and ardour, had been felled at his forge by the hand of assassins–were merely undignified, they would properly be ignored. Unfortunately, they are worse. What Labour most needs is not self-commiseration, but a little cold realism. These plaintive romancers would dry its tears with a tale of Red Riding Hood and the wicked wolf. They retard the recovery of the party by concealing its malady. They perpetuate the mentality which requires to be overcome before recovery can take place. The sole cure for its disease is sincerity. They offer it scapegoats.

If it is sincere, it will not be drugged by these opiates. It will not soothe the pain of defeat with the flattering illusion that it is the innocent victim of faults not its own. It is nothing of the kind. It is the author, the unintending and pitiable author, of its own misfortunes. It made a government in its own image; and the collapse of the government was the result neither of accident-though that played its part–nor of unfavourable circumstances–though luck was against it-nor, least of all, it must be repeated, of merely personal failings. It was in the logic of history; for 1929-31 repeated 1924. It sprang from within, not without; for it had begun within six months of the Government's return, and the flight from principles was both earlier and more precipitate than the flight from the pound. It was the consequence, not of individual defects, but of a general habit of mind and outlook on affairs which ministers had acquired long before they could anticipate that power would be their lot. What was tried, and found wanting, in short, in 1929-31, was, not merely two years of a Labour Cabinet, but a decade of Labour politics.

Such, and not merely the events of a few weeks last summer, were the cause of the debacle. If these are the realities, to make the conduct of individuals, however odious in itself, the main target of criticism is to exaggerate their importance. To expel a person is not to exorcise a sprit. The truth is simpler and more serious. In the swift growth of the movement since 1918, its inner flaws had been concealed. But they had not disappeared; indeed, some of them had deepened. At the moment when the reality of power seemed almost within its grasp, its old faults found it out. It now has an interval in which to meditate its errors.

Part Two

The gravest weakness of British Labour is one which it shares with the greater part of the world, outside Russia, including British capitalists. It is its lack of a creed. The Labour Party is hesitant in action, because divided in mind. It does not achieve what it could, because it does not know what it wants. It frets out of office and fumbles in it, because it lacks the assurance either to wait or to strike. Being without clear convictions as to its own meaning and purpose, it is deprived of the dynamic which only convictions supply. If it neither acts with decision nor inspires others so to act, the principal reason is that it is itself undecided.

This weakness is fundamental. If it continues uncorrected, there neither is, nor ought to be, a future for the Labour Party. A political creed, it need hardly be said, is neither a system of transcendental doctrine nor a code of rigid formulae. It is a common conception of the ends of political action, and of the means of achieving them, based on a common view of the life proper to human beings, and of the steps required at any moment more nearly to attain it. A movement, like an individual, cannot build its existence round an internal vacuum. Till the void in the mind of the Labour Party is filled-till interests are hammered by principles into a serviceable tool, which is what interests should be, and a steady will for a new social order takes the place of mild yearnings to make somewhat more comfortable terms with the social order of to-day-mere repairs to the engines will produce little but disillusionment.

There is much criticism at the moment of organisation and programmes. Some of it, like that which ascribes the troubles of the party to its trade union connections, is misconceived. It is obvious that the unions, like other elements in English society, including the intelligentsia, are most imperfectly socialised. It is obvious that the weight which is given them at party conferences by the card vote is an anomaly, which has a historical justification, but is not permanently defensible. The picture, however, of torpid and rapacious trade unionists impeding bold schemes of constructive statesmanship is a caricature; it cannot truly be said that the late Government was harassed by recurrent pressure to sacrifice the larger aims of the movement to the sectional interests of one element in it. Some of the criticism, again, like the recoil of some members of the party from the social services-as though to recognise unemployment pay for the sorry makeshift it is involved repudiating the communism of Public Health, Housing and Education–is a mood of reaction, engendered by defeat, which in time will pass. But much of it is justified. The only comment to be made on it is that it does not go far enough.

Of course the programme of the party needs to be modernised; of course its organisation requires to be overhauled. No one who knows how the former is made and the latter works is likely to remain long on his knees before either. But, granted the obvious weaknesses of both-granted the intellectual timidity, conservatism, conventionality, which keeps policy trailing tardily in the rear of realities, and over which, if one's taste is for brilliance on the cheap, it is so easy to make merry–the root of the matter is elsewhere. These defects are the symptoms, not the source, of the trouble. They are, not causes, but effects.

The characteristic vice of the programmes of the party, as set out in conference resolutions, is that too often they are not programmes. They sweep together great things and small; nationalise land, mines and banking in one sentence, and abolish fox-hunting in the next; and, by touching on everything, commit ministers to nothing. The characteristic defect of its practical procedure is its tendency to rely for success on the mass support of societies, and the mass vote of constituencies, of whom neither have been genuinely converted to its principles. It requires an army. It collects a mob. The mob disperses. That is the nature of mobs.

But why are Labour programmes less programmes than miscellanies–a glittering forest of Christmas trees, with presents for everyone, instead of a plan of campaign for what must be, on any showing, a pretty desperate business ? Because the party is at present without any ordered conception of its task. Because it possesses in its own mind nothing analogous to what used to be called, in the days when it was necessary to put jobs through to time, a Scheme of Priorities. Because it has no stable standard of political values, such as would teach it to discriminate between the relative urgencies of different objectives. Because, lacking such a standard, it lacks also the ability to subordinate the claims of this section of the movement or that to the progress of the whole, and to throw its whole weight against the central positions, where success means something, and failure itself is not wholly a disaster, instead of frittering away its moral in inconclusive skirmishes.

And why is the Labour Party's organisation, in spite of its admirable personnel, stronger in numbers than in quality? For precisely the same reason. Because the finest individuals are nothing till mastered by a cause. Because the party, being itself not too certain what that cause is, has found it difficult to present it in a form convincing to plain men, of whom the majority, in England as elsewhere, are not politicians. Because, instead of stating its faith, undiluted and unqualified, and waiting for their support till, with the teaching of experience, which to-day teaches pretty fast, they come to share it, it tried to buy their votes with promises, whether they shared that faith or not. Because it appealed to them, on the ground, not that a Labour Government would be different from other governments, but that it would be a worthy successor to all British governments that had ever been. Because, when it ought to have called them to a long and arduous struggle, it too often did the opposite. It courted them with hopes of cheaply won benefits, and, if it did not despise them, sometimes addressed them as though it did. It demanded too little, and offered too much. It assured them that its aim was the supersession of capitalism, but that, in the meantime, the two-hooped pot should have four hoops. Is it surprising if they concluded that, since capitalism was the order of the day, it had better continue to be administered by capitalists, who, at any rate-so, poor innocents, they supposed-knew how to make the thing work?

These, it will be replied, are hard sayings. They are; but, unfortunately, they are true. The inner state of the movement has been concealed from itself by the glamour of a word. That word is Socialism. In 1918 the Labour Party finally declared itself to be a Socialist Party. It supposed, and supposes, that it thereby became one. It is mistaken. It recorded a wish, that is all; the wish bas not been fulfilled. If it now disciplines itself for a decade, it may become a Socialist Party. It is not one at present. Until it recognises that it is not Socialist, it is not likely to become Socialist. Like any other creed, socialism has two aspects. It implies a personal attitude and a collective effort. The quality of the latter depends on the sincerity of the former.

The collective effort involves three essentials: agreement as to the kind of society which it is desired to establish; agreement as to the nature of the resistance to be overcome in establishing it; agreement as to the technique, the methods and machinery, required for its establishment. The history of British socialism, during the present century, is largely the story of the concentration of attention on the third requirement, to the neglect of the two first.

The effort devoted to questions of method has, in itself, been admirable. But expedients require, in order that they may be applied, and produce, when applied, the results intended, a situation in which their application, their continuous application on a large scale, is possible.

Such a situation can exist only if socialists come to power, not as diffident agents of policies not their own, but as socialists, and, having done so, are prepared to deal with the opposition which they will encounter. They must have created behind them, before they assume office, a strong body of opinion, which" knows what it fights for, and loves what it knows." They must have measured coolly the forces which will be mobilised against them. The Labour Party has done neither. The reasons are partly historical. The British Labour movement was offered in its youth a foreign, and peculiarly arid, version of Marxian socialism. It very sensibly rejected it-very sensibly, not because the doctrine was Marxian, but because, in its pedantry and lack of historical realism, it was anything but Marxian. Then the unexpected happened. The seed sown by the pioneers began to bear fruit. The movement became a political power. Whole battalions were shepherded into it, much as the troops of Feng-husiang, "the Christian general," were baptised with a hose. Thanks to the judges, the unions were the first wave. The war brought another; the election of 1923 a third; the events of 1926 a fourth. By that time a generation had grown up to which it seemed as easy to be a socialist–as easy, if you please–as it had seemed difficult in 1900.

The result was that the British Labour Party, like British industry, was for a time too prosperous. It behaved, as the latter had behaved, as though summer would last forever. It had inherited from the nineteenth century the economic psychology of an age of expansion. In the flush of success, its political psychology assumed for a time the same florid complexion. It deceived itself both as to its own condition, and as to the character of the forces on its side and against it. It mistook luck for merit; treated votes, which were clearly indispensable, as equivalent to convictions, as to the practical value of which it was not equally certain; and drugged itself with the illusion that, by adding one to one, it would achieve the millennium, without the painful necessity of clarifying its mind, disciplining its appetites, and training for a tough wrestle with established power and property. It touched lightly on its objectives, or veiled them in the radiant ambiguity of the word socialism, which each hearer could interpret to his taste. So it ended by forgetting the reason for its existence. It has now to rediscover it.

Yet the objective of a socialist party, and of the Labour Party in so far as it deserves the name, is simplicity itself. The fundamental question, as always, is: Who is to be master? Is the reality behind the decorous drapery of political democracy to continue to be the economic power wielded by a few thousand-or, if that be preferred, a few hundred thousand-bankers, industrialists and landowners? Or shall a serious effort be made-as serious, for example, as was made, for other purposes, during the war-to create organs through which the nation can control, in co-operation with other nations, its own economic destinies; plan its business as it deems most conducive to the general well-being; over-ride, for the sake of economic efficiency, the obstruction of vested interests; and distribute the product of its labours in accordance with some generally recognised principles of justice? Capitalist parties presumably accept the first alternative. A socialist party chooses the second. The nature of its business is determined by its choice.

That business is not the passage of a series of reforms in the interests of different sections of the working classes. It is to abolish all advantages and disabilities which have their source, not in differences of personal quality, but in disparities of wealth, opportunity, social position and economic power. It is, in short-it is absurd that at this time of day the statement should be necessary-a classless society. It is not a question, of course, either of merely improving the distribution of wealth, or of merely increasing its production, but of doing both together. Naturally the methods required to attain that objective are various, complex and tedious. Naturally, those who accept it may do so for more than one reason-because they think it more conducive to economic deficiency than a capitalism which no longer, as in its prime, delivers the goods; or merely because they have an eccentric prejudice in favour of treating men as men; or, since the reasons are not necessarily inconsistent, for both reasons at once. In either case, they are socialists, though on matters of technique and procedure they may be uninstructed socialists. Those who do not accept it are not socialists, though they may be as wise as Solon and as virtuous as Aristides.

Socialism, thus defined, will be unpleasant, of course, to some persons professing it. Who promised them pleasure? The elements composing the Labour Party are extremely miscellaneous. If variety of educational experience and economic condition among its active supporters be the test, it is, whether fortunately or not, as a mere matter of fact, less of a class party than any other British party. That variety means that the bond of common experience is weaker than in parties whose members have been taught at school and college to hang together. Hence it makes the cohesion which springs from common intellectual convictions all the more indispensable. There is room for workers of all types in it, but on one condition. It is that, in their public capacity, they put their personal idiosyncrasies second, and their allegiance to the objectives of the party first. If they accept titles and such toys, without a dear duty to the movement to do so; or think that their main business is not fundamental reconstruction, but more money for the unemployed; or suppose that such reconstruction, instead of being specially urgent in the circumstances of today, must be kept in cold storage till the automatic occurrence of a hypothetical trade revival; or, like thirty-six Labour members in the last House of Commons, regard the defence of the interests, or fancied interests, of denominational schools as more important than to strike a small blow at class privilege 'in education, they may be virtuous individuals, but they are not socialists. To the Labour Party they are a source, not of strength, but of weakness. They widen the rift between its principles and its practice.

The programme of the party, again, covers a wide range. Nor need that be regretted, but, again, on one condition. It is that the different proposals contained in it should be rigorously subordinated to the main objective. Clearly, class-privilege takes more than one form. It is both economic and social. It rests on functionless property, on the control of key-positions in finance and industry, on educational inequalities, on the mere precariousness of proletarian existence, which prevents its victims looking before and after. Clearly, therefore, a movement seeking to end class-privilege must use more than one weapon; and clearly, also, the Labour Party's programme, like all socialist programmes, from the Communist Manifesto to the present day, must include measures which are secondary as well as measures which are primary. The essential thing is that it should discriminate between them. What will not do is that a programme should be built up by a process of half-unconscious log-rolling, this measure being offered to one section of workers, and that, because no one must be left in the cold, being promised to another.

The Labour Party can either be a political agent, pressing in Parliament the claims of different groups of wage-earners ; or it can be an instrument for the establishment of a socialist commonwealth, which alone, on its own principles, would meet those claims effectively, but would not meet them at once. What it cannot be is to be both at the same time in the same measure. It ought to tell its supporters that obvious truth. It ought to inform them that its business is to be the organ of a peaceful revolution, and that other interests must be subordinated to that primary duty. It is objected that, by taking that course, it will alienate many of them. It may, for the time being; New Models are not made by being all things to all men. But it will keep those worth keeping. And those retained will gather others, of a kind who will not turn back in the day of battle.

To formulate from time to time, amid swiftly changing complexities, international and domestic, a Labour policy which is relevant and up-to-date, is a task for the best brains that politics can command. But, when policy has been determined, two facts are as certain as political facts can be. The first is that, if a Labour Government, when it gets the opportunity, proceeds to act on it, it will encounter at once determined resistance. The second is that it will not overcome that resistance, unless it has explained its aims with complete openness and candour. It cannot avoid the struggle, except by compromising its principles; it must, therefore, prepare for it. In order to prepare for it, it must create in advance a temper and mentality of a kind to carry it through, not one crisis, but a series of crises, to which the Zinovieff letter and the Press campaign of last year will prove, it is to be expected, to have been mere skirmishes of outposts. Onions can be eaten leaf by leaf, but you cannot skin a live tiger paw by paw; vivisection is its trade, and it does the skinning first. If the Labour Party is to tackle its job with some hope of success, it must mobilise behind it a body of conviction as resolute and informed as the opposition in front of it.

To say this is not at all to lend countenance to a sterile propaganda of class hatred, or to forget that both duty and prudence require that necessary changes should be effected without a breakdown, or to ignore the truism that the possibility of effecting them is conditioned by international, as much as by domestic, factors. It is curious, in view of the historical origins of the Liberal movement, and, indeed, of such recent history as the campaign of 1909 against "the peers and their litter," that Liberals, of all people, should find a rock of offence in the class connections of the Labour Party. The reason for facing with candour the obvious and regrettable fact of the existence of a class struggle is not, of course, to idolise class, but to make it less of an idol than in England it is. It is to dissolve a morbid complex in the only way in which complexes can be dissolved, not by suppressing, but by admitting it. It is to emphasise that the dynamic of any living movement is to be found, not merely in interests, but in principles, which unite men whose personal interests may be poles asunder, and that, if principles are to exercise their appeal, they must be frankly stated. The form which the effort to apply them assumes necessarily varies, of course, from one society to another. Any realist view of the future of British socialism must obviously take account of the political maturity and dependence on a world economy of the people of Great Britain. It does not follow, however, that the struggle to be faced is less severe on that account. Intellectually and morally it may be more exacting.

If there is any country where the privileged classes are simpletons, it is certainly not England. The idea that tact and amiability in presenting the Labour Party's case-the " statesmanship " of the last Government--can hoodwink them into the belief that it is also theirs is as hopeful as an attempt to bluff a sharp solicitor out of a property of which he holds the title-deeds. The plutocracy consists of agreeable, astute, forcible, self-confident, and, when hard-pressed, unscrupulous people, who know pretty well which side their bread is buttered, and intend that the supply of butter shall not run short. They respect success, the man or movement that" brings it off." But they have, very properly, no use for cajolery, and laugh in their sleeves–and not always in their sleeves–at attempts to wheedle them. If their position is seriously threatened, they will use every piece on the board, political and economic-the House of Lords, the Crown, the Press, disaffection in the army, financial crises, international difficulties, and even, as newspaper attacks on the pound last summer showed, the emigre trick of injuring one's country to protect one's pocket-in the honest conviction that they are saving civilisation. The way to deal with them is not to pretend, as some Labour leaders do, that, because many of them are pleasant creatures, they can be talked into the belief that they want what the Labour movement wants, and differ only as to methods. It is, except for the necessary contacts of political warfare, to leave them alone till one can talk with effect, when less talking will be needed, and, in the meantime, to seize every opportunity of forcing a battle on fundamental questions. When they have been knocked out in a straight fight on a major economic issue, they will proceed, in the words of Walt Whitman, to "re-examine philosophies and religions." They will open their eyes and mend their manners. They will not do so before. Why should they ?

Part Three

If such are the objectives of the Labour Party, and such the forces against it, what are the practical conclusions ? They are four, relating respectively to programmes, propaganda, discipline, and tactics. The conclusion of an article is not the proper place for even the outline of a policy, which, with the world sliding as it is, may be out of date in six months. But certain points are clear. The business of making programmes by including in them an assortment of measures appealing to different sections of the movement must stop. The function of the party is not to offer the largest possible number of carrots to the largest possible number of donkeys. It is, while working for international peace and co-operation abroad, to carry through at home the large measures of economic and social reconstruction which, to the grave injury of the nation, have been too long postponed, and with that object to secure that the key-positions of the economic system are under public control. That task must, of course, be interpreted in a broad sense.

It is not for Labour to relapse into the Philistinism of the May Report, with its assumption that all but economic interests, and those interpreted a la capitalist, are of secondary importance. Side by side with action of a strictly economic character, such as the transference to public ownership of foundation services, including the banks; the establishment of machinery to bring the supply of capital to industry under public control; the creation of a permanent Industrial Development Commission to press steadily forward the modernisation of industrial organisation ; and such other measures of the same order as may be adopted, must go a policy for the improvement of education, health, and the system of local government, which themselves, it may be remarked, are matters not irrelevant to economic prosperity. It is monstrous that services vital to the welfare of the great majority of the population, and especially to that of the young, should be crippled or curtailed, while the rentier takes an actually larger percentage than in the past of the national income. If that income is too small to permit of our ensuring that all children have proper opportunities of health and education, it is clearly to') small to allow us other luxuries, including the continued payment of £300,000,000 odd a year to holders of war debt. A Labour Government should not wait till circumstances are favourable to a voluntary conversion, nor should it deal with war debt alone. It should follow the example set by Australia and other countries, and, indeed, as far as a disregard for the sanctity of contractual obligations is concerned, by the highly respectable Cabinet at present in power. It should compulsorily reduce fixed interest charges.

Of the general considerations which arise in planning a programme, the most important are three. The essentials must be put first, and sectional claims must not be permitted to conflict with them. The transference of economic power to public hands must take precedence over the mere alleviation of distress. It must be recognised that any serious attempt to give effect to such a policy will provoke a counter-attack, including action to cause economic embarrassment to the government of the day, and measures to meet it must be prepared in advance. The present government has shown that wealth can be redistributed, and existing contracts broken, by the convenient procedure of Orders in Council. The precedent should be remembered. An Emergency Powers Act is on the statute-book. Labour must be prepared to use it, and, if the powers which it confers are insufficient, to pass another.

What a Labour Government can do depends on what, when in opposition, it has taught its supporters to believe will be done. " Never office again without a majority " is the formula of the moment. But quality of support is as important as quantity. The Labour Party deceives itself, if it supposes that the mere achievement of a majority will enable it to carry out fundamental measures, unless it has previously created in the country the temper to stand behind it when the real struggle begins. Much of its propaganda appears to the writer-himself the least effective of propagandists-to ignore that truism. What is needed, is not merely the advocacy of particular measures of socialist reconstruction, indispensable though that is. It is the creation of a body of men and women who, whether trade unionists or intellectuals, put socialism first, and whose creed carries conviction, because they live in accordance with it.

The impressive feature of Russia is not that, apart from agriculture, the items in its policy are particularly novel. It is that, whether novel or not, they are being carried out. The force which causes them to be carried out is, not material, but spiritual. It is the presence of such a body, at once dynamic and antiseptic, the energumens, the zealots, the Puritans, the Jacobins, the religious order, the Communist Party-call it what you please-which possesses, not merely opinions, but convictions, and acts as it believes. Its existence does not depend on political forms; it is as compatible with Parliamentary, as with any other, machinery. Till something analogous to it develops in England, Labour will be plaintive, not formidable, and its business will not march.

The way to create it, and the way, when created, for it is to set about its task, is not to prophecy smooth things; support won by such methods is a reed shaken by every wind. It is not to encourage adherents to ask what they will get from a Labour Government, as though a campaign were a picnic, all beer and sunshine. It is to ask them what they will give. It is to make them understand that the return of a Labour Government is merely the first phase of a struggle the issue of which depends on themselves. It is objected that such methods involve surrendering for a decade the prospect of office. It may be replied that, if so, impotence out of office is preferable, at any rate, to impotence in it. It does not prejudice the future, or leave a record to be lived down. But is it certain that, had the late Government spoken in that sense before coming to power, and then fallen in 1930 in the attempt to carry a measure of first-class importance, it would have less likely to supply an alternative government in 1936? Talk is nauseous without practice. Who will believe that the Labour Party means business as long as some of its stalwarts sit up and beg for social sugar-plums, like poodles in a drawing room? On this matter there is at the moment a good deal of cant. The only test is the practical one; what behaviour is most conducive to getting on with the job ? A distinction may be drawn, no doubt, between compliance with public conventions and conduct in matters of purely personal choice. If one is a postman, one can wear a post-man's uniform, without thereby being turned into a pillar of sealing-wax. And, if Privy Councillors make up for the part, when duty requires it, by hiring official clothes from a theatrical costume-maker, who will let them for the day at not unreasonable rates, there is nothing to shed tears over, except their discomfort. The thing, all the same, though a trifle, is insincere and undignified. Livery and an independent mind go ill together. Labour has no need to imitate an etiquette. It can make its own.

It is one thing to bow down in the House of Rimmon, for practical reasons, when necessity requires it. It is quite another to press, all credulity and adoration, into the inner circle of his votaries. But the criticism on the snobbery of some pillars of the party, though just as far as it goes, does not go far enough. Those who live in glass houses should not throw stones. The truth is that, though the ways of some of the big fish are bad, those of some of the smaller fry are not much better. Five-pounders and fingerlings, we insist on rising, and-shades of Walton!-to what flies!

It will not do. To kick over an idol, you must first get off your knees. To say that snobbery is inevitable in the Labour Party, because all Englishmen are snobs, is to throw up the sponge. Either the Labour Party means to end the tyranny of money, or it does not. If it does, it must not fawn on the owners and symbols of money. If there are members of it-a small minority no doubt, but one would be too many-who angle for notice in the capitalist press ; accept, or even beg for, "honours"; are flattered by invitations from fashionable hostesses ; suppose that their financial betters are endowed with intellects more dazzling and characters more sublime than those of common men ; and succumb to convivial sociabilities, like Red Indians to fire-water, they have mistaken their vocation. They would be happier as footmen. It may be answered, of course, that it is sufficient to leave them to the ridicule of the world which they are so anxious to enter, and which may be trusted in time–its favourites change pretty quickly-to let them know what it thinks of them. But, in the meantime, there are such places as colliery villages and cotton towns. How can followers be Ironsides if leaders are flunkies?

One cannot legislate for sycophancy; one can only expose it, and hope that one's acquaintances will expose it in oneself. The silly business of " honours" is a different story. For Labour knighthoods and the- rest of it (except when, as in the case of civil servants and municipal officers, such as mayors and town clerks, they are recognised steps in an official career) there 1s no excuse. Cruel boys tie tin cans to the tails of dogs; but even a mad dog does not tie a can to its own tail. Why on earth should a Labour member ? He has already all the honour a man wants in the respect of his own people. He can afford to tell the tempter to take his wares to a market which will pay for them and himself to the devil. While the House of Lords lasts, the party must have spokesmen in it. Peerages, therefore, have very properly been undergone, as an unpleasant duty, by men who disliked them. It should in future, be made clear, beyond possibility of doubt, that that reason, and no other, is the ground for accepting them. When it is necessary that a Labour peer should be made, the victim required to play the part of Jephtha's daughter should be designated by a formal vote of the Parliamentary Party meeting. It is not actually essential that the next Annual Conference should pass a resolution of sympathy with him and his wife, but it would be a graceful act for it to do so. What odious Puritanism! Yes, but the Puritans, though unpleasant people, had one trifling merit. They did the job, or, at any rate, their job. Is the Labour Party doing it?

If there is the right spirit in the movement, there will not be any question of the next Labour Government repeating the policy of office at all costs which was followed by the last. Whether it takes office without an independent majority is a matter of secondary importance compared with its conduct when it gets there. Its proper course is clear. The only sound policy for a minority government is to act like a majority government. It is not to attempt to enact the less controversial parts of its programme; for its opponents give nothing away, and will resist a small measure of educational reform as remorselessly as a bill for the nationalisation of the land. It is to fight on large issues, and to fight at once. It is to introduce in the first three months, while its prestige is high and its moral unimpaired, the measures of economic reconstruction which it regards as essential. It will, of course, be defeated if it is in a minority, in the Commons, if it is in a majority, in the Lords. In the second case, it can use the Parliament Act, supposing it to be still law, and go to the country on the abolition of the House of Lords; in the first, it must demand a dissolution. In either, it will do better for the nation and itself by forcing the issue, than by earning as its epitaph the answer which Sieyes gave: to the question what he had done during the Terror: "j'ai vecu": "I kept alive."

It is objected that such a policy involves sacrificing opportunities for useful work, particularly in the field of international affairs. It may-for the time being; had the late government acted on it, Sir John Simon would have succeeded Mr. Henderson after one year, instead of after two. On a long view, however, the dilemma is less absolute than that argument suggests. The League is what the rulers of the Great Powers, and the interests behind them, permit it to be. In the light of the history of the last thirteen years, and not least of 1931-32-in the light, for example, of their attitude in the test case of Manchuria and of the tragic farce of the Disarmament Conference–can it seriously be argued that they are eager that it should itself be a power, or that even a Labour Government, if it holds office at the mercy of its opponents and the League's, can succeed, during a brief spell of precarious authority, in making it one? It is obvious that, as the world is to-day, no nation can save itself by itself; we must co-operate, or decline. But is it probable that international co-operation can be built on a foundation of states dominated, in their internal lives, by ideals antithetic to it? Those who cannot practise their creed under their own roof can practice it nowhere, and one contribution, at least, which a Labour Government can make to that cause is to be made at home. It is to apply to the affairs of its own country the principles which, it believes, should govern those of the world. It is to extend the area of economic life controlled by some rational conception of the common good, not by a scramble, whether of persons, classes, or nations, for individual power and profit.

Sir Arthur Salter, in contrasting the frank individualism of the nineteenth century with the improvised, half-conscious experiments in collective control of the post-war world, observes that " we have, in our present intermediate position between these two systems, lost many of the advantages of both, and failed to secure the full benefits of either." In the sphere of international, as of domestic, policy, the attempt to give a social bias to capitalism, while leaving it master of the house, appears to have failed. If capitalism is to be our future, then capitalists, who believe in it, are most likely to make it work, though at the moment they seem to have some difficulty in doing so. The Labour Party will serve the world best, not by doing half-heartedly what they do with conviction, but by clarifying its own principles and acting in accordance with them.

This article was originally published in The Political Quarterly in July 1932.

Need help using Wiley? Click here for help using Wiley