| 13 mins read

In this ongoing catalogue of coronavirus-related disorder – extraordinary death tallies, a global lockdown and chaotic financial markets – history reminds us that it is in precisely these conditions that old doctrines are overturned and new paradigms are ushered in.

Crises catapult changes. Amidst this pandemic there are now mass protests across America following the death of George Floyd, an African American, at the hands of a white police officer. The tear gas and ‘show of force’ tactics deployed by the US police on protesters mark a new inflection point in this crisis, highlighting its perils and possibilities.

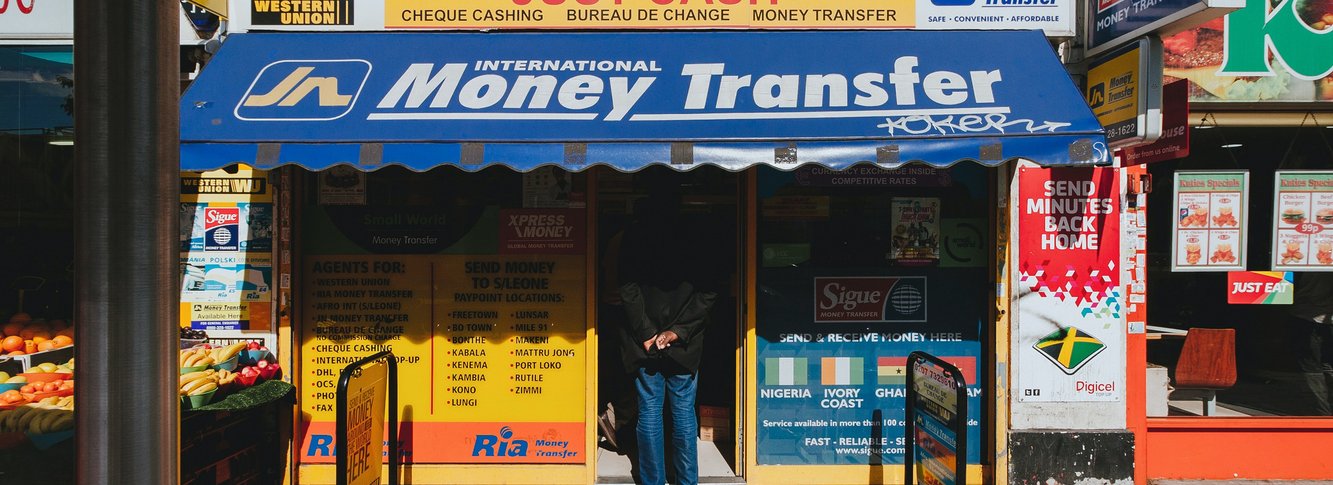

This moment, if any, clarifies and crystallises the necessity of a new social contract. Whilst economic thinking might appear distant and removed from more immediate concerns, unequal access to finance and other forms of social provisioning has amplified the suffering of marginalised communities across the world.

Now is the time to conceive and construct a new international monetary system, different to the present which furthers the political and economic dominance of a few to one founded on principles of social justice and sustainability. Lessons learned from the past might guide us as we reimagine global money for the twenty-first century.

Bretton Woods and beyond

In mid-century Britain, the Keynesian revolution was catalysed by total war and the active state interventionism it necessitated. Aggregate demand management was adopted in the 1941 budget. The Beveridge Report of 1942 laid the basis for postwar Britain’s welfare state. By 1944, British economic policy had, on paper, committed to full employment.

It was in this context that the conference at Bretton Woods to stake claims over postwar international economic governance convened in 1944. Whilst cultivating an aura of multilateralism, it was primarily Anglo-American negotiations, spearheaded by John Maynard Keynes and the US Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White, that determined Bretton Woods’ outcome.

Roundly ignored was India – more specifically, its pleas for a greater voting share at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and enquiries about when its $1.25 billion balances would be returned to the subcontinent.

US and UK interventions during coronavirus

The highest number of reported deaths from Covid-19 thus far have been in the US and the UK. In both nations, people of color and BAME groups, who are also disproportionately represented amongst the ranks of ‘essential workers’, have been particularly hard-hit, both by the pandemic and the aftershock of economic crisis. In the UK, according to ONS statistics, Blacks people are four times as likely to die from Covid-19 compared to others.

Initially, both Trump and Johnson betrayed remarkable hubris and indifference in the face of scientists warnings about the oncoming pandemic. However, once the virus rattled financial markets, UK and US central bank intervention has been swift, innovative, and unprecedented in scale and scope. The Federal Reserve Bank balance sheet alone tops $7 trillion and is expected to expand to $10 trillion by the end of this year.

Financial contagion in the global south

In the global south, deprived of the monetary autonomy and fiscal capacity enjoyed by these world financial powers, liquidity is drying up when it is most needed. An unprecedented $100 billion in portfolio funds exited emerging markets since the onset of this crisis. Low-income countries do not yet account for the highest number of deaths from Covid-19 although contagion rates are rising. They have, however, been struck by a financial contagion whose magnitude, even in these early days, appears the most immense in living memory.

As investors flee into ‘safe haven’ assets, especially those denominated in dollars, emerging markets have been thrown into a deflationary-debt spiral of currency devaluations, mushrooming external liabilities, and sovereign debt downgrades. The outstanding volume of foreign-currency debt owed by emerging economies is $5.3 trillion, of which $730 billion matures this year. More than eighty percent of this is dollar-denominated. Roughly sixty percent of low and middle income country public sector foreign currency debt is owed to private-sector entities and almost half of outstanding foreign debt is through bond issuance – in short, much riskier than own-currency denominated bank loans.

Debt servicing exceeds health budgets by fourfold on average in 46 low-income economies. The majority of developing economies are heavily dependent on their commodity export revenues. These have fallen by 37 per cent this year. The UN World Food Programme reports that for poorer parts of the global economy, particularly formerly colonised nations now ensnared in conflict, famines of biblical proportion are on the horizon. Severe coronavirus outbreaks could cripple these nations; Nigeria’s former finance minister has said that some African countries have fewer than 100 ventilators.

SDR: The IMF’s powerful tool

At the social-distancing-enforced IMF spring meetings, chief economist Gita Gopinath urged that international assistance be made “timely,” “larger,” and “more unconditional.” Bear in mind that 23 of the 26 IMF loans approved in 2016 and 2017 were conditional on borrowers enforcing fiscal consolidation – in other words, austerity.

The IMF’s maximum lending capacity is less than $1 trillion, far short of the $2 - $3.5 trillion that UNCTAD estimates is required by developing countries to navigate this crisis. While G20 central bankers have agreed to suspend debt servicing payments for the poorest nations and the IMF has approved about $230 million in new debt relief for 27countries, these actions are a drop in the ocean.

But the IMF has in its own kitchen a very powerful monetary tool: the Special Drawing Right (SDR). Created in 1969 with unanimous approval from all IMF members (Americans acquiescing under French pressure), the SDR was a late borne and much diluted version of Keynes’ bancor, a new synthetic world currency, that been nixed in favor of the dollar at Bretton Woods.

The 2008 global financial crisis propelled its use as an international means of payment between central banks following a $250 billion new SDR issuance in 2009. Distributed according to country quotas at the IMF, several low-income countries made use of their SDRs converting them into cash or using them to pay off their IMF loans.

This time around, commensurate to the enormity of the crisis, SDR issuance should be ten times as much compared to 2009, in line with UNCTAD’s estimate. Steve Mnuchin, the US Treasury Secretary, can vote for a US SDR allocation of $650 billion without congressional approval. These SDRs could be quickly donated to countries in need. Other rich countries could follow suit: donating or lending (interest rates for borrowing SDRs are very low) their SDR allocations.

Compared to the dollar share in global foreign reserves (60 per cent), the SDR share is miniscule (less than 3 per cent). Expanding the use of the SDR beyond payments between central banks would require changes in the IMF’s Articles of Agreement. Permitting that, as country deposits at the IMF they could be used in low-cost, high-yield international financial assistance such as hard currency-SDR swaps. These financial arrangements between poor and low-income countries and rich-country donors could be facilitated by the IMF.

Additional aid and programmatic support could be provided by the World Bank and regional financial institutions such as the African Development Bank andthe Asian Development Bank. The IMF’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, recently called for “greening the recovery”. The IMF could stipulate that programs financed through SDRs be directed towards sustainable publicinfrastructure along with addressing the more immediate needs in the ‘care economy’ (public health and social services).

Despite many calls for a one-off special SDR issuance for all IMF member countries – which requires US approval given its large vote share at the IMF – American reluctance has foreclosed that possibility for now. Reportedly, the reason is because SDRs would de facto be issued to China and Iran.

The biggest impediment, then, is not finance. The limits of dollar liquidity are essentially inflationary expectations which are far off the horizon. Instead, the impediment is political. Yet this crisis, the worst shockwave that the modern world economy has ever encountered, is precisely the time in which the US could reap manifold benefits from benevolent global leadership.

The future of public banking

Central banks and international financial institutions are not removed from the ‘care economy’: by creating and managing liquidity they have an essential role to play in social provisioning. In the twenty-first century, public banking must be driven not by doctrinaire austerity and conditionalities which disproportionately impact poorer households and countries but by inclusivity and interconnectedness, as embodied in the UN’s sustainable development goals.

In his teleconference with reporters at the end of April, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank,Jerome Powell, articulated the very sort of empathic response now required towards Black, Latinx, and low-income workers whose unemployment rates have been rising faster than others. This was remarkable for any central banker, let alone the world’s most powerful one. But empathy does not redress centuries of exclusionary policies. The crisis has dismantled the myth that monetary policies are independent of fiscal policies. Taxation, employment, and housing policies, for instance, must shrug off their purportedly ‘neutral’ stance which by default mostly benefit rich white households to actively embrace race- and class-conscious goals.

Internationally, G20 central bankers have called for suspending debt servicing for the poorest countries. However additional actions should be taken, such as temporarily banning private creditors from suing indebted sovereign states in New York and London, the world’s financial and legal capitals, and preventing firms receiving public money from engaging in stock buybacks and dividend payouts.

Capital controls

Recognising the macroeconomic instability generated by short-term financial flows and keenly aware that the burden of monetary management should not fall on indebted nations alone, both Keynes and White’s original plans explicitly advocated that countries experiencing significant capital flight and, equally important, countries to where capital was fleeing, enforce capital controls.

Unfortunately, in the final IMF Articles of Agreement, such controls had been undermined. The British economist Joan Robinson charged that Article VI left the US “free from any inducement to control capital transfers” except in the event of the unusual “scarce currency” clause. This failure to stanch ‘hot money’ led to a deluge of dollars offshore into London’s Euromarkets, ultimately destroying the Bretton Woods monetary system from within. It is that same broken institutional architecture that allows capital flight to roil developing economies and marginalised communities today.

A new international monetary system is badly needed. One lesson from studying the late nineteenth and early twentieth century sterling standard or the post-second world war world dollar standard is that global dominance and currency power are inextricably linked. In a democratic vision of twenty-first century economic governance, however, one in which planetary viability matters more than power or profits, world money must be made a global public good and precarity properly relegated to the past.