| 4 mins read

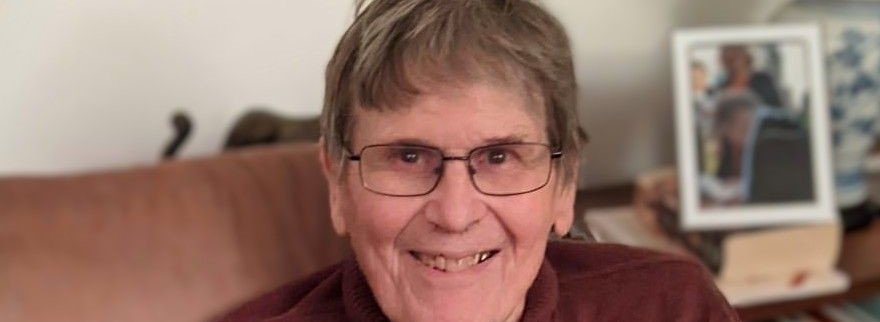

With the death of David Marquand in his 90th year the Political Quarterly circle has lost, not just a fine, politically wise academic mind, but a great human being and the warmest of friends.

At first sight his life was a straightforward example of the progressive wing of the British establishment. His father had been a Labour MP; David had been educated at Oxford. He was himself Member of Parliament for Ashfield from 1966-77; chef du cabinet to Roy Jenkins when the latter was president of the European Commission. Then came the academic achievements: a notable historian, with several well regarded books to his credit; successive chairs at the universities of Salford and Sheffield; the principalship of Mansfield College, Oxford; fellowship of the British Academy.

But look behind all that and you see someone who never took the easy route. Although an historian who wrote brilliantly in the classic English tradition of political biography, he fully understood and valued the very different field of political economy. At Sheffield he set up the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI), which flourishes today. Mansfield is a rather special Oxford College, devoted to exploring new fields of work in human rights and similar fields. David left the Labour Party in the early 1980s to become one of the founders of the short-lived Social Democratic Party. This was an unorthodox thing to do. To join a new breakaway party in Britain is almost always a politically suicidal act, and he knew that. His politics was neither careerist nor tribalist. He believed in certain values, and he would support or leave a party depending on how it related to those values. He therefore returned to Labour when it moved back from the far-left positions of the 1980s; and left it again to join Plaid Cymru during the Corbyn years.

To understand his sometimes surprising trajectory one needs only to read some of his books: The Unprincipled Society (1988), The New Reckoning (1997) and Mammon’s Kingdom (2013). These not only present a searing criticism of neoliberalism and what it has done to Britain, but make that criticism from a deeply moral position. He might have written about grand figures and themes, but his heart was in the struggles of ordinary people and the small communities they need in order to live fulfilling lives. That made him an opponent of top-down Toryism, amoral neoliberalism and centralizing socialism alike. He was a dedicated Europeanist, but needed that to be coupled to the values of smallness – values that he exemplified personally in his deep capacity for warm good humour, friendship and hospitality.

His political and personal qualities were well captured by the remarks of two people who knew him well, when the sad news of his death reached them. Will Hutton: ‘His mapping of the need for, and obstacles to, a marriage of ethical socialism and progressive liberalism was surely right’. And Jean Seaton: ‘He was an establishment contrarian. Besides being jolly clever and thoughtful (which as we all know are different) he somehow combined a sweetness and generosity of person with a kind of gloomy Eeyore-ish eye on public life...the Ramsey MacDonald biography perhaps key.’

As a tribute, the Political Quarterly collection Progressive Dilemmas: A Virtual Issue in Honour of David Marquand is available to read in its entirety for free until the end of May.