| 5 mins read

Imagine, for a second, a radical right voter; someone, perhaps from UKIP or AfD, or even the National Rally (formerly National Front). The image coming to mind is likely a middle aged, or older, working class man, with strong conservative attitudes on a variety of issues, from immigration and the European Union, to women’s rights and the environment.

This image is fairly accurate, yet only tells part of the story. If I draw a radical right voter at random, there’s only about a 25 per cent chance he, or she, would conform to this expectation. Many, surprisingly, actually have somewhat liberal positions.

My recent journal article examines the attitudinal and demographic breakdown of the West European radical right from 2004 to 2016, with the European Social Survey, a biennial survey of European public opinion. Using a statistical technique that places individuals into groups based on similar survey responses and demographic characteristics, I find three broad types of radical right voters – conservative, moderate, and sexually-modern nativists.

The “conservative nativists”, as I alluded to above, comprise about a quarter of my sample. These individuals are older, less educated, and are more likely to be men. They prefer traditional family structures and strong government, and are highly opposed to immigration and European integration. This is the typical “radical right voter”.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the “sexually-modern nativists”. About a third fall into this group. As indicated by the “nativist” label, these voters are only slightly less nationalist than the conservatives. However, in other regards, they look like leftists – they’re younger, highly educated, more likely to be women, and are not opposed to gender egalitarianism and LGBT rights. The third group falls in between these two extremes, taking more moderate positions.

Increase in ‘sexually modern’ nativists

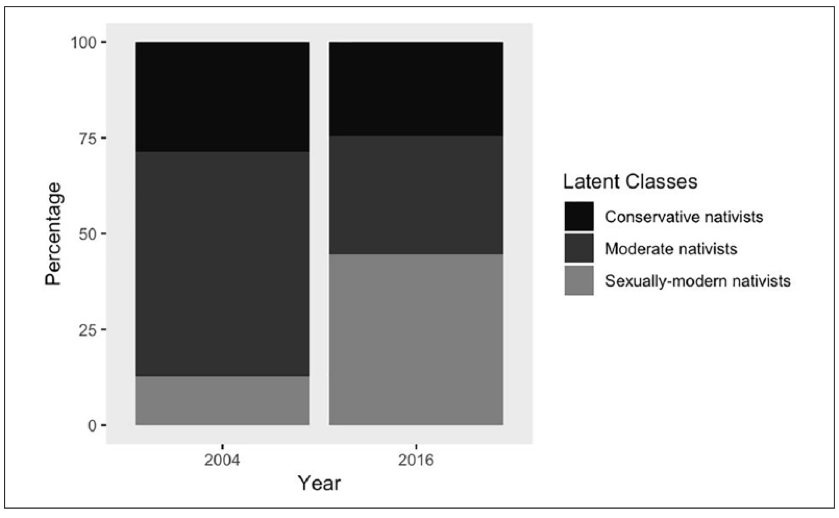

The most striking result from my analyses concerns the extent to which the “sexually-modern” group in Europe has increased in prevalence overtime. In 2004, the vast majority of the radical right is either moderate or conservative; only 12 per cent are sexually-modern. However, in 2016, almost half – 45 per cent – fall into this category.

Indeed, there is variation across the 10 countries in my study; Austria and Switzerland have more conservative radical right voters, while other countries, like the Netherlands and Sweden, are less conservative, but the general trend remains.

Yet why do we observe less conservatism among today’s radical right? From Germany and France to Sweden and Denmark, radical right parties now discuss women’s and LGBT rights as fundamental to Europe’s identity – and I argue that party rhetoric and the shock of the Syrian refugee crisis are key factors.

This “liberal nationalist” rhetoric was popularized in the Netherlands in the early 2000s by the late Pim Fortuyn, an openly gay sociology professor who founded a radical right party just months before the 2002 Dutch general election. Fortuyn provided a decidedly different rationale for restricting Muslim immigration. It was not that immigration caused job loss or terrorism, as other radical right leaders have claimed. Rather, he considered Islamic culture to be “backwards”, an existential threat to the rights of women and the LGBT community.

This new framing of the immigration issue spread and paved the way for the populist resurgence of the mid-2010s. Spurred by the Syrian refugee crisis, immigration became an issue of unprecedented urgency and concern for European publics. And the radical right, long considered the most authoritative party family on this issue, was standing by to benefit. “Liberal nationalist” rhetoric made the radical right seem more accessible and less taboo to new voters who, in the past, may have never considered such an extreme option. Yet with refugees arriving on the shores of Europe in shocking numbers, and a European Union unsure of solutions, many voters, perhaps, saw no other alternative.

No longer can we dismiss the radical right as the party family of angry old men, reacting against a changing society. Now, women and gay men are likely to be found within their ranks, alongside voters who, if not for their immigration attitudes, might be confused for leftists. With support for populists at an all-time high, it is crucial that we understand who exactly these parties attract, and why.